Bending Toward Justice: How Latino Immigrants Became Community and Safety Leaders

Summary Statement

This report is from a CPWR-financed collaboration of a New Jersey-based workers’ center called New Labor, researchers at Rutgers University, and immigrant workers themselves. The research team used a community-based participatory approach to identify and build on the aspirations and abilities of day laborers. Through these efforts, the day laborers embraced workplace safety and health as a fundamental human right and became leaders who have facilitated classes for more than a thousand of their peers. They also provided safety demonstrations on street corners and in parking lots to many hundreds of day laborers seeking construction work, and testified before OSHA during 2014 public hearings. They have mentored coworkers, prepared new trainers and have shared their knowledge and skills with other worker centers around the country.

2014

“…the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.”

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Keep Moving From This Mountain sermon, 1965

“ Latino immigrants ARE vulnerable workers—but they are so much more than that.… Our goal is to help workers build on their inherent strengths, including their motivations to create a better life and their desire to help themselves and others.”

— Michele Ochsner, Rutgers University, 2014

"In my country, I know how to navigate the system – but not here. That’s why I come to New Labor.

When I came here, I learned from New Labor that I have value and that has made (a huge) difference. It helped me to learn, more importantly that all of us have the same rights. … I learned we have the right to safety at the worksite and that employers have the obligation and responsibility to provide us with a safe environment and proper equipment."

This is the story of immigrant Latino construction workers: how they were organized through a community worker center, New Labor, embraced workplace safety and health as a fundamental human right, and became leaders by collaborating with universitybased health and safety researchers. New Labor’s worker leaders have facilitated classes for more than a thousand of their peers, provided safety demonstrations on street corners and in parking lots to many hundreds of day laborers seeking construction work, and testified before OSHA during 2014 public hearings. They have mentored coworkers, prepared new trainers and have shared their knowledge and skills with other worker centers around the country. And as both research subjects and peer researchers, these immigrants who became worker leaders have provided important insights into conditions on residential construction sites and the world view of those who seek to make their living in this high-risk industry.

This is the story of immigrant Latino construction workers: how they were organized through a community worker center, New Labor, embraced workplace safety and health as a fundamental human right, and became leaders by collaborating with universitybased health and safety researchers. New Labor’s worker leaders have facilitated classes for more than a thousand of their peers, provided safety demonstrations on street corners and in parking lots to many hundreds of day laborers seeking construction work, and testified before OSHA during 2014 public hearings. They have mentored coworkers, prepared new trainers and have shared their knowledge and skills with other worker centers around the country. And as both research subjects and peer researchers, these immigrants who became worker leaders have provided important insights into conditions on residential construction sites and the world view of those who seek to make their living in this high-risk industry.

How did Latino immigrants, new to this country with little command of English working long hours in dangerous jobs, become trainers in classrooms and on street corners, then research partners, mentors, experts delivering presentations, and community leaders? It happened through a unique collaboration among the New Jersey-based workers’ center, New Labor, researchers at Rutgers University, and the workers themselves. Funded through CPWR - The Center for Construction Research and Training, the research team used a community-based participatory approach to identify and build on the aspirations and abilities of day laborers.

The story starts with the workers – and the issues they faced:

- I came for economic reasons, for my family. I have 7 kids, all the money I make is for them.… I haven’t seen them since 2005.

- I worked in agriculture more than anything else…. I also worked in a clothing factory for 6 years … the economic situation wasn’t that good.

- Until I was 33, I was a farmworker. I suffered a lot trying to make ends meet.

- I was trained as a barber and was politically active against the [Honduran] government.

Although international agreements help trade to cross borders freely, they also displace workers in industries unable to compete in global markets. Immigrant workers are pushed by factors in their home countries – high unemployment, low wages, crime, war, persecution, family responsibilities – but are pulled into the U.S. by one thing: jobs. Over the past 20 years, much of the increase in the U.S. workforce has been due to immigration, slowed only by the great recession.1

A dangerous trade

One worker fell and hurt his hip. He complained to the boss, who said everyone gets hurt and everyone works. The owner made a lot of money.

My cousin was hurt very badly – his face was cut with a circular saw when the blade fell off and hit him. The boss pushed him to use the blade for steel when he was cutting a wood.

Construction provides many jobs to immigrant Latino workers. They often choose to be a day laborer in construction as a higher paid alternative to agriculture or low-wage factory or service jobs. Often marginalized and unsure of their rights, street corner day laborers live outside of the formal work sector, working for small contractors, subcontractors and home owners seeking cheap labor. Despite the potential to earn higher wages, workers often encounter wage theft, discrimination, disabling injuries or worse. And “worst” happens too frequently, as documented when BLS Program Manager Scott Richardson presented his data analysis of worker fatalities at the 2010 National Action Summit for Latino Worker Health & Safety. He found foreign-born workers die at rates 50% higher than workers born in the U.S.2

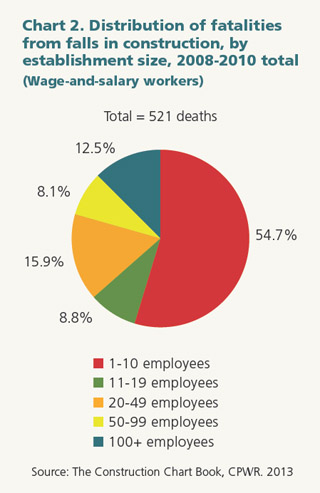

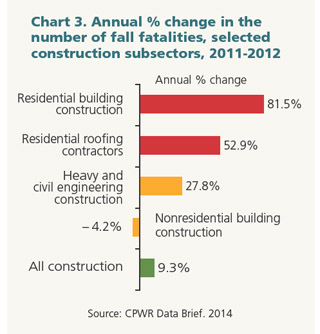

Construction work kills more workers than any other industry in the United States (see Chart 1).3 Construction contractors with less than 10 employees hold the terrible distinction of having 55% of all construction fatalities from falls. Nearly 80% of all fatal falls happen to contractors with less than 50 employees (see Chart 2).4 From 2011 – 2012, the number of fatal falls in residential construction jumped by nearly 82%; fatal falls among residential roofing contractors rose by 53% (see Chart 3).5

Construction work kills more workers than any other industry in the United States (see Chart 1).3 Construction contractors with less than 10 employees hold the terrible distinction of having 55% of all construction fatalities from falls. Nearly 80% of all fatal falls happen to contractors with less than 50 employees (see Chart 2).4 From 2011 – 2012, the number of fatal falls in residential construction jumped by nearly 82%; fatal falls among residential roofing contractors rose by 53% (see Chart 3).5

I had a workplace accident, and realized I didn’t understand my rights. I cut the tendon in my hand. The contractor took me to the hospital and told me to say it happened at home and he was just my friend.… He told me they wouldn’t treat me if they knew I was an undocumented immigrant.… I needed to get back to work.

The employer knows he is supposed to provide the equipment, but if you ask [for equipment to protect you], they drive away, not pay you, and you have to get back on your own.

Using knowledge to inform action

Community-based worker centers have developed throughout the U.S. in response to the basic needs and concerns of immigrant workers. New Labor, a worker center with offices in New Brunswick, Lakewood and Newark, was founded in 2000 as an alternative model of worker organization using the guiding principles of “Working Together, Creating Opportunities, Respect, Empowerment, and Equality.” Initially, New Labor focused on English language education, computer skills development, and wage theft, although occupational health and safety quickly emerged as an important focus. As conditions in low-wage labor markets have worsened, New Labor has turned its attention to leadership development and direct actions that include negotiating with employers individually, public demonstrations and active engagement with government agencies to address health and safety along with wage and hour violations and recovery of lost wages. During an recent 18-month period, New Labor helped workers recover more than $250,000 in lost wages.

With New Labor, we know that we have the backing of an organization. We know where to go to learn more about our rights.

Virtually all workers coming to New Labor knew someone who had been seriously injured on the job or had experienced injuries themselves. Economically desperate workers frequently accept jobs they know are unsafe to survive and send money home to their families. Few knew about OSHA or that safety and health regulations applied – regardless of immigration status – and most feared government in all forms. They worry about everything from falls to chemical exposures, but they often feel they don’t have a choice. Almost none of them understood how job hazards could be prevented.

Virtually all workers coming to New Labor knew someone who had been seriously injured on the job or had experienced injuries themselves. Economically desperate workers frequently accept jobs they know are unsafe to survive and send money home to their families. Few knew about OSHA or that safety and health regulations applied – regardless of immigration status – and most feared government in all forms. They worry about everything from falls to chemical exposures, but they often feel they don’t have a choice. Almost none of them understood how job hazards could be prevented.

In 2004, New Labor began to work with Rutgers University health and safety researchers to address these issues with a five-year grant from the national non-profit, CPWR – The Center for Construction Research and Training. CPWR is funded through a cooperative agreement with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), CDC, and serves as NIOSH’s National Construction Center.

Based on extensive focus groups and pilot trainings with Latino construction laborers,6 Rutgers labor educator Carmen Martino worked with New Labor’s executive director, Lou Kimmel, to adapt the 10-hour OSHA Hazard Recognition Training for Construction program, already available to unions through the Building and Construction Trades Department, AFL-CIO, SmartMark training materials. Martino and Kimmel developed 14 relevant, hands-on, participatory modules focused on hazardous situations relevant to day laborers. With trainings supervised by participating OSHA-authorized trainers, the classes were designed to be delivered by trained peer educators coached in participatory methods.

One of the ways we have been very effective is by learning about workers’ rights and sharing that information. [We’re] also effective in taking care of each other – making sure co-workers don’t get hurt.

I told the guys that if they cut concrete they should ask for the right equipment. But some of them aren’t willing to do it. Also I told them, “Don’t say you can do something if you really don’t know how to do it.”

How it all happened

Networking with day laborers at street corners that served as mustering or hiring sites across New Jersey, New Labor staff honed in on six communities with large numbers of immigrant workers in construction and recruited workers with an interest in health and safety – plus the willingness and ability to facilitate training with a written health and safety curriculum. These workers became the peer trainers who would also assume leadership roles within New Labor. During the initial five years of the project, New Labor peer trainers worked with staff to recruit workers from street corners and construction jobs and reached out to small contractors, eventually teaching one-day classes to a total of 425 workers. Training participants learned about ladder safety, scaffold safety, personal protective equipment, electrical safety, trench hazards, dust hazards and more.

Street corner and parking lot demonstrations are a first step to connect with day laborers who are eager to learn safe work practices.

At the beginning you are faced with the workbook, you don’t understand, but people who have been through before, help you. People who can’t read learn from others in the group.

There is a person who withdraws because he doesn’t know how to read or write, but we try to pull him back in. He listens carefully and expresses his opinions. At the beginning everyone feels a little excluded–we don’t know each other … now, we will exchange phone numbers and addresses.

The training was anything but dry. The program focused heavily on lived experience, small group discussion, problem-solving, and use of a wide variety of resources, including a frank discussion of the risks faced by Latino workers in an activity called “Job Fear.” Safety and health on the job came clearly into focus as a basic human right. Conversations about those who had lost everything – workers maimed or killed on the job – placed the nature of the risks in perspective. By comparing experiences and sharing strategies, these workers encouraged each other to speak out and reach out. Participants practiced negotiating or brainstorming solutions, and worked through information to demystify OSHA and highlight the rights available to all workers and ways to access them. Workers’ experiences were validated, and they practiced “speaking up.” Researchers demonstrated that the training made a difference: a comparison of surveys conducted before and several months after the training demonstrated a statistically significant increase in using PPE and self-protective actions.7 Trainees also reported referring back to training materials and sharing insights with co-workers. When they were asked about how often they had used the safety training workbook and other materials, 83% reported they had referred to the New Labor Health and Safety workbook at least once, and 61% referred back to the workbook a few times or more. Similar results were also found with regard to laborers dispensing workbook information to their friends and co-workers: 80% shared workbook information at least once and 66% shared information a few times or more. Peer trainers enjoyed learning from each other in small groups and enthusiastically shared knowledge with others.

The training was anything but dry. The program focused heavily on lived experience, small group discussion, problem-solving, and use of a wide variety of resources, including a frank discussion of the risks faced by Latino workers in an activity called “Job Fear.” Safety and health on the job came clearly into focus as a basic human right. Conversations about those who had lost everything – workers maimed or killed on the job – placed the nature of the risks in perspective. By comparing experiences and sharing strategies, these workers encouraged each other to speak out and reach out. Participants practiced negotiating or brainstorming solutions, and worked through information to demystify OSHA and highlight the rights available to all workers and ways to access them. Workers’ experiences were validated, and they practiced “speaking up.” Researchers demonstrated that the training made a difference: a comparison of surveys conducted before and several months after the training demonstrated a statistically significant increase in using PPE and self-protective actions.7 Trainees also reported referring back to training materials and sharing insights with co-workers. When they were asked about how often they had used the safety training workbook and other materials, 83% reported they had referred to the New Labor Health and Safety workbook at least once, and 61% referred back to the workbook a few times or more. Similar results were also found with regard to laborers dispensing workbook information to their friends and co-workers: 80% shared workbook information at least once and 66% shared information a few times or more. Peer trainers enjoyed learning from each other in small groups and enthusiastically shared knowledge with others.

What I have noticed is that they are teaching us to be leaders at the corner.… It is very good, because you learn to respect other persons’ opinions and points of view and have respect for yourself as a worker.

Training takes root

One employer was worried I would complain – he fired me. One employer was interested – I got a hard hat and mask. … this particular employer wanted me to help … [and to] convince co-workers to wear PPE.

Interactive training, like correct use of

equipment, is the basis of this program.

Workers hit the books, too.Yesterday I saw workers doing dry cutting and not using masks. I told the worker that he needs a mask, and he understood and went out to get a mask and glasses and then his co-worker rigged a “wet saw” by pouring water while he cut. They were Filipino and spoke Spanish so they understood.

From my point of view, this training has been great. You need to learn more – no reason to be isolated. I decided to become a trainer to learn … but also I will have a standing to advise and mobilize other workers. I want to learn how to get the message across – seeing people on the same quest helps.

The project team also formed a participatory research collaboration with the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health as well as worker centers in Chicago and seven other cities as part of the “More than Training” initiative.8,9 This initiative received additional funding from NIOSH to support worker trainees, to engage additional authorized bilingual OSHA trainers, and to disseminate and evaluate the training model. Hands-on peer education was used to provide the entire OSHA 10-hour training to workers with OSHA-authorized trainers participating in the background. OSHA 10-hour training is becoming a requirement for entry onto many construction sites. For many day laborers, the OSHA-10 card is viewed as an important sign of achievement and as proof that they know their way around a construction site, a valuable tool for obtaining work with better employers. During this initiative, OSHA 10-hour cards were issued to 445 workers completing the training. The participating centers saw the project as strengthening not only the leadership skills of the workers, but also building capacity within the centers themselves.

By the end of the first five years, interviews with New Labor’s peer educators revealed the extent to which they had begun to talk about health and safety on the corners with their co-workers, speak up to employers or simply walk away from dangerous work.10,11,12 More than education was clearly needed. Training by itself could not lead to significant changes at worksites where the infrastructure was not safe. What were the strategies needed to enhance safety practices on the job? Workers identified many needs. Fellow workers often needed to take a long-term view of their own health and safety: while risky jobs take on an air of inevitability when workers are desperate, workers needed to consider the fate of their families if they were disabled or killed. Workers needed skills to help them persuade coworkers to stand up for safety and to communicate with employers. When workers convinced employers to provide necessary PPE or use safe work practices, everyone on the job benefitted. When that didn’t work, being able to forge a group response with fellow workers, often calling in New Labor staff, sometimes helped. When all else failed, workers needed to communicate with OSHA and get a response. Each of these actions posed challenges.

Creating a role to meet an emerging need

OSHA-authorized trainer Selvin Trejo leads a session for workers

who have shown leadership skills and seek to become safety

liaisons.

Some co-workers had set up a scaffold incorrectly – I told them how to set it up.

Now I ask questions to know I’ll be safe. When I get to the job, I first look around and then I ask if they have the equipment [to work safely]. If they don’t have it, I tell them I’m sorry, I can’t do the job.

For safety liaisons, knowing how to identify and report health and safety hazards commonly experienced by day laborers is a fundamental skill. Within their first year, the liaisons helped Rutgers researcher Elizabeth Marshall and experts from the New Jersey Laborers Health and Safety Fund develop and evaluate a checklist tool to conduct safety audits. The liaisons worked with the Rutgers and New Labor team to practice documenting worksite hazards. With a paper audit checklist that fit into their back pocket, the liaisons recorded observations on more than 200 work sites to monitor the progress of the project. The audits showed consistent problems at construction work sites. For example, only about 50% of job sites were supplied with hard hats and less than half had fall protection provided as required for scaffolds or other elevated surfaces. The liaisons often (about 60% of job sites) talked to their co-workers about possible problems at their jobs and sometimes (about 35% of job sites) suggested changes to the foreman.

In safety liaison training, students will learn how to respectfully

approach a contractor with an identified safety hazard – and how

to reduce or eliminate it.

Growing into a leadership role

Over the course of the five years, the workers selected as safety liaisons grew into their roles as peer safety leaders. In the first two years of the program, they were comfortable being introduced as safety liaisons when they were leading a training class, but they were uncomfortable embracing this role on the worksite or in public settings with their peers.

Feeling like leaders outside the classroom did not come easy. New Labor staff worked hard to develop experiential exercises on communication, active listening, creating agendas, and running meetings. These “soft skills” were as important as the technical training in helping liaisons feel like they could lead effectively. To build solidarity and a sense of group identity, the liaisons were encouraged to work together to identify priorities and create the rules and structure for meetings and continuing as liaisons. Experienced liaisons took the lead in recruiting, selecting and mentoring new liaisons. As they were trained and encouraged to represent the project, organize meetings, and present health and safety information, the liaisons participated in community forums. Eventually the liaisons took a giant step forward, creating their own Worker Council (Consejo) in the Ironbound community to share labor rights information and provide guidance on addressing wage violations and health and safety complaints for workers who were in the same position the liaisons struggled with just a few years ago. Through outreach to workers in their community, liaisons have generated a beehive of activity at New Labor’s Newark office. Safety liaisons expanded their circle to aid more workers: they began mentoring and supporting newly trained safety liaisons across the river – at the Brooklyn-based Worker Justice Project.

Feeling like leaders outside the classroom did not come easy. New Labor staff worked hard to develop experiential exercises on communication, active listening, creating agendas, and running meetings. These “soft skills” were as important as the technical training in helping liaisons feel like they could lead effectively. To build solidarity and a sense of group identity, the liaisons were encouraged to work together to identify priorities and create the rules and structure for meetings and continuing as liaisons. Experienced liaisons took the lead in recruiting, selecting and mentoring new liaisons. As they were trained and encouraged to represent the project, organize meetings, and present health and safety information, the liaisons participated in community forums. Eventually the liaisons took a giant step forward, creating their own Worker Council (Consejo) in the Ironbound community to share labor rights information and provide guidance on addressing wage violations and health and safety complaints for workers who were in the same position the liaisons struggled with just a few years ago. Through outreach to workers in their community, liaisons have generated a beehive of activity at New Labor’s Newark office. Safety liaisons expanded their circle to aid more workers: they began mentoring and supporting newly trained safety liaisons across the river – at the Brooklyn-based Worker Justice Project.

When Hurricane Sandy tore through New Jersey in 2012, the recovery efforts generated a wave of demolition, clean-up, and residential construction. Along with building came a huge opportunity to identify and correct safety and health hazards. Safety liaisons joined street teams in affected areas, handing out bags of personal protective equipment (PPE) to workers in the field and providing brief demos and trainings on corners. They worked with New Labor staff to conduct audits of hazardous construction sites along the Jersey shore, where they continued to reach out to workers, employers, and OSHA.

My motivation is to learn about the organization and educate myself about rights, health and safety. I would like to know how to organize more people to build New Labor – to become more of a leader.

I was on a job with J. [He] was in a trench about 10 feet high – I told him to get out – a few minutes after he climbed out, the trench collapsed ….

Earning credentials – and respect

Students celebrate completion of training and the beginning of

a new role: Safety Liaisons.

One of the breakthrough events occurred in 2014 when four of the Safety Liaisons became OSHA-authorized trainers, a significant achievement. Completing the OSHA 500-level classes delivers a level of skill and autonomy that authorizes these Safety Liaisons to provide training and issue OSHA-10 cards to those who meet the requirements. This not only enriched the leadership role already taken by these workers, it offers a model for future expansion of safety and health within the immigrant Latino community. More than 500 workers in New Jersey and New York have received OSHA- 10 cards through trainings facilitated by New Labor’s safety liaisons.

In a highly positive turn of events that few thought would happen, the classes began drawing contractors who bring their entire crew. Approximately 50 workers have been trained along with crew leaders.

I started to communicate with [one of] my bosses about the importance of hard hats and safety glasses. He has forced everyone to use them for the past year and a half. They know I will report them to OSHA.

OSHA-authorized instructors Selvin Trejo, Edison

Flores and Jonass Mendoza at an OSHA-10 class.

Safety liaisons embraced their role to such a degree that they did things most average Americans have never done. Safety liaisons have exchanged comments and questions with Dr. David Michaels, Assistant Secretary of Labor for Occupational Safety and Health (OSHA), and they have met with OSHA Region 2 officials. They have made presentations at safety conferences attended by professionals with years of experience. They shared their experiences with other immigrant workers through national meetings of the National Day Laborers’ Organizing Network and the Interfaith Worker Justice network.13

In April 2014, two safety liaisons and New Labor’s executive director traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify in favor of stronger OSHA silica standards. They were joined by five Latinos workers from other centers, becoming the first immigrants to testify at an OSHA standards hearing in Spanish. Workers clearly identified the hazards they face, as silica dust is inhaled during demolition and other jobs. Silica dust scars the lungs, reducing a worker’s ability to breathe. Silica is a known carcinogen and causes silicosis (an incurable disease) and lung cancer, plus other lifeshortening health problems.

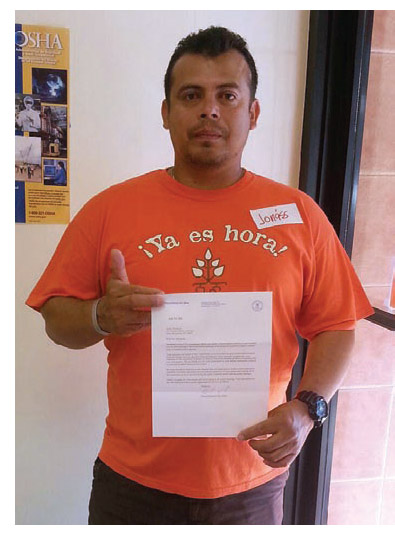

From the testimony of Jonass Mendoza:

Jonass Mendoza holds a letter of thanks from OSHA head Dr.

David Michaels. Mendoza delivered testimony during OSHA’s

hearings on a proposed silica rule in March of 2014.

We are exposing ourselves to demolition jobs in inadequate places, places that are not cleaned, places where there is not even a place to wash your hands before eating. Places where everything is covered in dust…. I believe that we all should have the right to safe workplaces. I know that we can accomplish this if we combine our strength to make this change.

None of these achievements were (or are) easy. Safety Liaisons experienced indifference from many of their co-workers, hostility and threats from their own bosses and from others contractors hiring day laborers. Evening meetings can be exhausting after long workdays and long commutes. Immigration issues don’t go away. Sharing the failures helped – but sharing the successes helped more.

The safety liaisons realize they have accomplished a great deal …

We have training and we don’t have to fear the boss. We also have power. We are trained to talk to the boss one-on-one.

I was painting a very steep dome inside a church. I asked my boss for the PPE and he gave me everything because I knew what to ask for.

This work has not ended

You can’t count on employers to take care of you. I was helping my contractor help another contractor, but [he] wanted us to cut tiles. He didn’t have the right machine to do wet cutting. I refused – said there would be too much dust. The contractor took the saw and said, “I’ll do it myself” – he saw there was a lot of dust. He went out and bought the right kind of masks and saw.

As the Rutgers researchers measured the project’s impact and New Labor’s ability to get day laborers involved, the team began looking to the future. Based on their experience, New Labor sees the role of safety liaisons as central to their work in engaging and inspiring workers not familiar with a worker center organization. They realized that liaisons are self-sustaining, as they continue to bring in new workers, identify those with leadership and/or training potential, and begin grooming them for those roles. Now safety liaisons have a new role: mentoring New Labor members facing serious hazards in warehousing and manufacturing.

As the Rutgers researchers measured the project’s impact and New Labor’s ability to get day laborers involved, the team began looking to the future. Based on their experience, New Labor sees the role of safety liaisons as central to their work in engaging and inspiring workers not familiar with a worker center organization. They realized that liaisons are self-sustaining, as they continue to bring in new workers, identify those with leadership and/or training potential, and begin grooming them for those roles. Now safety liaisons have a new role: mentoring New Labor members facing serious hazards in warehousing and manufacturing.

The Rutgers-New Labor team sees two priorities: first, developing more direct communication with contractors and encouraging increased participation by contractors in the 10-hour training and second, creating career ladders for the safety liaison into the role of foreman at construction sites. As an integral part of the training programs, the safety liaison positions could be sustained through increased employer-sponsored training for workers and supervisors.

Safety liaisons inspect a site with obvious

dangers from the street and, if possible,

engage with workers. The liaisons have

come full circle, bringing their knowledge

to people threatened by the same

conditions they once faced.

The Rutgers-New Labor team, in close collaboration with the immigrant Latino worker community, recently produced a complete curriculum for training immigrant Latino day laborers on basic safety and health practices on construction sites, and they are making it available to all interested organizations and individuals. Because the training program evolved and improved through the interactions, trials and errors, and suggestions of the Latino students, the curriculum is designed to engage students and instructors in highly interactive and results-driven ways. The curriculum has been used by the worker centers in two New Jersey locations and Brooklyn, New York, as well as worker centers in Chicago, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Houston, Phoenix, Memphis, Tenn., and Austin, Texas, that participated in the “More Than Training” initiative through the UIC-Rutgers participatory research project.

The Training Manual (The Day Laborers’ Health and Safety Workbook and La Salud y Seguridad en la Construccion Residencial) – plus a Trainer Guide that walks an individual through the steps to deliver the training are recently updated and available online in English and in Spanish, all at no charge. Training tools are also posted: a baseline survey to determine the experiences and current knowledge of the workers, and a follow-up survey for Safely Liaisons. Safety Liaisons are trained to use a Construction Safety Checklist to quickly assess if a worksite has hazards; that tool is available in English and Spanish.

You can find these materials on CPWR’s website, www.cpwr.com. They are also posted on the electronic Library of Construction Occupational Safety and Health, www.elcosh.org (English) and www.elcosh.org/es (Espanol).

Low-wage, high-risk workers throughout the U.S. have come together through immigrant worker centers and other organizations to promote respect, justice, and recognition of workers’ rights. Workplace safety and health campaigns strengthen workers and their organizations. New Labor, Rutgers University researchers and CPWR – The Center for Construction Research and Training are proud to make these and other bilingual training materials available to organizations seeking to improve and strengthen the lives of Latino workers and their community.

Most important is protecting my life and my co-workers.

For more information, contact:

Michele Ochsner, PhD

Rutgers Occupational Training and Education Consortium

848-932-5587

mochsner@work.rutgers.edu

Louis Kimmel

Executive Director, New Labor

732-246-2900

lkimmel@newlabor.org

Betsy Marshall, PhD

Rutgers University School of Public Health

732-235-4666

marshaeli@sph.rutgers.edu

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the leadership, vision and courage demonstrated by the New Labor Safety Liaisons present and past including Edison Flores, Norlan Trejo, Selvin Trejo, José Luis Martínez, Jonass Mendoza, Julio Cesarto, José Gregorio Sánchez, Juvenal Ramon, Efraín Vásquez, Claudio Yunga, and Miguel Barahona.

References

- Lee MA and Mather M. 2008. U.S. Labor Force Trends, Population Bulletin. The Population Reference Bureau. https://assets.prb.org/pdf08/63.2uslabor.pdf (Accessed October 2014)

- Richardson S. 2005. Fatal work injuries among foreign-born Hispanic workers. BLS Monthly Labor Review, pg. 65. http://www.bls.gov/opub/ mlr/2005/10/ressum.pdf (Accessed October 2014)

- Dong X, Largay J, Wang W. 2014. New Trends in Fatalities among Construction Workers. CPWR Data Brief, Vol. 3 No. 2, pg. 3, chart 4. http:// www.cpwr.com/sites/default/files/publications/ New%20Trends%20in%20Fatalities%20 among%20Construction%20Workers.pdf

- CPWR Data Center. 2013. The Construction Chart Book, pg. 44, chart 44b. http://www.cpwr.com/publications/construction-chart-book

- Dong X, Largay J, Wang W. 2014. New Trends in Fatalities among Construction Workers. CPWR Data Brief, June 2014, Vol. 3 No. 2, pg. 8, chart 13. http://www.cpwr.com/sites/default/files/ publications/New%20Trends%20in%20 Fatalities%20among%20Construction%20 Workers.pdf

- Ochsner M, Marshall E, Kimmel L, Martino C, Cunningham R, Hoffner K. 2008. Immigrant Day Laborers in New Jersey: Baseline Data from a Participatory Research Project. New Solutions: Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 18 (1): 57-76. http://www. researchgate.net/publication/5477989_ Immigrant_Latino_day_laborers_in_New_Jersey_ baseline_data_from_a_participatory_research_ project

- Williams Q , Ochsner M, Marshall E, Kimmel L, Martino M. 2010. The Impact of a Peer-led Participatory Health and Safety Training Program for Latino Day Laborers in Construction. Journal of Safety Research. 41: 253–261. http://www. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0022437510000344

- Forst L, Ahonen EQ, Zanoni J, Holloway, Ochsner M, A. Kimmel L., Martino C, Rodriguez E, Kader A, Ringholm E, and Sokas R. 2013. More than Training: Community Based Participatory Research to Prevent Injuries in Hispanic Construction Workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. Article first published online : 26 MAR 2013, DOI: 10.1002/ajim.22187 http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23533016

- Ahonen EQ, Zanoni J, Forst L, Ochsner M, Kimmel L, Martino C, Ringholm E, Rodríguez E, Kader A, Sokas R. 2013. More than training: Evaluating goals large and small in worker health protection using a participatory design and an evaluation checklist. New Solutions Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy: 23(4)537-60.

- Ochsner M, Marshall E, Kimmel L, Martino C, Cunningham R, and Hoffner K. 2008. Immigrant Day Laborers in New Jersey: Baseline Data from a Participatory Research Project. New Solutions: Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 18 (1): 57-76 http://www. researchgate.net/publication/5477989_ Immigrant_Latino_day_laborers_in_New_Jersey_ baseline_data_from_a_participatory_research_ project

- Williams, Q., Ochsner, M. Marshall, E., Kimmel, L., and Martino M. 2010. The Impact of a Peer-led Participatory Health and Safety Training Program for Latino Day Laborers in Construction. Journal of Safety Research. 41: 253–261. http:// www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0022437510000344

- Empowering Day Laborers to Work Safely in Construction. 2011. CPWR IMPACT card. http://www.cpwr.com/sites/default/files/ publications/ EmpoweringDayLaborsIMPACTCardPDF.pdf

- Ochsner M, Marshal E, Kimmel L, Martino C, Pabelón M, Rostran D. 2012. Beyond the Classroom—A Case Study of Immigrant Safety Liaisons in Residential Construction. New Solutions: Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy. 22:3 2012 pg 365-86 (December 2012 special issue on training). http://www.unboundmedicine.com/medline/citation/22967368/Beyond_the_

classroom:_a_case_study_of_immigrant_safety_liaisons_in_residential_

construction_

©2014, CPWR – The Center for Construction Research and Training. All rights reserved. CPWR is the research, training, and service arm of the Building and Construction Trades Dept., AFL-CIO, and works to reduce or eliminate safety and health hazards construction workers face on the job. Production of this report was supported by Grant OH009762 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH.