OSHA Resource for Development and Delivery of Training to Workers

Summary Statement

More than 100 of OSHA’s current standards contain requirements for training. Furthermore, a comprehensive workplace safety program needs to include training. This OSHA guide outlines information on developing and delivering effective training to workers.

2015

Photo courtesy of ACTA.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Characteristics of Sound Training Programs

- Overview of Best Practices for Training Adults

- Principles of Adult Education

- Program Design, Delivery, and Evaluation Elements

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D

- Appendix E

- OSHA Educational Materials

- Workers’ Rights

- OSHA Regional Offices

- How to Contact OSHA

Introduction

More than 100 of OSHA’s current standards contain requirements for training. Furthermore, a comprehensive workplace safety program needs to include training. This OSHA guide outlines information on developing and delivering effective training to workers.

Quality safety and health training helps prevent work-related injuries and illnesses. Effective training also encourages workers by educating and empowering them to advocate for safer working conditions.

Several factors contribute to successful training. One of the most important is ensuring that the training facilitator exhibits safety and health expertise, sound instructional skills and flexibility. This guide is a framework to ensure that quality training is developed and delivered. In effective training, participants should learn:

- How to identify the safety and health problems at their workplace;

- How to analyze the causes of these safety and health problems;

- How to bring about safer, healthier workplaces; and

- How to involve their co-workers in accomplishing all of the above.

Other voluntary standards and minimum criteria guidance on developing and delivering safety and health training exist and OSHA encourages you to review these documents as well:

- ANSI/ASSE Criteria for Accepted Practices in Safety, Health, and Environmental Training, ANSI/ ASSE Z490.1-2009

- ANSI: American National Standards Institute

- ASSE: American Society of Safety Engineers

- NIEHS WETP Minimum Health and Safety Training Criteria Guidance for Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER); HAZWOPER Supporting and All Hazards Prevention, Preparedness and Response.

- NIEHS: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

- WETP: Worker Education and Training Program

Characteristics of Sound Training Programs

A general review of training “best practices” reveals four characteristics that sound training programs have in common. The best training programs are accurate, credible, clear and practical.

Accurate. Training materials should be prepared by qualified individuals, updated as needed, and facilitated by appropriately qualified and experienced individuals employing appropriate training techniques and methods.

Credible. Training facilitators should have a general safety and health background or be a subject matter expert in a health or safetyrelated field. They should also have experience training adults or experience working with the target population. Practical experience in the field of safety and health as well as experience in training facilitation contribute to a higher degree of facilitator credibility.

Clear. Training programs must not only be accurate and believable, but they must also be clear and understandable to the participant. If the material is only understandable to someone with a college education or someone who understands the jargon, then the program falls short of meeting workers’ needs.

Training materials should be written in the language and grammar of the everyday speech of the participants. Training developers should ensure that readability and language choices match the intended audience.

If an employee does not speak or comprehend English, instruction must be provided in a language that the employee can understand. Similarly, if the employee’s vocabulary is limited or there is evidence of low literacy among participants, the training must account for this limitation. Remember that workers may be fluent in a language other than English, or they may have low literacy in both English and their primary language. Training needs to be adjusted to accommodate all the factors that are present.

Practical. Training programs should present information, ideas, and skills that participants see as directly useful in their working lives. Successful transfer of learning occurs when the participant can see how information presented in a training session can be applied in the workplace.

Overview of Best Practices for Training Adults

Training providers and instructional facilitators who recognize and embrace characteristics of sound training and principles of adult education will maximize the benefits of the training for their participants.

- Intended audience. This guidance is intended for employers, safety officers or any organization that provides occupational safety and health training.

- Training techniques, methods and modes.

- Proven adult learning techniques should be at the core of training development and delivery.

- Peer-to-peer training with activitybased learning is one effective model for worker training. Effective development of peer trainers requires ongoing organizational support to the developing peer trainer.

- Activity-based learning should fill at least two-thirds of training hours (no more than one-third is lecture).

- Training must be provided in a way that workers receiving it can understand. In practical terms, this means that the training must be both in a language and vocabulary that the workers can understand.

- While computer-based training (CBT) can augment the effectiveness of safety and health training for workers, it should not be the sole form of training that workers receive.

- Needs assessment. Safety and health training should be preceded by a needs assessment to ensure the training meets the needs of the participants. Needs assessments can also be used to learn more about your target population’s knowledge, experience, learning styles, reading and writing skills, and interests.

- Evaluation of Training. Evaluating your training allows you to assess whether the training is having the desired results, and informs you as to whether you need to make changes to your training program.

Principles of Adult Education

The following are the basic principles of how adults learn, which is directly applicable to safety and health training programs:

- Adults are voluntary learners: Most adults learn because they want to. They learn best when they have decided they need to learn for a particular reason.

- Adults learn needed information quickly: Adults need to see that the subject matter and the methods are relevant to their lives and to what they want to learn. They have a right to know why the information is important to them.

- Adults come with a good deal of life experience that needs to be acknowledged: They should be encouraged to share their experiences and knowledge.

- Adults need to be treated with respect: They resent an instructor who talks down to them or ignores their ideas and concerns.

- Adults learn more when they participate in the learning process: Adults need to be involved and actively participating in class.

- Adults learn best by doing: Adults need to “try-on” and practice what they are learning. They will retain more information when they use and practice their knowledge and skills in class.

- Adults need to know where they are heading: Learners need “route maps” with clear objectives. Each new piece of information needs to build logically on the last.

- Adults learn best when new information is reinforced and repeated: Adults need to hear things more than once. They need time to master new knowledge, skills, and attitudes. They need to have this mastery reinforced at every opportunity.

- Adults learn better when information is presented in different ways: They will learn better when an instructor uses a variety of teaching techniques.

Three kinds of “learning exchanges”:

- Participant-to-Participant: “Participant-toparticipant” learning exchange recognizes that participants can learn from one another’s experiences. Participant-toparticipant exchanges should be a key feature of the training.

- Participant-to-Facilitator: Facilitators can learn as much from training sessions as participants do. On many subjects, a group of participants may have more extensive knowledge and experience in certain areas than a facilitator.

- Facilitator-to-Participant: Classroom learning needs structure. A facilitator’s role is to guide discussions, encourage participation, draw out and/or add information as needed, and highlight key issues and points.

The Principles of Adult Education: A Checklist

Material adapted from Teaching About Job Hazards, Nina Wallerstein and Harriet Rubenstein, American Public Health Association, 1993.

General Principles

The best training programs take advantage of the following characteristics of adult learners:

- Adults are self-motivated.

- Adults expect to gain information that has immediate application to their lives.

- Adults learn best when they are actively engaged.

- Adult learning activities are most effective when they are designed to allow students to develop both technical knowledge and general skills.

- Adults learn best when they have time to interact, not only with the instructor but also with each other.

- Adults learn best when asked to share each other’s personal experiences at work and elsewhere.

Environmental and Learning Needs Assessments

- Does the learning environment encourage active participation?

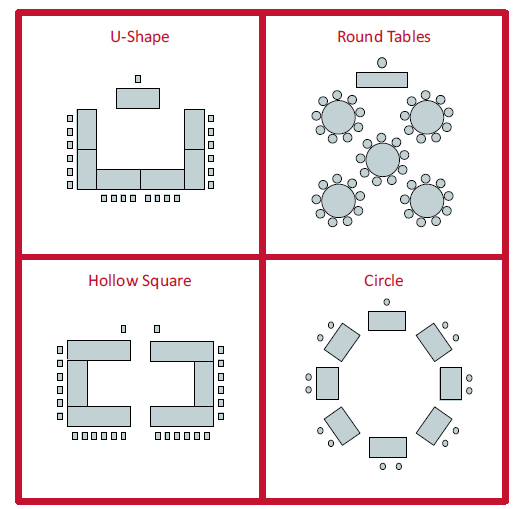

- How are the chairs, tables, and other learning stations arranged in the classroom?

- How does this arrangement encourage or inhibit participation and interaction?

- Can the arrangement be changed easily to allow different kinds of interaction?

- Is the climate of the classroom sufficiently comfortable to allow learning?

- Does the social environment or atmosphere in the learning environment encourage people to participate?

- Are warm-up activities or “ice breakers” needed to put people at ease?

- Do trainers allow participants to say things in their own words, or do they translate what is said into other words or jargon?

- Are participants encouraged to listen carefully to each other?

- Are they encouraged to respect different points of view?

- Are they encouraged to use humor and is the humor appropriate?

- People learn in different ways. Do the learning activities in the training program provide participants with an opportunity to do each of the following?

- Listen

- Look at visuals

- Ask questions

- Read

- Write

- Practice with equipment (if applicable)

- Discuss critical issues

- Identify problems

- Plan actions

- Try out strategies in participatory ways

- Does the program effectively promote participatory learning activities?

- Is enough time allotted for participant interaction?

- Have the instructors developed workable and effective interactive activities?

- Does the physical environment encourage interaction?

- Does the atmosphere in the classroom encourage interaction?

- Are the learning activities sensitive to cultural differences among the participants?

- Does the training engage participants in critical thinking and analysis about the subject being covered?

- How effectively do the lectures in the program encourage participation?

- Are they combined with a participatory exercise?

- Are they brief?

- Are they well organized?

- Are audio-visual aids incorporated in the lecture?

- Does the lecturer rely too heavily on his or her notes?

- Was there enough time for questions and comments from others?

- Does the lecturer promote challenging questions about the content being delivered?

- How effective are the participatory activities used in the program?

- Are the purposes of the activities clearly specified?

- Are the tasks that people are expected to complete clearly described?

- Are participants given enough information to complete the expected tasks?

- Is the information accompanying the activity clearly presented and easily understood?

- Is the information presented relevant to the task?

- Are participants given enough time to perform the expected tasks?

- Are participants given enough time to share what they have learned from the tasks with each other?

- Are the participants given a clear summary of the main points they were expected to learn in the activity?

- If case studies or roll-playing is used, do the case studies and role-playing activities in the program encourage participation?

- Is the situation being discussed familiar to the participants?

- Does the situation evoke strong feelings in the participants?

- Does the situation lead to an in-depth analysis of the problem?

- Does the situation encourage people to consider a range of possible strategies for dealing with the problem?

- Are people provided with enough information to participate in the activity in a meaningful way?

- Are people provided with so much information that they have no room to improvise or to call on their own experience?

- Are people provided with an opportunity to discuss the social, cultural, and historical contexts of the situations?

- How effectively does the organization of the program encourage participation?

- Are discussion groups small enough to ensure participation? (No more than 4 to 6 people.)

- Is the ratio of discussion groups to instructors small enough? (A single instructor cannot effectively supervise more than three or four groups).

- Is there enough room to enable each group to talk amongst itself without disruption?

- Does the responsibility for leading and recording the discussion rotate among those willing to do the job?

- Are the groups supplied with guidelines about how to lead and report their discussions?

- Do the activities make allowances for anyone in the group who may have problems reading and writing?

- Is the program sensitive to literacy differences?

- Do the trainers check privately with anyone having reading and writing difficulties?

- Is reading aloud or writing in front of the group only voluntary and never mandatory?

- Are all instructions and other required material read aloud?

- Do the materials incorporate enough visual aids and props?

- Do the trainers repeat out loud anything they write on a board or flip chart?

- Are evaluations conducted to assure that the trainees comprehend the training material?

- Do the audio-visual aids used by the training program encourage participation?

- Do the instructors write an on-going record of what is being discussed on the board or flip charts?

- Are participants encouraged to challenge the record if they consider it inaccurate?

- Are approaches utilizing integrated instructional technologies effective in eliciting participation?

Program Design, Delivery, and Evaluation Elements

This document categorizes the elements into four sections: Training Facilities and the Learning Environment; Training Course Materials and Content; Training and Overall Program Evaluation; and Specific Populations to Consider.

Training Facilities and the Learning Environment

Ideally, training facilities should have sufficient resources and equipment to perform classroom and activity-based learning in a setting conducive to effective learning.

However, often such facilities are not available and instructors find themselves having to make do and adapt to training in the environment they are given. Sometimes training will be conducted in remote or non-traditional locations. You may be in a smaller room than anticipated, or there may be no electrical outlets or flip charts in the room where you are training. Trainers should anticipate such setbacks and prepare as best as they can.

Instructor-trainee ratios. Class sizes of about 25 people (or less) work best, especially when incorporating activity-based learning into the training experience. When class size exceeds 30 people, it is advisable to provide a second instructor and divide the class into two sections during instruction.

Training Facilities and Resources

Adequate and appropriate facilities for supporting training include:

- Sufficient space for all attendees to sit comfortably during instruction;

- Sufficient room set-up for participants to interact with one another;

- Enough equipment for all attendees and demonstration equipment for the instructor/facilitator (if applicable);

- Space and facilities for small group exercises or hands-on training using equipment as part of activity-based learning; and

- Equipment, technical support, and resources sufficient to support training via technology, such as during instructor presentations or web-based training used by students to enhance learning (if applicable).

Training Course Materials and Content

Training Development/Instructional Design

Training courses should be developed and updated as necessary to be consistent with the recognized principles of training development/ instructional design. Training development should follow a systematic process that includes: a needs assessment, learning objectives, adult learning principles, course design, and evaluation. (Reference: ANSI Z-490.1-2009.)

One such instructional design model is called “ADDIE.” This stands for the main components of the ADDIE process: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation. Training materials and content are produced as the course author progresses through the instructional design cycle. First, a training analysis is performed, then the structure of the course is designed; next, specific content is developed; after that, the course is implemented or presented; and last, the course is evaluated.

Particular attention should be devoted to the following with respect to course design and content:

- Demographics of the training target audience and their training needs; for instance, what is the literacy level of your target audience?

- Learning objectives, including learning objectives for each training module.

- Analysis and selection of a delivery method appropriate to the training target audience and the learning objectives.

- Instructional materials including, but not limited to, an instructor’s manual with lesson plans and learning objectives, a trainee manual, training aids, and learning technologies.

Training Objectives

Every instructor has objectives he/she wishes to accomplish during training. Instructional objectives should be student-focused and state the desired learning outcome. However, it is necessary to note that, while good training can be provided, workers can still face difficulty at work when raising their voices to try to get problematic conditions corrected.

When constructing objectives, the main question that objectives answer is: What should the participant be able to do differently, or more effectively, after the training is completed?

The SMART Model is one method used to construct practical objectives.

- “S” stands for Specific. Objectives should specify what they need to achieve.

- “M” stands for Measurable. You should be able to measure whether you are meeting the objectives or not.

- “A” stands for Achievable. Objectives should be attainable and achievable.

- “R” stands for Relevant. Objectives should lead to the desired results.

- “T” stands for Time-bound. When do you want to achieve the set objectives?

Other training objective construction models include the A-B-C-D Model and Roger Mager’s Theory of Behavioral Objectives.

The A-B-C-D Model:

- “A” stands for audience. State the learning audience within the objective.

- “B” stands for behavior. State the behavior you wish to see exhibited following training.

- “C” stands for condition. State the conditions under which the behavior will occur.

- “D” stands for degree. To what level (or degree) will the learner be enabled to perform?

Roger Mager’s Theory of Behavioral Objectives has three components:

- Behavior: The behavior should be specific and observable.

- Condition: The conditions under which the behavior is to be completed should be stated, including what tools or assistance is to be provided.

- Standard: The level of performance that is desirable should be stated.

Note that training objectives emphasize what the participant will be able to do, not what the instructor intends to do. In each example, workers are expected to be able to accomplish specific goals by the end of the course.

When developing learning objectives, be mindful of what is in your control in the classroom and what is out of your and the participants’ control in the workplace.

Addressing Literacy in Teaching Methods and Materials

Literacy can be defined as the ability to “use printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.” (National Coalition for Literacy, 2009.)

Some workers, including those born in the U.S., have limited literacy in their primary language. More than one-third of recent immigrants have fewer than 12 years of education. Among those from Latin America, 35% have less than a ninth grade education. Low-literacy training materials and teaching methods that are not limited to written materials should be prepared or acquired to meet the needs of this type of training audience. (Reference: Draft Immigrant Worker Safety and Health Report, NIOSH and University of Massachusetts — Lowell.)

Multiple training methods that require fewer literacy skills should be used with this population. Methods include the use of photos, pictures, short role-plays, case studies, demonstrations, hands-on practice, and small group activities with which workers can identify and easily understand.

Training Techniques to Reach All Literacy Levels

The following suggestions are designed to help trainers adapt training techniques to reach participants at all skill/literacy levels. These techniques will also be helpful in teaching participants for whom English is a second language (sometimes referred to as English Language Learners (ELL)).

- Do not assume that all participants are equally skilled or confident in speaking, reading, writing, and math.

- Plan for plenty of small group activities where participants get to work together on shared tasks — reading, discussing, integrating new information, relating to life experience, recording ideas on flip charts, and reporting back to the whole group. In small groups, participants can contribute to the tasks according to their different backgrounds and abilities.

- Try to use as many teaching techniques as possible that require little or no reading.

- At the beginning of a class mention that you are aware that people in the group may have different levels of reading and writing skills.

- Establish a positive learning situation where lack of knowledge is acceptable and where questions are expected and valued. Participants need to be able to indicate when they do not understand and to feel comfortable asking for explanations of unfamiliar terms or concepts.

- Make it clear that you will not put people on the spot. Let them know that you are available during breaks to talk about any concerns.

- Let the group know that they will not necessarily be expected to read material by themselves during the training.

- Let people know that you will not be requiring them to read aloud. Ask for volunteers when reading aloud is part of an activity. Never call on someone who does not volunteer.

- Do not rely on printed material alone. When information is important, make sure plenty of time for discussion is built into the class so participants have the opportunity to really understand.

- Read all instructions aloud. Do not rely on written instructions or checklists as the only way of explaining an activity or concept.

- If other materials must be read aloud, read them yourself or ask for a volunteer.

- Make sure your handouts are easy to read and visually appealing.

- Give out only the most important written material. Make any other materials available as an option.

- If possible, provide audio recordings of key readings so that participants have the option to listen and read along.

- Explain any special terms, jargon, or abbreviations that come up during the training. Write them on a flip chart.

- If participants have to write, post a list of key words. This can serve as a resource for people with writing or spelling difficulties.

Participatory Methods of Instruction

Participatory training methods draw on participants’ own experiences. They encourage teamwork and group problem solving. Participants have the opportunity to analyze safety and health problems in a group and to develop solutions. There can also be valuable exchanges between workers and trainers about their lives and work.

Participatory methods work quite well with people who have difficulty reading and writing. They also allow the instructor to observe who may be having difficulty with the concepts and to engage with them to ensure comprehension. Participatory methods (1) draw on the participants’ own knowledge and experience about safety and health issues; (2) emphasize learning through doing without relying on reading; and (3) create a comfortable learning experience for everyone.

Samples of Participatory Methods

Participatory training methods draw on the trainee’s own experiences and knowledge, as well as encourage valuable exchanges between workers and trainers. The following are examples of methods to encourage trainees to participate and be actively engaged in class:

- Ice-breakers

- Risk maps

- Role-playing

- Games

- Small group exercises

- “Trigger” visuals

- Brainstorming

- Demonstrations and hands-on activities

- Participatory lectures

Training Materials

Training materials, such as handouts, PowerPoint presentations, or flip charts, are often used as visual aids to facilitate and enhance the student’s learning experience. Materials should be easy-to-read and should highlight the most important messages or needs. Keep in mind that visual aids—such as PowerPoint presentations, handouts, overheads, and flip charts—play a supportive role to the main teaching technique and do not substitute for teaching.

The following are some principles for creating the text for easy-to-read materials:

- Base the content on the workers’ most important needs.

- Identify the “priority message.” The priority message should convey the most important information about a problem and how it could be solved. It should be short, informative, and easy to remember.

- Don’t offer so much information that a reader could feel overwhelmed.

- Organize text into short, logical sections by using headings or subtitles.

- Use words that are easy to understand.

- Define technical terms or jargon.

- Keep sentences short and simple.

- Use a conversational style and active voice, such as the kind of language that the students use.

The design of the material is as important as the content. Making the material visually appealing and easier on the eye will encourage people to read it. The following are tips for the design of the materials:

- Use a large, easy-to-read font for the main text.

- Emphasize important points with underlining, bold type, italics, or boxes.

- Include plenty of white space by using wide margins.

- Use plenty of simple illustrations to explain the text.

- Use simple line drawings that are free of clutter and abstract drawings.

Using PowerPoint

PowerPoint is not a teaching technique—it is a visual aid that can be used to enhance learning, just like flip charts, overheads, and handouts. PowerPoint will not, in and of itself, improve student learning. It is the way that instructors use PowerPoint that can encourage learning. Deciding when, where, and how it can be used appropriately is the key.

Many instructors mistakenly use PowerPoint as their main teaching technique. If an instructor teaches only by showing and reading a PowerPoint presentation, there is not much opportunity for participation. In fact, use of PowerPoint can stifle participation. The teaching turns out to be “one-way”, similar to the “traditional” model of education with the instructor as expert and the students just as the receivers of information. As mentioned previously, adult education is most effective when it is participatory—when students are active participants in the learning process.

Educators need to be creative in using PowerPoint. If you plan to use PowerPoint, it is critical that it be used in such a way that participants retain and use the information, as well as participate in the learning experience.

There are three main issues to consider when using PowerPoint: content, design, and delivery.

Content:

- If you are creating PowerPoint presentations, it is best to plan your workshop or class first and then write the content of the PowerPoint slides.

- Include the main points, not lots of text.

Design:

- One concept per slide.

- Use a simple design.

- Make sure you really understand how to create and design PowerPoint slides. It takes some knowledge and skill to develop a PowerPoint presentation. For instance, getting the animation correct can be tricky.

- Do not make the mistake of designing the PowerPoint with too many graphics and animation (a common error among instructors). This can result in a design that is too complicated and difficult to read. Go easy on the graphics. Simple graphics that are easily understood are best. Do not use graphics just to make a slide look good; only use them if they have some content value. Keep animation to a minimum.

- Use lots of white space.

- Use contrast: dark on light, or light on dark. In choosing colors, make sure that the text is easy to see.

- Design from top left to bottom right.

- Use large font sizes (26 point minimum). No more than two fonts on a page.

- Limit use of bolding, italics and underlining.

Delivery:

- Remember that PowerPoint is a visual aid, not a teaching technique.

- Your slides should serve as a focal point for the issues to be discussed. Use them to help control the pace of presentation and discussion. Read a slide aloud and follow with commentary, explanation and discussion. Remember questions and discussion are part of the learning experience.

- Practice using PowerPoint before you actually use it in a class. Make sure you are comfortable moving between slides and between information on slides.

A final note on technology: Using PowerPoint requires that you have all the technology you need, that it is in good working order, and that you know how to use it. The best prepared PowerPoint will fail if the technology fails, or if the instructor has trouble using it. Always have a back-up plan in place!

Using Flip Charts

Flip charts, like PowerPoints, are visual aids that are used to facilitate, enhance or bring more clarity to the learning experience. It is an interactive and flexible aid that promotes interaction and engagement between the facilitator and the participants.

Flip charts promote participation as they are interactive—the facilitator can use the flip chart to write participants’ ideas or answers. They also promote flexibility in teaching and learning, since the facilitator is writing as discussion evolves and not fixed in a “set” progression. Flip charts are low-tech, inexpensive, and easily portable. They also reinforce learning because participants can see and hear what is being talked about.

Participants feel like they have contributed if the facilitator writes what the participant says. It is best to use the words the participant uses and not to paraphrase. It is necessary to remember that what gets written needs to be discussed. Filling a room with lists of things people have said without analyzing and discussing what they say does not produce real learning.

The following are tips for using the flip chart:

- Use dark marker colors, such as black, dark brown, or dark blue for the main text. Lighter colors should only be used to highlight. Using many colors on a flip chart will catch your audience’s eye.

- Print in large block letters. Do a “test” flip chart page before the workshop and make sure it can be read from the back of the room.

- Be sure not to crowd the flip chart with too much information. Only key points should be written.

- Watch your spelling. If you have problems with spelling, work on memorizing the correct spelling of words you are likely to use. But do not let spelling get in the way of using a flip chart. Creating a “spell-free” zone in the class may take some pressure off both you and the participants.

- Many facilitators prepare some flip charts in advance. Be sure to proofread any flip charts prepared in advance.

- Post pages you want participants to continue to be able to see, or pages you want to refer back to. Tear pieces of tape ahead of time to make it easier to post flip chart pages.

- Keep prepared flip charts covered with a blank page until you are ready for the class to see the page. When finished discussing a page, “flip” it over, unless you want the class to be reminded of the information.

- If possible, use flip chart paper with light, preprinted “grid” lines to help you print more legibly.

- Do not turn your back on the group and “talk to the flip chart.” Write what is needed, and then turn back to the group. A few moments of silence is okay. Do not block your audience’s view of the chart— stand to the side.

- You can, in advance, lightly pencil in reminder notes to yourself on the flip chart.

Training and Overall Program Evaluation

There are three types of training evaluation: (1) training session reaction assessments; (2) learning assessments; and (3) training impact assessments.

Evaluating Program Effectiveness

To make sure that the training program is accomplishing its goals, an evaluation of the training can be valuable. Training should have, as one of its critical components, a method for measuring the effectiveness of the training. When course objectives and content are developed for a training program, a plan for evaluating the training session(s) should be designed and integrated into the program’s other elements. An evaluation will help employers or supervisors determine the amount of learning achieved and whether a worker’s performance has improved on the job.

Among the methods for evaluating training are:

- Student opinion. Questionnaires or informal discussions with workers can help employers determine the relevance and appropriateness of the training program;

- Assessment of student learning. This can be accomplished through such activities as demonstration skills or testing.

- Supervisors’ observations. Supervisors are in good positions to observe a worker’s performance—both before and after the training—and to note improvements or changes; and

- Workplace improvements. The ultimate success of a training program may be changes throughout the workplace that result in reduced injury and illness rates.

However it is conducted, an evaluation of training can give employers the information necessary to decide whether or not workers have achieved the desired results, and whether the training session should be offered again at a future date.

Improving the program

If, after evaluation, it is clear that the training did not give workers the level of knowledge and skill that is expected, then it may be necessary to revise the training program or provide periodic retraining. At this point, it may help to pose certain questions to workers and those who conducted the training: (1) Were parts of the content already known and, therefore, unnecessary? (2) What material was confusing or distracting? (3) Was anything missing from the program? (4) What did the workers learn, and what did they fail to learn?

It may be necessary to repeat steps in the training process—that is, to return to the first steps and retrace the training process. As the program is evaluated, the employer should ask:

- If a job analysis was conducted, was it accurate?

- Was any critical feature of the job overlooked?

- Were important gaps in knowledge and skills included?

- Was material already known by the workers intentionally omitted?

- Were the instructional objectives presented clearly and concretely?

- Did the objectives state the level of acceptable performance that was expected of the workers?

- Did the learning activity simulate the actual job?

- Was the learning activity appropriate for the kinds of knowledge and skills required on the job?

- When the training was presented, was the organization of the material and its meaning made clear?

- Were the workers motivated to learn?

- Were the workers allowed to participate in the training process?

- Was the employer’s evaluation of the program thorough?

A critical examination of the steps in the training process will help employers determine where course revision is necessary.

Specific Populations to Consider

- Non-English speaking. A person’s verbal ability often tends to exceed his or her literacy levels. For best results, trainers should communicate in the native language of the participants and should provide materials in the participants’ primary language. If the trainer does not speak the trainees’ primary language, interpreters may be used. However, be sure to use a translator with trusted credentials. It is not advisable to use one worker as a translator for the others. Employ approaches similar to those used for low-literacy audiences.

- Limited English proficiency. Materials used with those who have limited English proficiency should be easy to understand or written in languages other than English. Favor those materials or curricula that encourage interaction, student input, and critical thinking. (Szudy and Gonzalez Arroyo). Consider using pictograms, visuals, and demonstrations or other methods that are non-verbal to convey information. Employ approaches similar to those used for low-literacy audiences.

- Contingent workers, day laborers and temporary workers. Employ approaches similar to those used for low-literacy or non-English speaking audiences. This will ensure maximum communication of the training content with minimum language interference. Favor visual and verbal methods over written text.

- Young Workers. Workers who are high school or college age and recent additions to the workforce require additional guidance. They may be fully able to intellectually comprehend training information, but they lack the experience that time in the workforce provides. Additional emphasis should be placed on safety and health precautions, experiential exercises and demonstrations that exhibit the inherent danger that lurks in the workplace.

Appendix A

Multilingual Resources

Below are resources to use when looking for (mostly) Spanish language safety and health material. Remember that simply translating English safety and health materials into Spanish or another language is not necessarily adequate for your target population to understand the material. There are many different terms and dialects in Spanish (and other languages) and you need to ensure that you are using the correct ones. Also, using the correct literacy level is just as important in other languages as it is in English. It is best to test the translated materials using a focus group made up of a subset of your target population.

OSHA Publications

OSHA Dictionaries (English and Spanish)

- Frequently Used Construction Industry Terms

- Frequently Used General Industry Terms

- General OSHA Terms

OSHA Publications in Spanish and Other Languages

Many OSHA publications are available in both English and Spanish, as well as Portuguese, Russian and other languages. To order multiple copies of these resources, call OSHA’s Publications Office at (202) 693- 1888 or visit OSHA’s Publications page at www.osha.gov/publications.

Adobe Reader is required to view PDF files.

OSHA Mobile-Friendly e-Books

Select OSHA publications are available in e-Book format. OSHA e-Books are designed to increase readability on smartphones, tablets and other mobile devices. For access, go to www.osha.gov/ebooks.

Susan Harwood Training Grant Products

This web site features training materials such as PowerPoint™ presentations, instructor and student manuals, and test questions developed by Susan Harwood grantees. These resources are available in multiple languages.

OSHA Safety Campaigns

OSHA’s Campaign to Prevent Heat Illness in Outdoor Workers

OSHA’s nationwide Heat Illness Prevention Campaign aims to raise awareness and teach workers and employers about the dangers of working in hot weather and provide valuable resources to address these concerns. Begun in 2011, the Heat Illness Prevention Campaign has reached more than 10 million people and distributed close to half a million fact sheets, posters, QuickCards™, training guides and wallet cards. OSHA, together with other federal and state agencies and nongovernmental organizations, spreads the word about preventing heat illness. For example, OSHA collaborates with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Weather Service to include worker safety precautions in Excessive Heat Watch, Warning, and Advisory Products.

Available on this web page are numerous resources that can be used to prevent heat illnesses:

- The Educational Resources section links to information about heat illnesses and how to prevent them. Many of these resources target vulnerable workers with limited English proficiency and/or low literacy.

- The Using the Heat Index section provides guidance to help employers develop a heat illness prevention plan.

- The Training section includes a guide to help employers and others to teach workers about heat illness. There are links to more resources in other languages.

- The Online Toolkit section includes news releases, public service announcements, drop-in articles about heat illness prevention that you can customize to share, and campaign artwork.

- The Fatality Map is an interactive infographic representing many of the heat-related fatalities that occurred outdoors between 2008 and 2014. The map provides a geographic reminder that Water.Rest.Shade. is vital to providing a safe and healthful environment when working outdoors in the heat.

The Heat Illness web page and many resources are available en español.

OSHA’s Fall Prevention Campaign

This campaign is part of OSHA’s nationwide effort to raise awareness among workers and employers about the hazards of falls from ladders, scaffolds and roofs. The educational resources page gives workers and employers information about falls and how to prevent them. There are also training tools for employers to use and posters to display at their worksites. Many of the new resources target vulnerable workers with limited English proficiency.

The Fall Prevention web page and many resources are available en español.

Fall Prevention Videos (v-Tools)

Videos are an effective educational tool. Several workplace training videos, based on true stories, examine how falls lead to death and how these fatal falls could have been prevented.

These training tools (v-Tools) explain why using the right type of fall protection equipment allows workers to return home the same way they go to work each day.

You can download the following videos in English and Spanish, read the transcripts or watch the videos on YouTube:

Falls in Construction

V-Tools on other construction hazards are also available.

OSHA State Plan Foreign Language Safety and Health Resources

State Plan Spanish language resource page

This page lists examples of Spanish language resources from OSHA state plan states. This listing also includes selected Spanish language resources from state agencies in states under Federal OSHA jurisdiction.

Other Foreign Language Safety and Health Resources

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

This site includes links to NIOSH publications in Spanish on a variety of construction topics, and also provides links to other agencies and organizations that have Spanish language resources.

Electronic Library of Construction Occupational Safety and Health (eLCOSH)

This electronic library was developed and is maintained by CPWR—The Center for Construction Research and Training—and provides a wide range of materials on construction safety and health. The goal is to improve safety and health for construction workers by making such information more accessible.

Information is available here in English, Spanish, and other languages.

Georgia Tech Spanish Language Construction Training Website

This site provides training guides in Spanish on several construction safety and health topics—scaffolding, fall protection, electricity, handling of objects/materials, and trenches and excavations. For each topic, there are educational materials in various formats, including posters, pamphlets, tailgate session guides, and formal presentations.

Labor Occupational Health Program (LOHP), UC Berkeley

This site provides training guides in English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese to assist trainers in homecare, restaurant safety, janitorial safety, agriculture and other industries.

LOHP Multilingual Resource Guide

This guide contains an extensive collection of links to worker safety and health training materials (such as fact sheets, curricula, and checklists) that are available from many sources online in languages other than English.

Occupational Health Branch, California

Department of Health Services

BuildSafe produced a safety and health tailgate training kit in English and Spanish. The kit consists of Safety Break cards that cover 23 general construction safety topics and are linked to information in the Cal/OSHA Pocket Guide for the Construction Industry. These cards are simple to use and designed to improve the quality of tailgates.

Mi Trabajo Seguro (My Safe Job)

This Spanish language web site provides safety and health information for construction workers. Developed in collaboration with the hit telenovela “Pecados Ajenos” (“Sins of Others”), this site introduces helpful construction safety information that follows a construction safety storyline on the show.

Appendix B

Program Evaluation and Quality Control Resources

Evaluation of Worker Training Programs

It is important to periodically evaluate the training program to make sure that training is effective and that programs are achieving the intended results. Evaluation should determine how well a program is implemented, how much knowledge is gained by students, and the outcomes of the training.

The following are resources and guides that can be used to create and conduct a successful evaluation and maintain quality control of the training program.

Resource Guide for Evaluating Worker Training: A Focus on Safety and Health (1997)

The Resource Guide for Evaluating Worker Training is published by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and its Worker Education and Training Program (WETP) in collaboration with the George Meany Center for Labor Studies. The goal of the Resource Guide is to ensure that workers receive safety and health training that works.

The Resource Guide presents and explores a range of successful evaluation ideas, techniques, and tools for:

- Identifying areas for program improvement;

- Measuring the short- and longer-term accomplishments of a worker training program; and

- Assessing whether, and to what extent, training has brought positive changes to the workplace.

Examples of instruments developed and used by NIEHS WETP awardees to evaluate their worker training programs are displayed throughout the Guide.

For copies of the Resource Guide, please contact the NIEHS National Clearinghouse for Worker Safety and Health Training at (202) 331-7733 or email wetpclear@niehs.nih.gov.

Evaluation Resources

UCLA-Center for the Study of Evaluation Program Evaluation Kit (1987)

The Program Evaluation Kit developed by the UCLA Center for the Study of Evaluation consists of 9 volumes of practical guidelines for designing and implementing evaluations.

- Volume 1, The Evaluator’s Handbook (provides dozens of checklists)

- Volume 2, How to Focus an Evaluation

- Volume 3, How to Design a Program Evaluation

- Volume 4, How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation

- Volume 5, How to Assess Program Implementation

- Volume 6, How to Measure Attitudes

- Volume 7, How to Measure Performance and Use Tests

- Volume 8, How to Analyze Data

- Volume 9, How to Communicate Evaluation Findings

Measuring and Evaluating the Outcomes of Training (1996)

This is a collection of research papers that was presented at the 1996 NIEHS Spring meeting on measures and evaluation of safety and health training programs.

Appendix C

References

- A Worker’s Sourcebook: Spanish Language Health and Safety Materials for Workers, University of California, Los Angeles, Labor and Occupational Safety and Health, http://www.losh.ucla.edu/losh/resourcespublications/la-fuente-obrera.html.

- Assessing Occupational Safety and Health Training: A Literature Review, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 98-145, June 1998.

- Criteria for Accepted Practices in Safety, Health, and Environmental Training, American National Standards Institute, Inc. (ANSI)/American Society of Safety Engineers (ASSE), Z490.1-2009.

- Culture, Health and Literacy: A Guide to Health Education Materials for Adults with Limited English Literacy Skills, http://healthliteracy. worlded.org/docs/culture/about.html.

- Delp, L. et al., Teaching for Change: Popular Education and the Labor Movement, UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education, 2002.

- Evaluation of the Limited English Proficiency and Hispanic Worker Initiative, U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Prepared by Coffey Consulting, December 2009.

- Immigrant Worker Safety and Health Report, from a conference on research needs, draft NIOSH scientific information disseminated for peer review, NIOSH and University of Massachusetts Lowell, April 2010.

- Minimum Health and Safety Training Criteria: Guidance for Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER), HAZWOPER-Supporting and All-Hazards Disaster Prevention, Preparedness and Response, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Worker Education and Training Program (WETP), January 2006, http:// tools.niehs.nih.gov/wetp.

- ODP Blended Learning Approach, version 1.0, ODP/DHS. November 27, 2003.

- OSHA Outreach Training Program Guidelines, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, February 2009.

- OSHA Training Standards Policy Statement, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, April 28, 2010, http://www. osha.gov/dep/standards-policy-statementmemo-04-28-10.html.

- Report from the 1999 National Conference on Workplace Safety & Health Training: Putting the Pieces Together & Planning for the Challenges Ahead, Co-sponsored by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, HHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2004-132, February 2004.

- Robson L., Stephonson C., Schulte P., Amick B., Chan S., Bielecky A., Wang A., Heidotting T., Irvin E., Eggerth D., Peters R., Clarke J., Cullen K., Boldt L., Grubb P. A systematic review of the effectiveness of training & education for the protection of workers. Toronto: Institute for Work & Health, 2010; Cincinnati, OH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2010-127.

- Szudy, Elizabeth and Gonzalez Arroyo, Michele, The Right to Understand: Linking Literacy to Health and Safety Training, Labor Occupational Health Program, University of California at Berkeley, 1994.

- Training Requirements in OSHA Standards and Training Guidelines, OSHA 2254, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 2015 (Revised).

- Wallerstein, N. and Rubenstein, H., Teaching about Job Hazards, A Guide for Workers and Their Health Providers, American Public Health Association, 1993.

Appendix D

Free On-site Safety and Health Consultation Services for Small Business

OSHA’s On-site Consultation Program offers free and confidential advice to small and medium-sized businesses in all states across the country, with priority given to highhazard worksites. Each year, responding to requests from small business owners looking to create or improve their safety and health management programs, OSHA’s On-site Consultation Program conducts over 29,000 visits to small business worksites covering over 1.5 million workers across the nation.

On-site consultation services are separate from enforcement and do not result in penalties or citations. Consultants from state agencies or universities work with employers to identify workplace hazards, provide advice on compliance with OSHA standards, and assist in establishing safety and health management programs.

For more information, to find the local On-site Consultation office in your state, or to request a brochure on Consultation Services, visit www.osha.gov/consultation, or call 1-800- 321-OSHA (6742).

Under the consultation program, certain exemplary employers may request participation in OSHA’s Safety and Health Achievement Recognition Program (SHARP). Eligibility for participation includes, but is not limited to, receiving a full-service, comprehensive consultation visit, correcting all identified hazards and developing an effective safety and health management program. Worksites that receive SHARP recognition are exempt from programmed inspections during the period that the SHARP certification is valid.

Appendix E

NIOSH Health Hazard Evaluation Program

Getting Help with Health Hazards

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is a federal agency that conducts scientific and medical research on workers’ safety and health. At no cost to employers or workers, NIOSH can help identify health hazards and recommend ways to reduce or eliminate those hazards in the workplace through its Health Hazard Evaluation (HHE) Program.

Workers, union representatives and employers can request a NIOSH HHE. An HHE is often requested when there is a higher-thanexpected rate of a disease or injury in a group of workers. These situations may be the result of an unknown cause, a new hazard, or a mixture of sources. To request a NIOSH Health Hazard Evaluation go to www.cdc.gov/ niosh/hhe/request.html. To find out more, in English or Spanish, about the Health Hazard Evaluation Program:

E-mail HHERequestHelp@cdc.gov or call 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636).

OSHA Educational Materials

OSHA has many types of educational materials in English, Spanish, Vietnamese and other languages available in print or online. These include:

- Brochures/booklets;

- Fact Sheets;

- Guidance documents that provide detailed examinations of specific safety and health issues;

- Online Safety and Health Topics pages;

- Posters;

- Small, laminated QuickCards™ that provide brief safety and health information; and

- QuickTakes, OSHA’s free, twice-monthly online newsletter with the latest news about OSHA initiatives and products to assist employers and workers in finding and preventing workplace hazards. To sign up for QuickTakes visit www.osha.gov/quicktakes.

To view materials available online or for a listing of free publications, visit www.osha. gov/publications. You can also call 1-800-321- OSHA (6742) to order publications.

Workers’ Rights

Workers have the right to:

- Working conditions that do not pose a risk of serious harm.

- Receive information and training (in a language and vocabulary the worker understands) about workplace hazards, methods to prevent them, and the OSHA standards that apply to their workplace.

- Review records of work-related injuries and illnesses.

- File a complaint asking OSHA to inspect their workplace if they believe there is a serious hazard or that their employer is not following OSHA’s rules. OSHA will keep all identities confidential.

- Exercise their rights under the law without retaliation, including reporting an injury or raising health and safety concerns with their employer or OSHA. If a worker has been retaliated against for using their rights, they must file a complaint with OSHA as soon as possible, but no later than 30 days.

For more information, see OSHA’s Workers page.

OSHA Regional Offices

Region I

Boston Regional Office

(CT*, ME*, MA, NH, RI, VT*)

JFK Federal Building, Room E340

Boston, MA 02203

(617) 565-9860 (617) 565-9827 Fax

Region II

New York Regional Office

(NJ*, NY*, PR*, VI*)

201 Varick Street, Room 670

New York, NY 10014

(212) 337-2378 (212) 337-2371 Fax

Region III

Philadelphia Regional Office

(DE, DC, MD*, PA, VA*, WV)

The Curtis Center 170 S.

Independence Mall West

Suite 740 West

Philadelphia,

PA 19106-3309

(215) 861-4900 (215) 861-4904 Fax

Region IV

Atlanta Regional Office

(AL, FL, GA, KY*, MS, NC*, SC*, TN*)

61 Forsyth Street, SW, Room 6T50

Atlanta, GA 30303

(678) 237-0400 (678) 237-0447 Fax

Region V

Chicago Regional Office

(IL*, IN*, MI*, MN*, OH, WI)

230 South Dearborn Street Room 3244

Chicago, IL 60604

(312) 353-2220 (312) 353-7774 Fax

Region VI

Dallas Regional Office

(AR, LA, NM*, OK, TX)

525 Griffin Street, Room 602

Dallas, TX 75202

(972) 850-4145 (972) 850-4149 Fax

(972) 850-4150 FSO Fax

Region VII

Kansas City Regional Office

(IA*, KS, MO, NE)

Two Pershing Square Building

2300 Main Street, Suite 1010

Kansas City, MO 64108-2416

(816) 283-8745 (816) 283-0547 Fax

Region VIII

Denver Regional Office

(CO, MT, ND, SD, UT*, WY*)

Cesar Chavez Memorial Building

1244 Speer Boulevard, Suite 551

Denver, CO 80204

(720) 264-6550 (720) 264-6585 Fax

Region IX

San Francisco Regional Office

(AZ*, CA*, HI*, NV*, and American Samoa,

Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands)

90 7th Street, Suite 18100

San Francisco, CA 94103

(415) 625-2547 (415) 625-2534

Fax

Region X

Seattle Regional Office

(AK*, ID, OR*, WA*)

300 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1280

Seattle, WA 98104

(206) 757-6700 (206) 757-6705 Fax

* These states and territories operate their own OSHA-approved job safety and health plans and cover state and local government employees as well as private sector employees. The Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, New Jersey, New York and Virgin Islands programs cover public employees only. (Private sector workers in these states are covered by Federal OSHA). States with approved programs must have standards that are identical to, or at least as effective as, the Federal OSHA standards.

Note: To get contact information for OSHA area offices, OSHAapproved state plans and OSHA consultation projects, please visit us online at www.osha.gov or call us at 1-800-321-OSHA (6742).

How to Contact OSHA

For questions or to get information or advice, to report an emergency, fatality, inpatient hospitalization, amputation, or loss of an eye, or to file a confidential complaint, contact your nearest OSHA office, visit www.osha.gov or call OSHA at 1-800-321-OSHA (6742), TTY 1-877-889-5627.

Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970

“To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.”

For assistance, contact us.

We are OSHA. We can help.

Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required.

This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627.

Safety Resource for Development and Delivery of Training to Workers

U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration OSHA 3824-08 2015

Disclaimer

This guidance document is not a standard or regulation and it creates no new legal obligations. The document is advisory in nature, informational in content, and is intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. In addition, the Act’s Section 5(a)(1), the General Duty Clause, requires employers to provide their workers with a workplace free from recognized hazards likely to cause death or serious physical harm. Employers can be cited for violating the General Duty Clause if there is a recognized hazard and they do not take reasonable steps to prevent or abate the hazard. However, failure to implement any specific recommendations contained within this document is not, in itself, a violation of the General Duty Clause. Citations can only be based on standards, regulations, and the General Duty Clause.