Inspecting Occupational Safety and Health in the Construction Industry

Summary Statement

International Labor Organization handbook is designed to help provide information and training for inspectors. It contains information on key safety and health concepts and occupational safety and health issues, including managing an inspection program and performing on-site inspections.

2009

Section 3: The construction industry and OSH

3.1 Characterization of the construction industry

3.2 Main features of the construction industry and its specific OSH features

3.3 Strategies for improving OSH in the construction industry

A brief characterization of the construction industry is given in subsection 31 together with some of the main OSH statistics. It shows that the industry is one of the main employers in many countries of the world, but also one in which a significant part of occupational accidents (especially, fatal accidents) occur.

Subsection 32 summarizes the main features of the construction industry and its OSH specificities. By showing the peculiarities of this industry, it allows a better definition of the procedures and methods for reducing accidents and professional diseases.

Finally, subsection 33 presents some of the conclusions of two important events in the European Union which may also be applied to other countries and may contribute to improve OSH in the construction industry. These conclusions are closely related to the issues and questions referred to in the previous subsection.

3.1 Characterization of the construction industry

The construction industry is one of the biggest industrial employers in many countries of the world. The ILO estimates the number of construction workers in the world at more than 110 millions1 (usually, between 5 to 10% of the world’s workforce), but in many countries double that number depend, directly or indirectly, on the construction sector.

The Confederation of International Contractors’ Associations (CICA) estimates the world production by the construction industry at 3 to 4 billions (1012) of Euros. The gross domestic product (GDP) varies, sometimes significantly, among countries, but is usually between 5% to 15%.

In most countries, construction enterprises are micro (fewer than 10 workers), small (10 to 49 workers) or medium (50 to 249 workers) in terms of the number of workers they employ. In some regions (e.g. the European Union), the average number of workers per enterprise is estimated at 5 or 6. About one third of the workers are employed in micro-enterprises and almost two thirds in small or medium-size enterprises. Large enterprises (250 or more workers) employ a small number of workers.

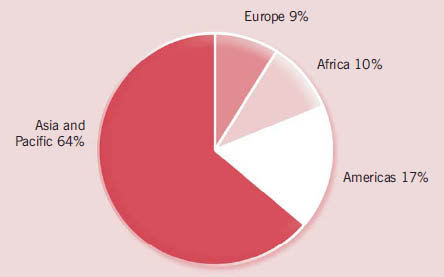

The ILO estimates the number of fatal occupational accidents in the construction industry at about 60 000 every year [Valcárcel, 2003] with about 64% in the Asia and Pacific region, 17% in the Americas, 10% in Africa and 9% in Europe (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Distribution of the fatal accidents in the construction industry

In many countries, there are twice as many occupational accidents leading to more than 3 days’ absence in the construction industry as the proportion of construction workers to all industrial workers would lead us to expect, and three times as many fatal accidents (Figure 6).

Figure 6 – Accidents in the construction industry versus all industries

3.2 Main features of the construction industry and its specific OSH features

The increasing competition among construction companies brings out the need to pay more attention to construction productivity issues.

The main objectives of any construction project are to avoid any negative environmental impact, to build with quality (avoiding defects), to ensure safety and health (avoiding occupational accidents and diseases), to meet the deadline and to minimize costs (Figure 7).

Figure 7 – The main elements/objectives to take into account in a construction project

Achieving these five objectives is very complex, in view of the inter-relationships among them and the pressure of the market to favour some of them (traditionally, cost and time) over those more related to society as a whole (environment, safety and health, and quality). There is, however, a strong belief that occupational safety and health should never be compromised in any circumstances, for social and human reasons.

The construction industry has changed in recent decades. Today, many of those involved in the construction process recognize the positive influence on productivity of good occupational safety and health. In other words, they recognize that prevention measures are an investment rather than a cost.

Studies in European Union countries and elsewhere have shown that the cost of occupational accidents is about double the cost of measures that would prevent them (European Commission, 2003) (Figure 8). These prevention measures consist of action during the design, the planning and the execution of the construction project.

Figure 8 – Prevention costs versus occupational accidents costs

The construction industry is a hazardous industry. This statement has been repeatedly used by people involved in the construction process, to explain, at least in part, the high number of accidents and professional diseases in the industry. Meanwhile, more and more of them have been questioning the efficiency and the effectiveness of the existing systems for implementing and monitoring safety and health measures. However, all of them agree that if an accident happens, something has failed.

On the other hand, construction professionals know the hazards and the corresponding preventive measures; and in many cases those measures are being taken in most countries. Meanwhile, accidents continue to happen, although in some regions and countries there have been significantly fewer accidents (especially fatal accidents) in the last few decades.

This means that, in many cases, prevention measures are not being taken to “force” the bigger cut in the number of accidents that everyone wishes to see. In most countries, there are enough laws and regulations on OSH in construction, yet there is a failure to implement these laws and regulations. In view of this, some questions are:

(i) Why are the existing laws and regulations not implemented in many cases?

(ii) Why are prevention measures not implemented in many cases?

There is no single answer to these questions. Many arguments have been used to justify the non-implementation of existing laws and preventive measures. These include:

- the high number of existing OSH laws and regulations (sometimes more than 100), and the fact that they are prescriptive rather than performance-based;

- the OSH laws and regulations need adjusting to take into account the peculiarities of the construction industry (see below);

- the OSH laws and regulations keep changing, sometimes in a short period;

- the initial costs of prevention measures are high (failing to recognise how they benefit productivity and consequently on reducing costs);

- labour inspectors need to be more proactive and even reactive (failing to recognise that it is not possible to have an inspector for each construction site).

Moreover, the specific nature of the construction industry means that there is a need for tailor-made OSH laws and regulations. This, however, can never justify failure to implement the national laws and regulations or to take preventive measures. The specific features of this industry include:

- producing unique products (a building, a bridge, a road, etc.) unlike most other industries, which turn out products in series (usually making workplaces easier to control, although sometimes they, too, are complex, as in the chemical industry and others);

- many parties being involved in the different phases of a construction project, sometimes with different interests: owners (low cost, high quality); users (high quality of life, comfort); designers (aesthetics, structural safety); contractor and subcontractors (reduce costs, improve productivity); etc. (Do they all think about safety and health?);

- a high number of subcontractors (and their subcontracting chain) in construction projects, making the enforcement and inspection of OSH legislation, as well as the running of OSH training programmes, more difficult;

- construction companies more and more becoming “management and coordination companies” (outsourcing all or most of the construction works);

- subcontractors being the main employers (most of them are micro or small enterprises);

- being a labour-intensive activity (although often highly mechanized) ;

- “labour-only” subcontracting and self-employment on short-term contracts being common practice;

- payment on the basis of “work performed” (rather than hourly-based) becoming the most frequent method of payment in many countries (“favouring” a high number of working hours per day and working days per week);

- the highest rate of fatal and non-fatal accidents (in many countries sometimes more than 50% of all accidents in all industries);

- falling from height as the main cause of fatal accidents in most countries (sometimes more than 50% of fatal accidents in construction).

The governments and social partners in each country should reflect more deeply on all these features and, together, look for possible solutions at both the legislative level and the implementation level. It is the author’s belief that OSH legislation should be as simple as possible, and be as performance-based as possible (i.e. not too prescriptive), so that it is easy to implement by contractors and to inspect by labour inspectorates. Moreover, the owners/clients of the construction projects should be more involved in OSH issues.

3.3 Strategies for improving OSH in the construction industry

The issues referred to in the previous subsection have led many countries and regions to discuss ways to improve OSH in the construction industry. The European Union has seen two relevant events on these issues in recent years, the conclusions of which may also be applied elsewhere. The two events were held in 2004 and 2006 by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, based in Bilbao, Spain.

The main conclusions of the “European Construction Safety Summit” held in 2004 were published as the “Bilbao Declaration” (EASHW, 2004). They may be summarized as follows:

- Procurement - building in safety: OSH issues are integral to the construction project process. They are not confined to the construction phase of a project but occur throughout the entire lifetime of the project: design, construction, maintenance and demolition.

- Enforcement - improving compliance: Prevention is the guiding principle for OSH legislation in the European Union.

- Guidelines - sharing good compliance practice: OSH legislation needs to be accompanied by guidelines that can help to explain how the legal requirements can be implemented and in this way share good compliance practice.

- Designing safe and healthy construction work: this declaration calls on the design community in the European Union countries to design out risk wherever reasonably possible and to highlight any remaining residual risk in all projects.

- Improving safety and health performance through social partner commitment: Social dialogue and agreements on OSH improvements are key tools to ensure the indispensable commitment to real improvements in safety and health in construction workplaces.

- A final decision related to follow-up: all the signatories of the Bilbao Declaration were to meet again two years later. The follow-up meeting took place in September 2006, when the main conclusions were as follows (EASHW, 2006):

- The industry has made considerable effort to improve occupational safety and health, by working in cooperation with each other. The work done demonstrates what can be achieved by working together. Further improvements can only be achieved by collaborative effort with contractors, large and small, working together with the workers, architects, designers, engineers and surveyors. However, as discussed at the event they need help from outside.

- Procurement: the public sector should be exemplar procurers. Without the public sector setting these standards, how can private clients be influenced? More guidance is needed with leadership demonstrated at the highest level, and a shift away from simple applying “lowest cost” judgements.

- Enforcement: some delegates stressed the lack of consistency in enforcement. This leads to companies who apply the best standards, being unsuccessful with bids for tenders, and in many cases not even bidding, as they know it is a foregone conclusion that they will be unsuccessful. Sharing good practice requires those companies who use it, to operate in all Member States. These good practices can then spread to subcontractors and others and there should not be a different OSH regime over a border in a single market.

- OSH Statistics: work needs to be done to enable accurate comparisons between Member States.

- Over the last two years, following the European Construction Safety Summit, the European construction industry has made significant progress in improving safety, health and welfare. Now action is required to achieve change and to make a real and lasting impact on safety and health on Europe’s construction sites. This action is not just by the industry partners, continuing to work together, but by the others highlighted above - the regulators, the clients and information providers.

In addition, some countries and regions have made many changes to their OSH legislation in a search for continual improvement of the working conditions of construction workers and for fewer occupational accidents and less occupational diseases in this industry.

In some cases, these changes aim to comply with ILO Convention No. 167 (1988) on “Safety and Health in Construction”, which introduced a new approach to improving OSH in construction. The main features of this important Convention are summarized in section a), below. An example of this ILO approach in European Union countries is summarized in section b). Some recommendations which could improve OSH in the construction industry are made in section c).

a) The ILO approach to improving OSH in construction (ILO Convention No. 167)

ILO Convention No. 167 (Safety and Health in Construction) has five sections: (i) scope and definitions; (ii) general provisions; (iii) preventive and protective measures; (iv) implementation; (v) final provisions. Of these, the general provisions (Figure 9) are the most important for the present document. The associated ILO Recommendation No. 175 helps us to understand and to interpret the Convention.

Figure 9 – The main general provisions of the ILO Convention 167

Member States that ratify Convention No. 167 should enact the necessary laws to make these provisions or adapt existing laws to accommodate them. Highlights of these general provisions are:

- The need to nominate a “Principal Contractor” or “Person” (physical or legal);

- the need for those involved in the design and planning of a construction project (e.g. managers and designers) to take OSH into account;

- the OSH of those who will be involved in the maintenance of the project should also be taken into account during the use or operation phase.

The “Principal Contractor” (not necessarily the general/main constructor, but certainly one of the constructors that know the construction process) or the “Person” (i.e. a competent person as defined in the Convention, who should have the authority and means to carry out his/her mission), should be responsible for coordination of the prescribed OSH measures and for ensuring compliance with such measures.

The legislation for this new “stakeholder” in the construction industry may be simple as regards construction projects where there is a general/main constructor, who may be appointed as “Principal Contractor”. However, where more than one constructor is involved, simultaneously or successively, or in construction projects where a “Person” (other than the genral/main constructor or any of the constructors) is to be appointed, the legislation should stipulate which of the constructors should be appointed as “Principal Contractor” (in the meaning of the Convention) and/or the qualification (including the basic education, training, experience) of such a “Person”.

OSH should also be made the responsibility of those involved in the design and planning of a construction project, namely the project or construction managers and designers (not only of the construction project as the final product, but also of the temporary structures that are needed to build it, like scaffoldings, formworks, guardrails, and other). This means that the managers and designers should answer questions like the following:

- How should the project be physically built while avoiding or minimizing the risks to the construction workers?

- How much time is needed to build the project (and each of its parts) while reducing the risk from too many workers in the same workplace or from tasks that may cause risks when performed at the same time?

For this purpose, the new OSH legislation should be inserted into the existing construction legislation on the responsibilities of managers and designers. The importance of this responsibility for OSH of those involved in the design and planning phases (i.e. before starting the execution phase) was illustrated by a study in the European Union in the 1980s, which concluded that more than 60% of fatal accidents in the construction industry could have been avoided by action before launching the construction site (Figure 10).

As for the maintenance of the construction project, the OSH should also be of concern, especially to designers, who should answer questions like the following:

- How can the construction project be maintained without putting at risk the workers involved in its maintenance?

- Exactly where (which parts?), when (which periodicity?) and how (e.g. means of access to the parts) should maintenance take place?

Although the Convention refers expressly to cleaning and painting, other issues should also be considered, for example inspection of the construction project, including the equipment (e.g. air conditioning) installed in it.

Figure 10 – Causes of fatal occupational accidents in construction

b) The European Union approach to improving OSH in construction (EU Directive 92/57/EC)

One example of the ILO approach embodied in Convention No. 167 is the new methodology adopted by the European Union, which is summarized below.

Because the European Union (EU) recognized that construction was a highly hazardous industry, in 1992 it published a special Directive2 (EU Directive No. 92/57/EC of June 1992) that changed the way safety and health in construction was seen. This Directive is now known worldwide as the Construction Sites Directive (CSD). Since then, the construction industry has changed in all countries of the European Union, and safety and health in construction is now an issue that most construction stakeholders are aware of and care about.

The high number of meetings, seminars, congresses and symposia organized since then in the EU countries has contributed significantly to this awareness. Despite this, there are still some stakeholders in some EU countries who continue to ignore their responsibilities for construction safety and health, especially owners and designers who traditionally held the view that safety and health on construction sites was the sole responsibility of the contractors. The official entities (governments and, in particular, labour inspectorates) should boost the awareness of these stakeholders through seminars related to their specific duties.

Since its publication, each country of the EU has brought the provisions of the CSD into national law. However, although some countries have made this Directive work by creating the mechanisms and means for effective implementation, others have made a “simple” transposition with few adaptations to their own situation, thereby sometimes creating confusion for those who must implement it or check its application every day. Other countries still have changed, or are changing, their first transposition, clarifying it and/or adding detail. In spite of the common base introduced by the CSD, the fact is that each country in the EU has its own approach.

Before the CSD was published in the European Union, the responsibility for the implementation of all prevention measures on construction sites was handed mainly (and in some countries, only) to the contractors, based on the legislation and/or on the contracts between the owners and those contractors. After the publication of the Directive, all those involved in the construction process (owners, designers, managers, supervisors, contractors, subcontractors and workers) have responsibilities and obligations for occupational safety and health matters.

The CSD introduced a new approach to the improvement of OSH in construction. It highlighted the importance of prevention measures (managerial and material) to reduce work-related accidents and diseases in construction. It took the provisions of ILO Convention No.167 on “Safety and Health in Construction” (1988) into account. In short, the approach of the CSD is based on (Figure 11):

(i) the principle that all those involved in the construction process have specific roles and responsibilities concerning OSH, including the owner/client and designer;

(ii) the new concept of safety and health coordination (for the design phase and for the construction phase), creating:

- two new stakeholders in the construction process (safety and health coordinators for the design phase and for the construction phase) and;

- three new documents concerning hazard prevention (the prior notice, the safety and health plan, and the safety and health file3).

Figure 11 – The European Union approach (Directive 92/57/EEC)

The OSH roles of all those involved in the construction process, the new concept of safety and health coordination (both during the design phase and during the construction phase) and the new documents concerning hazard prevention are often described elsewhere and so lie beyond the scope of this document. However, some of the concepts and documents are referred to in this document, but in summary form.

c) Recommendations on improving OSH in the construction industry

Taking into account the approaches mentioned in a) and b) above, and the experience of countries that already take them, a possible strategy for promoting and improving an effective OSH culture in the construction industry based on ILO values is summarised in Figure 12.

Figure 12 – A possible strategy for promoting and improving OSH in the construction industry

To improve OSH in the construction industry, the following steps are strongly recommended:

- Ratify ILO Convention No. 167 on safety and health in construction, taking into consideration the provisions of ILO Recommendation No. 175.

- Create and/or adapt the national laws and regulations on OSH to accommodate the provisions of the Convention (taking into account the associated Recommendation and the ILO Code of Practice published in 1992), by:

-

(i) setting out the rules for appointing the Principal Contractor and/or Person in charge of OSH issues during the design and planning phase and during the execution phase, stating whether they should be physical or legal persons;

(ii) specifying the qualifications of the Principal Contractor and/or Person in charge of OSH, be they physical or legal persons (in the latter case, they should involve a number of competent physical persons);

(iii) implementing OSH training programmes for the physical persons in charge of OSH issues;

(iv) promoting separate OSH training programs for each of the main stakeholders in the construction process, including representatives of the owners/clients, project and construction managers, designers (architects, engineers of the different specialities of the final product and of the temporary structures), OSH experts, etc.;

(v) establishing levels of requirements according to the size and complexity of the main types of construction projects (e.g. based on any existing classification of construction projects);

(vi) planning the implementation of the new laws and regulations by phases, i.e. fixing the appropriate periods of time for them to come into force and effectively applied, starting with the largest construction projects and ending to the smallest ones (the implementation of new technical laws or regulations to come into force immediately and for all construction projects is strongly discourage). - Give priority to performance-based (instead of prescriptive) laws and regulations for technical legislation, namely that concerning the preventive and protective provisions, including details and examples of their implementation in mandatory and/or informative annexes for interpretation and clarification purposes; in some countries, the mandatory annexes have been established by the social partners in the construction industry;

- Hold separate meetings with the main owners (or with their associations, if they exist), the main associations of constructors and the main construction unions, in order to promote the implementation of the new laws and regulations, while making clear the responsibilities, competences, duties and rights of each of these groups;

- Implement tailored guidelines for OSH-MS in the construction industry based on ILO-OSH 2001 Guidelines (ILO, 2001a) and a public-based recognition system for construction enterprises wishing that their systems be recognised in a voluntary basis. The creation of incentive systems for those enterprises that implement and recognise their systems would be a good strategy. The implementation of an OSH-MS in a construction project will help the enterprises to comply with the laws and regulations more easily and systematically, while facilitating the task of those who have the duty of verifying compliance with such laws and regulations (OSH experts, labour inspectorates, etc.).

_________________________________________

1 Murie, Fiona (2007) from the International Federation of Building andWood Workers, a federation of about 350 unions, states that the number of construction workers in the world is estimated at 180 million and the number of fatal accidents in this industry at 100 000 every year.

2 An EU Directive is an instrument (like a law) which is legally binding on every Member State of the European Union as regards the results to be achieved, but it needs to be transposed to the national law of each country, so it is up to each country to establish the way and means by which to achieve the results.

3 The Prior Notice announces the opening of a new construction site, whereas the Safety and Health Plan and the Safety and Health File aim to identify and prevent hazards, the former during the construction phase and the latter during the maintenance phase.