Summary Statement

Newspaper article about the dangers of pressure treated wood and stories about arsenic-based illnesses that resulted from working with it.

Rick Feutz still remembers how the sawdust caked his body.

The Seattle science

teacher was building a wooden float for his children. The experience would

change his life.

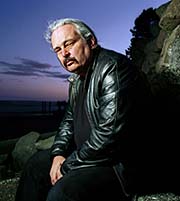

Rick Feutz shown here on the beach near his Poulsbo, Wash., home, suffers some facial paralysis and lack of strength in his fingers because of a reaction to working with treated wood in 1986 |

For more than a week, Feutz cut pressure-treated wood with a power saw. After a few days, he felt like he was getting the flu. After a few more days, he collapsed while pushing a wheelbarrow.

For a year, Feutz couldn't walk without a walker and was so disoriented in the dark he had to crawl.

Fifteen years later, the former Washington Teacher of the Year still suffers from weakness, memory loss and partial paralysis in his face - lingering effects from what doctors said was severe arsenic poisoning.

The arsenic was in the wood.

Pressure-treated lumber contains a potent chemical called CCA, which stands for chromium, copper and arsenic. Chromium and arsenic are heavy metals known to cause cancer. They are also among the most toxic substances for people and animals.

Most people who buy the wood don't know that.

Thousands use it every day, to build billions of board feet of decks, fences, porches and picnic tables. The chemical wards off insects and prevents fungus. Most consumers don't get a warning about it.

In recent weeks, statewide media attention has focused on the use of CCA-treated wood at playgrounds. Arsenic in the wood is leaching into the soil, and authorities are fencing off playgrounds until they figure out whether the levels are safe.

Last week, workers began removing playground equipment at the Baby Gator child care center on the University of Florida campus. With kids, the wood is just too risky, university health officials said.

But as Feutz's case makes clear, the wood can be riskier for people who work with it.

"When I think of it now, I think of that fine sawdust all over my body, brushing it off," said Feutz, now 53 and an executive for a company that makes computer keyboards. "I didn't think anything of it."

And why would he?

Like most people, Feutz didn't know the wood was filled with pesticide. He didn't know he was supposed to wear a dust mask when he sawed it. He never got the warning sheet the industry promised it would give to consumers.

He didn't know a single board contains enough arsenic to kill 80 people or make hundreds very sick.

He didn't know sawdust could hurt so bad.

Feutz might not be the only one who found out too late.

A Gainesville Sun investigation found more than 40 incidents nationwide where a person blamed CCA-treated wood for illness or injury. At least a dozen of those incidents were supported by a doctor's testimony or toxicology reports. In two cases, a jury agreed the chemical was at fault.

There is no comprehensive government registry of cases or problems involving pressure-treated wood. The Sun found these incidents in court records, medical journals and government files obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

Many incidents involved sawing. Some involved burning or splinters. Some involved merely handling the wood.

Together, the incidents suggest that carpenters, construction workers and do-it-yourself consumers who work with the wood all the time may be facing an unanticipated threat to their health.

Kids not No. 1 problem

In the past year, CCA has come under intense scrutiny in Florida.

Environmental officials are worried about arsenic leaching into groundwater. Parents are worried about arsenic at playgrounds.

In the past two weeks, authorities in Florida have closed parts of at least a half-dozen playgrounds because high arsenic levels were found in the soil. Last year, the Kidspace playground at Terwilliger Elementary School in Gainesville was torn down for the same reason.

Meanwhile, a lawsuit filed in federal court in Miami this month charged the $4 billion-a-year treated-wood industry with hiding the dangers of CCA.

Suddenly, everyone wants to know if their kid's playground is a hazardous waste site.

Most toxicologists say there's no cause for alarm. They say the chances are extremely slim that a child might be poisoned or get cancer from playing on CCA-treated wood, or even from eating the arsenic-laced dirt beneath it.

The industry has said that all along.

After a yearlong search, The Sun found only one incident involving CCA and children. And it involved exposure from burning CCA wood in a stove - not from climbing on a pressure-treated play set.

The incidents reviewed by The Sun suggest the biggest threat from CCA isn't on the playgrounds.

It's at the garages, workshops and construction sites where people saw or sand the wood, and in other places where they might burn or mishandle it.

Among the incidents:

- A New York man swelled up and stopped breathing while he was making a deck.

- An Indiana man vomited several pints of blood after making picnic tables.

- An Alabama man got a splinter that caused his hand to swell up like a lobster claw.

- A California man got a headache that lasted five days after boring holes in the wood.

- A Florida man lost two prize race horses after they ate CCA-treated fencing.

- A Wisconsin family suffered seizures, blackouts and massive hair loss after burning it.

William Croft, a retired environmental toxicology professor at the University of Wisconsin, diagnosed the Wisconsin family and determined they were poisoned by arsenic in the wood.

Pressure-treated wood is "really dangerous," Croft said. "The public has no idea."

But if the wood is so bad, wouldn't more people report getting sick?

"I don't believe it," said Harold McCann, a Levy County man who was buying pressure-treated wood at Lowe's in Gainesville last week.

"I use the chips and sawdust in my garden," said McCann's neighbor, Pat Reagan.

To be sure, thousands of people use pressure-treated wood every day and do not get sick.

Toxicologists say some people are more sensitive to toxins than others.

Some people might have gotten a heavier dose of arsenic because of special circumstances, such as prolonged sawing in an unventilated room. Some people might have exposed themselves, but not at levels that led to noticeable effects.

Critics of CCA say some people might have gotten sick and never suspected the wood.

Why would they suspect it, they ask, if they don't know what's in it?

Some specialists who track worker safety issues see a threat. They say they are convinced carpenters and construction workers have been put at increased risk of certain types of cancer because of chronic exposure to low levels of arsenic from CCA.

Because CCA didn't become widely used until the 1970s, they say those effects wouldn't show up until now. No government studies are under way to measure whether they have.

The wood industry says there is no proof the wood ever hurt anybody.

It says sawdust from CCA wood is no worse than sawdust from chemical-free wood.

Last week, Home Depot in Gainesville posted information sheets near every stack of CCA lumber that say the wood is no more toxic than "ordinary table salt." The sheets were made by Osmose Wood Preserving Inc., a leading manufacturer of CCA.

There are no documented cases where "a doctor said, 'This is the cause, this is the effect,' " said Huck DeVenzio, a spokesman for Arch Wood Protection, formerly Hickson Inc., another leading maker of CCA.

As for some of the cases found by The Sun, DeVenzio said he never heard of them and couldn't comment.

Popular product

CCA is everywhere.

Ranchers use it for fences. Utility companies use it for power poles. Government agencies use it for bus stops and boardwalks.

Do-it-yourselfers use it the most. For barriers to set off gardens. For decks to barbecue on. For picnic tables and swing sets.

Look around: All that wood with the greenish tint? That's CCA.

For the wood industry, CCA is a miracle product. It extends the life of cut Southern pine from a few years to a few decades. The arsenic wards off termites. The copper stops fungus. The chromium helps it bind to the wood.

Without CCA, the industry says 225 million more trees would be cut down every year to replace rotting wood.

Environmental officials overseas have not been persuaded. Switzerland, Vietnam and Indonesia have banned CCA-treated wood. Japan, Germany and a handful of other countries have put tough restrictions on its use.

In the United States, CCA-treated wood is one of the anchors of the billion-dollar home-improvement industry. Every day, thousands of people load it up at Lowe's, Home Depot, Scotty's and other lumber retailers.

It's so popular, it even transcends college football rivalries. UF coach Steve Spurrier and Florida State Seminoles coach Bobby Bowden both pitch Osmose treated lumber in TV commercials.

Dangerous substances

But some people are seeing those decks and play sets in a new light.

Both arsenic and chromium are on the government's Top 20 list of hazardous substances. Arsenic is No. 1.

There is some debate about whether the chromium found in pressure-treated wood is in a form that can be harmful.

The wood is treated with a solution that includes hexavalent chromium. That's the toxin in the film "Erin Brockovich," which was based on the real-life story of a scrappy law clerk who links a town's medical problems to pollution in drinking water.

The industry says once the chromium binds to the wood, it reverts to a less harmful form. But some CCA critics, such as Indiana attorney David MacRae, who has filed several lawsuits against the industry, point to studies that suggest not all of it converts.

There is no debate about the arsenic. Toxicologists agree it's in a form that can hurt.

In pure form, it takes only a pinch of arsenic - a fraction of the amount in a sugar packet - to kill a person. It takes even less to make a person very sick.

The question is: Can enough be released in sawdust - and then inhaled, or ingested, or absorbed through the skin - to hurt somebody?

Mel Pine, spokesman for the American Wood Preservers Institute, said the makers of CCA haven't even studied the possibility because it's "so remote."

Some doctors and toxicologists say otherwise.

In either case, The Sun found little coordination between government health and safety agencies to study and track any problems.

"We're all aware of the possibility," said Selene Chou, an environmental health scientist with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and a leading arsenic expert. "The pathway is there. The chemical is there."

But the studies are not. Agencies that evaluate the risks of consumer products and dangers in the workplace haven't assessed the risks of CCA. They say they haven't received any complaints. The Sun found them at another agency.

For a 1990 report, the US Consumer Products Safety Commission determined the long-term cancer risk to children playing on pressure-treated wood. It concluded the risk was remote.

But the commission never studied the risk to consumers from splinters or toxic sawdust.

The commission frequently issues warnings or recalls on products. Often, it takes only the possibility of an injury to prompt such action - as in 1996, when the agency recalled stuffed animals with detachable plastic eyes that might choke a child.

But in this case, the commission would "probably yield to EPA," agency spokesman Ken Giles said.

EPA files show at least a dozen cases where people blamed their ailments - headaches, rashes, shot nerves - on CCA-treated wood.

It is unclear whether any of them had medical documentation. To protect their privacy, the EPA blacked out their names, phone numbers and addresses before releasing the reports.

In one complaint, a Melbourne Beach man told the EPA in 1997 that for three years, he sawed CCA wood at a construction site.

He suspected that sawdust and fumes from a hot saw ruined the nerves in his legs and feet. He said doctors in Jacksonville and Gainesville told him he was just getting old, but another doctor found high levels of arsenic in his hair.

"At no time were we told about the dangers involved with the use of CCA-treated lumber," the man wrote. "I hope to find out if anyone is responsible for not telling us."

Day in court denied

If researchers ever do launch a study, they might include Russell Sirico.

Sirico thought "pressure-treated" meant the wood had been pressurized to be more compact, stronger. He didn't know pressure-treated wood had been bathed in a giant cylinder full of chemicals and injected - at high pressure - with arsenic and chromium.

"It's not 'chemical treated.' It's not 'pesticide treated.' It's pressure treated," said Sirico, a US Postal Service employee who lives 50 miles north of New York City. "I had no idea it was dangerous."

In the summer of 1989, Sirico, now 42, set out to build a deck. It was hot. He didn't wear a shirt. He sawed and hammered at the wood all day for days.

"I was getting the sawdust on my skin. I was smoking cigarettes. I was eating, drinking," he said. "I sucked it in every way you can probably think of."

After a week, Sirico was weak and breaking out in rashes. After two weeks, his face, arms and legs "swelled up like a balloon." He collapsed at work and was taken to the hospital. The next day, he had a severe asthma attack, something he never had before.

For a few moments, he stopped breathing.

Doctors who treated Sirico concluded his "life threatening" reaction was because of chemicals in the wood, court records show.

Sirico filed suit against the lumber company and CCA makers in 1990 but would never get his day in court.

A judge ruled the defendants followed federal law in putting a warning label on the chemical that was shipped to the treatment plant.

Sirico complained that he had never been warned. The wood itself did not have a warning on it.

The decision was upheld.

A doctor hired by the treated-wood industry said there was no proof Sirico was poisoned by CCA.

Even if he was, the doctor said, his reaction was so "highly unusual and idiosyncratic" the industry couldn't be liable.

Sick after sawing

But other people have fallen sick after sawing pressure-treated wood.

In Washington state, county parks worker Robert Clement got sick building bridges in '78 and '79.

He was sawing a type of pressure-treated wood related to CCA that also contains arsenic. He became weak. His muscles atrophied. Lesions formed on his hands and feet. A neurologist said in a court deposition he had arsenic poisoning.

Clement sued the companies that treated and supplied the wood. A jury awarded him $450,000.

In Indiana, US Forest Service worker James Sipes got sick building picnic tables in 1983 and 1984.

Sipes vomited blood on two separate occasions. His coworker also got sick. Tests done on their hair and nails showed arsenic levels that were hundreds of times above normal. After the second incident, Sipes did not return to work.

Sipes and his coworker sued lumber stores, wood treaters and CCA makers. They settled with all but one company for $667,000. After a trial, a jury told the holdout to pay $100,000.

In Missouri, state parks worker Randy Wadlow got sick building CCA walkways in 1986 and 1987.

For a year, he sawed it, stacked it and breathed in fumes created by welding near it. He said he got weaker and weaker, but didn't want to complain. Finally, he coughed up blood and had to be hospitalized. He never returned to work.

A doctor told Wadlow he had "toxic pneumonia."

"I got to the point where I thought I was going to die," Wadlow said. "I never did feel any better. Burnt my sinuses up."

Industry insiders have known about problems, potentially caused by the chemical, for decades.

In an interoffice memo obtained in a liability case involving CCA, former industry scientist Robert Arsenault lists three incidents he said may have been caused by "CCA dust toxicity."

At the time, Arsenault worked for Koppers, a company that has since become part of Arch Wood Protection.

In one incident, college students in a research lab got sick from sanding the wood and inhaling the dust.

In the second, a man machining and planing CCA-treated poles for a week "went home sick with respiratory illness, coughing and general ill health," the memo said.

In the third, workmen building wood foundations began "coughing up blood and had developed a skin rash."

Arsenault said in all three cases, the workers recuperated.

The scientist's memo was written in 1977.

Voluntary warnings

The EPA once wanted warnings. Mandatory warnings.

In 1978, the agency undertook an official review of all types of wood preservatives, including CCA.

It was concerned that chemicals in the wood were hurting people and the environment. In the early 1980s, it decided there was enough of a threat that warning sheets should be given to every customer who buys CCA-treated wood.

The industry and the EPA don't call those notices "warning sheets." They call them "consumer information sheets."

But the sheets tell people there is arsenic in the wood, that exposure can be hazardous and that a long list of precautions should be taken before working with it.

Among the instructions: Wear gloves. Wear goggles. Wear a dust mask.

And don't burn it because "toxic chemicals may be produced as part of the smoke and ashes."

The industry fought a mandatory warning.

It suggested a voluntary program and promised the EPA that consumers would get information sheets. In 1985, after battling the industry for seven years, the EPA said OK.

Greg Kidd, legal policy director for the anti-pesticide group Beyond Pesticides, speculated the industry fought mandatory warnings because telling buyers up front about toxins in the wood would have been "business suicide."

Several industry representatives said they didn't know why the industry fought for a voluntary program.

But they agreed it is not working.

State officials have complained to the EPA about the program for years.

In 1993, the South Dakota Department of Agriculture surveyed lumber retailers in that state to find how many were handing out consumer information sheets. The survey was ordered after a child was found playing with pieces of CCA wood and sawdust.

The survey found

fewer than one in 10 lumber stores were handing out sheets at the point

of sale - which is what the EPA wanted and the industry promised. South

Dakota officials forwarded their findings to the EPA, but nothing changed.

Gainesville carpenter Joseph Saccocci has worked with CCA-treated lumber for five years. JOHN MORAN/The Gainesville Sun |

"I never got one," Gainesville carpenter Joseph Saccocci said.

Saccocci said he thought the term "treated wood" meant it had been doused with water repellent.

Carpenters "don't think of this as chemical," said Saccocci, working on a deck in northwest Gainesville. "We think of this as wood."

Saccocci said he has never taken any special precautions with the wood. He said he doesn't know many carpenters who have.

The lawsuit filed in Miami two weeks ago called the industry's consumer awareness program a "farce."

The EPA is now reviewing CCA to determine if it will be reregistered as a pesticide. As part of the review, the agency is pulling out incident reports and catching up on the latest research about CCA.

It also is considering, again, whether to make the information sheets mandatory.

Root of illness missed

When James Sipes, the Indiana man who got sick making picnic tables, first started feeling bad, his doctor told him he had sinusitis.

The next day he vomited several pints of blood. The emergency room doctor told him to go on a mild diet and take Tagamet, an over-the-counter heartburn drug.

"He said, 'Just go home and you'll get over it,' " Sipes said.

It took Sipes months to recover. A year later, he started sawing CCA-treated wood again to make more picnic tables. After three weeks in the workshop, he vomited blood again.

This time, Sipes diagnosed himself. He realized it might be the wood. He found out from his boss that the wood had chromium, copper and arsenic in it, then had his hair and nails tested. Sure enough, the tests showed high levels of arsenic.

What happened to Sipes is no surprise to people who track the effects of pesticides and toxic hazards in the workplace.

Most people don't consider whether a chemical might be at the root of their sickness, said Ken Halperin, an injury prevention manager with CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training, an arm of the AFL-CIO labor union.

And neither do doctors, he said.

They "never think to ask what chemicals you worked with," Halperin said. "They're not trained that way."

Halperin said he is convinced pressure-treated wood is a health threat for carpenters and construction workers - a still-hidden danger like asbestos was for maintenance workers.

Croft, the Wisconsin toxicologist, said the Wisconsin family sought medical attention from more than 60 doctors before he found a link to the wood they were burning.

Only a handful of states require doctors who suspect pesticide exposure to report those cases to a tracking system.

And in some of those states, compliance rates are pitifully low. Florida health officials say few doctors follow the reporting rules here.

The EPA tracking system relies on the pesticide maker. If the company gets a call about an exposure incident, it's supposed to file a report.

No call, no report.

Forced to settle

Rick Feutz's recovery has been long and slow.

He still tires easily. His memory is spotty. He can't always close his mouth when he chews.

On the bright side, he said, he has learned to drink from a soda can again: "I use my tongue as a bottom lip."

Feutz sued the lumber store, the wood treater and the CCA makers. In the end, he settled.

The amount could not be disclosed because of a confidentiality agreement, but Feutz's attorney said it was "substantial."

Feutz said he feels guilty about settling. He said a trial would have raised awareness about CCA. He said it might have kept other people from getting hurt like he did.

But medical bills were mounting. He had a wife and three young children to think about.

At Lowe's in Gainesville last week, Byron Bush and two other construction workers were loading slats of CCA lumber into a pickup truck. They planned to saw them up at a construction site. They do it all the time.

"I never heard of a problem with it," Bush said. His coworkers shook their heads, too.

A few miles away, Saccocci, the carpenter, tore through planks of pressure-treated wood with a circular saw.

No gloves. No dust mask. Just like most people do it.

"You asked me if we get sawdust on us," Saccocci said, smiling.

The blade whined. The wood gave. A cloud of sawdust poured from the side of the saw.

In a few minutes, sawdust was everywhere.

Ron Matus can be reached at (352) 374-5087 or ron.matus@gainesvillesun.com.