Preventing Work-related Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever)

Summary Statement

This California Department of Public Health factsheet describes the very real risks of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis). When the top 2 to 12 inches of dry soil is disturbed by digging, vehicles or the wind, the fungal spores get into the air and can be inhaled. The flu-like symptoms are generally mild in 60% of the cases, but moderate to severe in 40%. In about 5% of the cases, the disease spreads and workers can die from the infection.

This factsheet contains suggestions for preventing and controlling exposures.

June 2013

Valley Fever is an illness that usually affects the lungs. It is caused by the fungus Coccidioides immitis that lives in soil in many parts of California. When soil containing the fungus is disturbed by digging, vehicles, or by the wind, the fungal spores get into the air. When people breathe the spores into their lungs, they may get Valley Fever.

Is Valley Fever a serious concern in California? YES!

Often people can be infected and not have any symptoms. In some cases, however, a serious illness can develop which can cause a previously healthy individual to miss work, have longlasting and disabling health problems, or even result in death.

This fact sheet describes actions employers can take to prevent workers from getting Valley Fever and to respond appropriately if an employee does become ill.

In October 2007, a construction crew excavated a trench for a new water pipe. Within three weeks, 10 of 12 crew members developed coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever), an illness with pneumonia and flu-like symptoms. Seven of the 10 had abnormal chest x-rays, four had rashes, and one had an infection that had spread beyond his lungs and affected his skin. Over the next few months, the 10 ill crew members missed at least 1660 hours of work and two workers were on disability for at least five months.

How do workers get Valley Fever?

In California, Valley Fever is caused by the fungus Coccidioides immitis that lives in the top two to 12 inches of soil in many parts of the state. When soil containing this fungus is disturbed by activities such as digging, vehicles, or by the wind, the fungal spores get into the air. When people breathe the spores into their lungs, they may get Valley Fever. Fungal spores are small particles that can grow and reproduce in the body. The illness is not spread from one person to another.

How do employers know if the fungus is present in soil at their worksites?

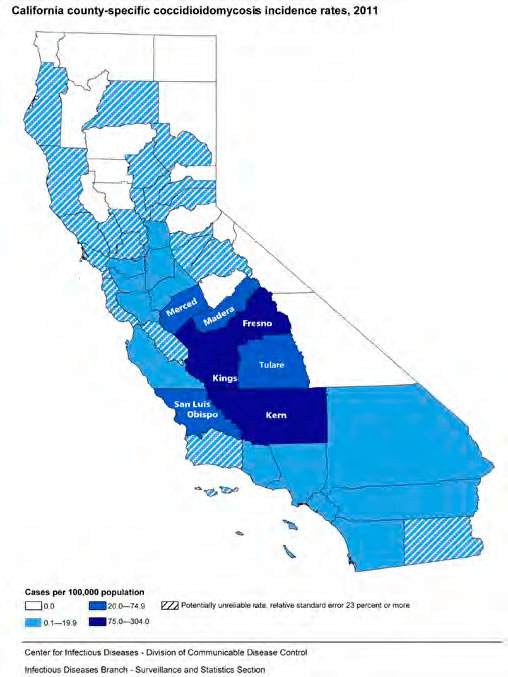

The Valley Fever fungal spores are too small to be seen by the naked eye, and there is no reliable way to test the soil for spores before working in a particular place. Some California counties consistently have the Valley Fever fungus present in the soil. In these regions Valley Fever is considered endemic. Health departments track the number of cases of Valley Fever illness that occur. This information is used to map illness rates as seen on the figure above. Employers can contact their local health department for more information about the risk in their counties.

Where do people get Valley Fever?

Highly endemic counties, i.e., those with the highest rates of Valley Fever (more than 20 cases per 100,000 population per year), are Fresno, Kern, Kings, Madera, Merced, San Luis Obispo, and Tulare. Other counties or parts of counties also have the fungus present.

California county-specific coccidioidomycosis incidence rates, 2011

Who is at risk for Valley Fever?

Workers who disturb the soil by digging, operating earth-moving equipment, driving vehicles, or working in dusty, wind-blown areas are more likely to breathe in spores and become infected. Some occupations at higher risk for Valley Fever include:

- Construction workers, including roadbuilding and excavation crews

- Archeologists

- Geologists

- Wildland firefighters

- Military personnel

- Workers in mining, quarrying, gas and oil extraction jobs

- Agricultural workers*

* Cultivated, irrigated soil may be less likely to contain the fungus compared to undisturbed soils.

Anyone, even healthy young people, can get Valley Fever. Once a person has had Valley Fever, their body may develop some immunity against future infections.

How does Valley Fever affect health?

- Experiments on laboratory animals indicate that a very small dose, 10 spores or fewer, may cause an infection.

- After breathing in the spores, the following can happen:

- In about 60% of cases, symptoms are mild or not present.

- In about 40% of cases, symptoms vary from moderate to severe. Usually symptoms are those of a flu-like illness that may last up to a month but goes away on its own. However, some people develop pneumonia (at times severe).

- In a small proportion of cases (about 5%), disease spreads outside of the lungs causing very serious illness. Parts of the body that may be affected include the brain (meningitis), bones, joints, skin, or other organs. This is called disseminated Valley Fever (or disseminated coccidioidomycosis).

- People who are more likely to have severe or disseminated Valley Fever include those who have weakened immune systems, such as people who are HIV positive, have AIDS, cancer, or diabetes; who smoke; or who are pregnant. People of African and Filipino descent are much more likely to get disseminated disease; however, others can get disseminated disease, too.

Earth-moving equipment may stir up spores

What are signs or symptoms of Valley Fever?

When present, symptoms usually occur between seven to 21 days after breathing in spores, and can include:

- Cough

- Fever

- Chest pain

- Headache

- Muscle aches

- Rash on upper trunk or extremities

- Joint pain in the knees or ankles

- Fatigue.

Symptoms of Valley Fever can be mistaken for other diseases such as the flu (influenza) and TB (tuberculosis), so it is important for workers to obtain medical care for an accurate diagnosis and possible treatment.

Disseminated Valley Fever

Dissemination refers to spread of infection beyond the lungs to other parts of the body. With Valley Fever this usually occurs within the first six to 12 months after the initial illness.

Signs or symptoms of disseminated Valley Fever may vary but usually consist of some combination of the following:

- Fever

- Raised skin lesions with irregular surfaces

- Lymph node swelling, especially in the neck

- Pain and swelling in one or more joints

- Recurrent, persistent, new headaches (may be mild)

- Stiff neck.

Preventing Valley Fever exposure

There is no vaccine to prevent Valley Fever. Employers can reduce worker exposure by incorporating the following elements into the company’s Injury and Illness Prevention Program and project-specific health and safety plans:

- Determine if the worksite is in an area where Valley Fever is endemic (consistently present). Check with your local health department to determine whether cases have been known to occur in the proximity of your work area. See the map on page 2 to determine whether your company will be working in an endemic county.

- Train workers and supervisors on the location of Valley Fever endemic areas, how to recognize symptoms of illness (see page 3), and ways to minimize exposure. Encourage workers to report respiratory symptoms that last more than a week to a crew leader, foreman, or supervisor.

- Limit workers’ exposure to outdoor dust in disease-endemic areas. For example, suspend work during heavy wind or dust storms and minimize amount of soil disturbed.

- When soil will be disturbed by heavy equipment or vehicles, wet the soil before disturbing it and continuously wet it while digging to keep dust levels down.

- Heavy equipment, trucks, and other vehicles generate heavy dust. Provide vehicles with enclosed, air-conditioned cabs and make sure workers keep the windows closed. Heavy equipment cabs should be equipped with high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters. Two-way radios can be used for communication so that the windows can remain closed but allow communication with other workers.

- Consult the local Air Pollution Control District regarding effective measures to control dust during construction. Measures may include seeding and using soil binders or paving and laying building pads as soon as possible after grading.

- When digging a trench or fire line or performing other soil-disturbing tasks, position workers upwind when possible.

- Place overnight camps, especially sleeping quarters and dining halls, away from sources of dust such as roadways.

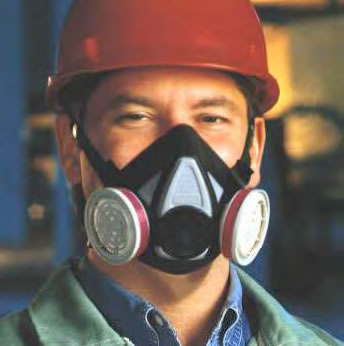

- When exposure to dust is unavoidable, provide NIOSH-approved respiratory protection with particulate filters rated as N95, N99, N100, P100, or HEPA. Household materials such as washcloths, bandanas, and handkerchiefs do not protect workers from breathing in dust and spores.

Respirators for employees must be used within a Cal/OSHA compliant respiratory protection program that covers all respirator wearers and includes medical clearance to wear a respirator, fit testing, training, and procedures for cleaning and maintaining respirators.

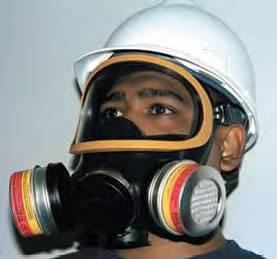

Different classes of respirators provide different levels of protection according to their Assigned Protection Factor (APF) (see table below). Powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) have a battery-powered blower that pulls air in through filters to clean it before delivering it to the wearer’s breathing zone. PAPRs will provide a high level of worker protection, with an APF of 25 or 1000 depending on the model. When PAPRs are not available, provide a well-fitted NIOSH-approved full-face or half-mask respirator with particulate filters.

Fit-tested half-mask or filtering facepiece respirators are expected to reduce exposure by 90% (still allowing about 10% faceseal leakage), which can result in an unacceptable risk of infection when digging where Valley Fever spores are present.

PAPR with helmet (APF=1000)

Full-face respirator (APF=50)

Half-mask respirator (APF=10)

The table below shows the relative effectiveness of various types of respirators for particles of dust and spores.

| Respiratory Protection for Reducing Dust and Spore Exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Respirator Type (worn with particulate filters) | Assigned Protection Factor (APF) | Expected Reduction of Exposure to Dust and Spores (%) | |

|

No respirator | None | 0 |

| Half-mask respirator (elastomeric or filtering facepiece) | 10 | 90 | |

| Powered air-purifying respirator with loose-fitting face covering | 25 | 96 | |

| Full-face respirator | 50 | 98 | |

| Some powered air-purifying respirators are designed to offer higher protection (check with manufacturer) | 1000 | 99.9 | |

Preventing transport of spores

- Clean tools, equipment, and vehicles with water to remove soil before transporting offsite so that any spores present won’t be re-suspended in air and inhaled at a later time.

- Provide workers with coveralls or disposable Tyvek™ daily. At the end of the work day, require workers to remove their work clothes at the worksite.

- Keep street clothes and work clothes separate by providing separate lockers or other storage areas. If possible, store work boots at the worksite; otherwise, have workers use a boot wash before getting into their vehicles.

- Encourage workers to shower and wash their hair at the workplace (if at a fixed location) or as soon as they get home.

What should employers do if a worker reports Valley Fever symptoms?

- If the worker disturbed soil or otherwise did dusty work in an endemic area, the employer should send the worker to their workers’ compensation health care provider or occupational medicine clinic. The employer should provide the health care provider with the details about the dust or soil exposure. The worker should give a copy of this fact sheet to the health care provider.

- When two or more workers report symptoms that suggest Valley Fever, workers should be sent to a single medical provider or occupational medicine clinic for coordinated medical care, if possible. This can facilitate better communication between the medical provider, public health agencies, and employer.

- Travel through endemic areas has resulted in Valley Fever cases. When a worker who has traveled through an endemic area reports a respiratory illness that lasts more than a week, the employer should send the worker to their workers’ compensation health care provider or occupational medicine clinic.

- Complete the “Employer’s Report of Occupational Injury or Illness” (Form 5020) for each occupational Valley Fever illness which results in “lost time” or medical treatment beyond first aid.

- List cases on the Cal/OSHA Form 300, “Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses”.

- Report immediately any serious injury, illness or death occurring in a place of employment or in connection with any employment to the local Cal/OSHA district office. A “serious injury or illness” is defined in 8 CCR 330(h) found at www.dir.ca.gov/title8/330.html.

What is the treatment for Valley Fever?

Although many people with Valley Fever do not require treatment, those with symptoms should seek medical attention. When Valley Fever is suspected, doctors can order specialized tests to confirm the diagnosis. If treatment is indicated, anti-fungal medications are available. Workers who develop severe or chronic infections may need to stay in the hospital.

It is especially important for people at risk for severe disease, such as people infected with HIV or those with weakened immune systems, to be diagnosed and receive treatment as quickly as possible. People with severe infections need to be treated because advanced Valley Fever can be fatal.

Summary of Controls to Minimize Workers’ Dust Exposure and Risk of Valley Fever in Endemic Areas

Type of Control: Engineering and Work Practice Controls (to control dust at the source or isolate worker from exposure.)

Actions: Minimize exposure to outdoor dust:

- Suspend (stop) work in dust storms or high winds.

- Minimize the amount of digging by hand. Instead, use heavy equipment with operator in an enclosed, airconditioned, HEPA-filtered cab.

Continuously wet the soil before and while digging or moving the earth. Landing zones for helicopters and areas where bulldozers, graders, or skid steers operate are examples where wetting the soil is necessary.

When digging in soil is required, train workers to reduce the amount of dust inhaled by staying upwind when possible.

Type of Control: Administrative Controls (to increase hazard awareness and knowledge of safe work practices and select safer work practices.)

Actions: Train workers and supervisors on:

- Distribution of endemic areas

- Symptoms and signs, and need to report to supervisor to obtain medical evaluation

- People at highest risk of serious disease

- Effective controls, including proper use of equipment.

Type of Control: Personal Protective Equipment (to decrease quantity of fungal spores inhaled.)

Actions: Provide respirators when digging or working near earthmoving trucks or equipment:

- Powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) with high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter or

- Full-face respirator with particulate filter or

- Half-mask respirator with particulate filter and

- Implement a comprehensive respirator program including medical clearance, training, fit testing, and procedures for cleaning and maintaining respirators.

Provide coveralls to prevent street clothes from being contaminated with fungal spores and then taken home.

Type of Control: Clean up (to decrease quantity of fungal spores inhaled.)

Actions: Provide lockers and require change of clothing and shoes at worksite so workers don’t take dust and spores home.

Wash equipment before moving offsite.

Type of Control: Medical care for disease recognition and prompt, appropriate treatment.

Actions: Contract with local medical clinics

- Provide prompt evaluation and care

- Make sure clinic has a protocol for evaluation, follow-up, and treatment of Valley Fever

Make sure in-house physician is aware of work in Valley Fever endemic areas.

Valley Fever in the general population in California (includes individuals exposed at work)

- In 2011, 5123 people were diagnosed with new infections.

- The number of new Valley Fever cases reported in California increased dramatically in the past few years. In 2011, there were 20% more cases compared to 2010.

- Every year, about 1,430 people are hospitalized with Valley Fever.

- About 8% (8 out of 100) of people hospitalized with Valley Fever die due to the infection.

Resources

For more information:

- California Department of Public Health, “Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Fact Sheet” www.cdph.ca.gov/healthinfo/discond/pages/coccidioidomycosis.aspx Available in English, Spanish, and Tagalog. Also see Yearly Summary Report of Coccidioidomycosis in California.

- California Department of Public Health, Hazard Evaluation System and Information Service (HESIS). HESIS answers questions about workplace hazards for California workers, employers, and health care professionals. Call (510) 620-5817 or (866) 282-5516 (toll free in CA). HESIS has many free publications available. To request publications, leave a message at (510) 620-5717 or toll free (866) 627-1586, or visit our website at www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/ohb

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,“Coccidioidomycosis, Valley Fever” http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Increase in Reported Coccidioidomycosis-United States, 1998-2011,” March 29, 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6212a1.htm

- Injury and Illness Prevention Program. This standard (California Code of Regulations (CCR) Title 8, Section 3203), requires employers to implement an injury and illness prevention program (IIPP). For links to publications on IIPPs, see www.dir.ca.gov/title8/3203.html.

- Respiratory Protection. This standard, CCR Title 8, Section 5144, requires employers to provide respirators when necessary to protect the health of employees. See www.dir.ca.gov/title8/5144.html.

To obtain a copy of this document in an alternate format, please contact: (510) 620-5757. (CA Relay Service: 800-735-2929 or 711). Please allow at least ten (10) working days to coordinate alternate format services.

HAZARD EVALUATION SYSTEM & INFORMATION SERVICE

California Department of Public Health, Occupational Health Branch

850 Marina Bay Parkway, Building P, 3rd Floor,

Richmond, CA 94804

510-620-5757

www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/ohb

Edmund G. Brown Jr., Governor

State of California

Diana S. Dooley, Secretary

Health and Human Services Agency

Ron Chapman, MD, MPH, Director and

State Health Officer

California Department of Public Health

Marty Morgenstern, Secretary

Labor and Workforce Development Agency

Christine Baker, Director

Department of Industrial Relations