OSHA Can Better Respond to State-Run Programs Facing Challenges

Summary Statement

OSHA carries out enforcement directly in 34 states and

territories, while the remaining 22 have chosen to administer their own enforcement programs. GAO was asked to review issues related to state-run programs. This report is the result. It examines (1) what challenges states face in

administering their safety and health programs, and (2) how OSHA responds to state-run programs with performance issues. GAO found that states have difficulty filling vacant inspector positions, obtaining training for inspectors, and retaining qualified inspectors. Recruiting inspectors is difficult due to the shortage of qualified candidates, relatively low state salaries, and hiring freezes. Although OSHA has taken steps to make its courses more accessible to

states, obtaining inspector training continues to be difficult.

GAO recommended that Congress consider giving OSHA a mechanism to expedite assistance to states experiencing

challenges. In addition, GAO recommended that OSHA

facilitate access to training, establish time frames for resuming enforcement if states do not address challenges in a timely manner, and document lessons from its past

experiences in resuming federal enforcement of state-run programs.

April 18, 2013

GAO

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters

April 2013

WORKPLACE SAFETY AND HEALTH

OSHA Can Better Respond to State-Run Programs Facing Challenges

This Report Is Temporarily Restricted Pending Official Public Release.

Highlights of GAO-13-320, a report to congressional requesters

Why GAO Did This Study

OSHA is generally responsible for setting and enforcing occupational safety and health standards in the nation’s workplaces. OSHA carries out enforcement directly in 34 states and territories, while the remaining 22 have chosen to administer their own enforcement programs (referred to as state-run programs) under plans approved by OSHA. GAO was asked to review issues related to state-run programs. This report examines (1) what challenges states face in administering their safety and health programs, and (2) how OSHA responds to state-run programs with performance issues. GAO reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations and OSHA policies; conducted a survey of 22 state-run programs; and interviewed officials in OSHA’s national office, all 10 OSHA regions, and from a nongeneralizable sample of 5 state-run programs; and interviewed labor and business associations and safety and health experts.

What GAO Recommends

Congress should consider giving OSHA a mechanism to expedite assistance to states experiencing challenges. In addition, OSHA should take a number of actions, including facilitating access to training; establishing time frames for resuming enforcement if states do not address challenges in a timely manner; and documenting lessons from its past experiences in resuming federal enforcement of state-run programs. In response, OSHA agreed with the recommendations and said it will explore ways to implement them.

View GAO-13-320. For more information, contact Revae Moran at (202) 512-7215 or moranr@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

State-run programs face several challenges that primarily relate to staffing, and include having constrained budgets, according to OSHA and state officials. States have difficulty filling vacant inspector positions, obtaining training for inspectors, and retaining qualified inspectors. Recruiting inspectors is difficult due to the shortage of qualified candidates, relatively low state salaries, and hiring freezes. Although OSHA has taken steps to make its courses more accessible to states, obtaining inspector training continues to be difficult. According to an agency official, OSHA’s Training Institute faces several challenges in delivering training, including recruiting and retaining instructors, difficulty accommodating the demand for training, and limitations in taking some courses to the field due to the need for special equipment and facilities. These challenges are further exacerbated by states’ lack of travel funds, which limit state inspectors’ access to OSHA training. Retaining qualified inspectors is another challenge among states. Officials noted that, once state inspectors are trained, they often leave for higher paying positions in the private sector or federal government. GAO’s survey of the 22 state-run programs that cover private and public sector workplaces showed that turnover was more prevalent among safety inspectors than health inspectors. Nearly half of these states reported that at least 40 percent of their safety inspectors had fewer than 5 years of service. In contrast, half of the states reported that at least 40 percent of their health inspectors had more than 10 years of service. These staffing challenges have limited the capacity of some state-run programs to meet their inspection goals.

OSHA has responded in a variety of ways to state-run programs with performance issues. These include closely monitoring and assisting such states, such as accompanying state staff during inspections and providing additional training on how to document inspections. OSHA has also drawn attention to poor state performance by communicating its concerns to the governor and other high-level state officials. In addition, OSHA has shared enforcement responsibilities with struggling states or, as a last resort, has resumed sole responsibility for federal enforcement when a state has voluntarily withdrawn its program. Although OSHA evaluates state-run programs during its annual reviews, GAO found that OSHA does not hold states accountable for addressing issues in a timely manner or establish time frames for when to resume federal enforcement when necessary. In addition, the current statutory framework may not permit OSHA to quickly resume concurrent enforcement authority with the state when a state is struggling with performance issues. As a result, a state’s performance problems can continue for years. OSHA officials acknowledged the need for a mechanism that allows them to intervene more quickly in such circumstances. GAO also noted that OSHA does not compile lessons learned from its past experiences when it has resumed federal enforcement in a state. This prevents the agency from building on previous experiences in responding to future situations.

Contents

- Letter

- Background

- The Primary Challenges Affecting States’ Ability to Administer Their Occupational Safety and Health Programs Relate to Staffing

- OSHA Has Responded in Various Ways to States with Performance Issues, but It Lacks an Established Time Frame for Resuming Federal Enforcement When Needed

- Conclusions

- Matter for Congressional Consideration

- Recommendations for Executive Action

- Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

- Appendix I: GAO Survey of the State-Run Programs

- Appendix II: Staffing Levels for State Safety and Health Inspectors, Fiscal Years 2012 and 2013

- Appendix III: Salary Ranges for Federal and State Safety and Health Inspectors, 2012

- Appendix IV: Comments from the Department of Labor

- Appendix V: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

- Related GAO Products

- Figure: Figure 1: Map Showing Whether OSHA or the State Provides Occupational Safety and Health Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2012

Abbreviations

- FAME: Federal Annual Monitoring Evaluation

- OSH Act: Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970

- OSHA: Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- OTI: OSHA Training Institute

April 16, 2013

The Honorable George Miller

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Joe Courtney

House of Representatives

States are facing severe budget constraints that have jeopardized their ability to effectively administer state-run occupational safety and health programs. In addition, from January 2008 through June 2009, Nevada experienced 25 workplace fatalities, raising concerns about the way Nevada and other states with their own state-run safety and health programs administer them. The Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is generally responsible for setting and enforcing employer compliance with occupational safety and health standards in the nation’s workplaces under the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act).1 The OSH Act also permits states to assume responsibility for setting and enforcing their own safety and health standards by submitting a state plan to OSHA for approval.2 Currently, 22 states have chosen to administer their own OSHA-approved occupational safety and health programs that cover workers in the private sector as well as workers in the state and local public sector.3 The other states rely on OSHA to enforce compliance with federal safety and health standards, which apply to employees in the private sector, but not those in the state and local public sectors.

Under the OSH Act, OSHA is required to monitor state-run programs and withdraw approval of a state’s program if it finds that the state has failed to comply substantially with any provision of its state plan, including those required by the federal statute and regulations.4 A state may voluntarily withdraw its program for any reason, such as lack of political support. However, a state’s inability to effectively operate its program can create gaps in protection for workers in the state and place a burden on OSHA if federal intervention is required. In response to your request that we review worker protection in states that face challenges administering their own safety and health programs, this report examines (1) challenges states face in administering their safety and health programs, and (2) how OSHA responds to state-run programs with performance issues.

To address our objectives, we reviewed applicable federal laws and regulations and OSHA policies related to the administration of state-run programs. We interviewed officials from OSHA’s national office and all 10 OSHA regional offices about how the agency monitors selected aspects of state-run programs and responds to states’ performance issues and how OSHA prepares for potential state-run program withdrawals. We reviewed the 22 state-run programs that cover both private sector and state and local public sector workers. To better understand the challenges faced by states, we interviewed officials from a nongeneralizable sample of five states selected to illustrate a range of program performance: California, Hawaii, Nevada, South Carolina, and Washington. We interviewed state officials in person in California, Hawaii, Nevada, and Washington, and by phone in South Carolina. To gather the perspectives of OSHA regional officials, we visited two regional offices and two area offices—Region 9 in San Francisco and the region’s area offices in Honolulu and in Las Vegas, and Region 10 in Seattle. We visited Region 9 because it oversees three of the states we selected for review— California, Hawaii, and Nevada—and Region 10 because it oversees one of the states we selected—Washington. We also interviewed regional administrators and other managers in the remaining eight regional offices by phone. In addition, we discussed state-run programs with representatives of labor and business organizations; the Occupational Safety and Health State Plan Association, which represents the interests of states with state-run programs; and academic experts in safety and health.5

To gather additional information about the states with state-run programs that cover both private sector and state and local public sector workers, we surveyed state officials in the 22 states with these programs and obtained responses from all of them. We requested information about their sources of state funding, state occupational safety and health standards, the experience levels of their inspectors, and the perceived likelihood of the withdrawal of their state plan in the near future. See appendix I for more information on our survey of the state-run programs.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2011 to April 2013 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The OSH Act was enacted to ensure safe and healthful working conditions, in part by providing for the adoption and enforcement of federal occupational safety and health standards and by assisting and encouraging states to adopt programs of their own. OSHA develops and enforces federal safety and health standards under the OSH Act. In addition, OSHA reviews, approves, and evaluates the plans and operations of states that have chosen to operate their own occupational safety and health programs.6 According to OSHA, benefits of state-run occupational safety and health programs include coverage of state and local public sector workplaces, the resources provided by states to supplement federal resources, familiarity with local working conditions and industries, and the innovative approaches states can provide.

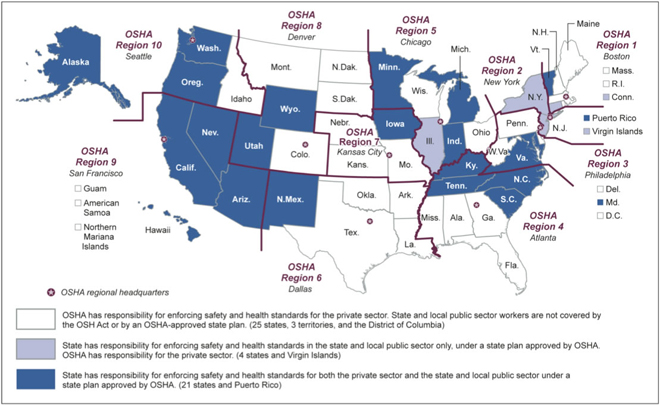

State-run programs vary in their scope of coverage and division of enforcement authority between OSHA and the state. A state-run program may define its scope of coverage according to the type of workplace or worker, within certain limits. For example, a state may exclude private contractors on military bases. However, all state-run programs are required to cover state and local government (public sector) workers in the state. Figure 1 shows the states without a state-run program, for which OSHA provides enforcement for private sector workplaces; the states with state-run programs that cover only the public sector, for which OSHA provides enforcement for private sector workplaces; and the 22 states we reviewed with state-run programs that cover both private and public sector workplaces.7

Figure 1: Map Showing Whether OSHA or the State Provides Occupational Safety and Health Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2012

Note: In all states, OSHA generally has authority to conduct safety and health inspections of federal agencies. With some exceptions, federal agencies are generally responsible for maintaining their own occupational safety and health programs, consistent with OSHA’s regulations.

Selected Requirements of State-Run Programs

Occupational Safety and Health Standards

The OSH Act requires that state-run programs provide for the development and enforcement of safety and health standards that are “at least as effective” in providing safe and healthful employment as the federal standards.8 States may adopt standards that are identical to OSHA’s, or that are different from, but determined by OSHA to be at least as effective as, OSHA’s standards. This may include state standards that are more stringent or that address hazards not covered by federal standards. Seventeen of the 22 state-run programs we surveyed reported that they had established state standards that are substantively different from OSHA’s standards or that cover hazards for which there are no corresponding federal standards. (See the responses to survey question 4 in app. I for information on state standards reported by state-run programs.)

Staffing and Training

The OSH Act and OSHA regulations require state-run programs to employ a sufficient number of qualified and adequately trained personnel necessary for the enforcement of safety and health standards.9 Personnel who enforce occupational safety and health standards include safety officers (hereafter referred to as safety inspectors) and industrial hygienists (hereafter referred to as health inspectors). (See app. II for information on staffing levels for state safety and health inspectors.) Enforcement activities include inspecting worksites, typically on a schedule that reflects the relative risks among industries, testing workplace conditions such as occupational noise and air quality, documenting workplace hazards, investigating accidents and complaints, and issuing citations and penalties for violations. OSHA’s Directorate of Training and Education administers OSHA’s national training and education policies and procedures. One of OSHA’s directives details the training program for federal safety and health inspectors and requires state-run programs to establish their own training programs for their safety and health inspectors that are at least as effective as OSHA’s training program.10 OSHA officials told us that all states, including those that have developed their own training programs, may also avail themselves of training courses offered by the OSHA Training Institute (OTI). OTI, the agency’s national training center near Chicago, conducts training courses for both federal and state safety and health inspectors. Officials from several states told us that their state-run programs train their inspectors through a combination of courses taught in-house and by OSHA at OTI.11 In addition, OTI’s Education Centers—a network of non- profit organizations throughout the mainland United States and in Puerto Rico—deliver occupational safety and health training to state and local public and private sector workers, supervisors, and employers. These Education Centers rely on tuition, rather than financial assistance from OSHA, to fund their training, according to an OTI official.

Funding

The OSH Act also requires each state-run program to provide adequate funds for the administration and enforcement of the state’s occupational safety and health program.12 (See states’ responses to survey question 1 in app. I for information on sources of state funds.) The size and cost of state-run programs vary. When a state initially submits its plan to OSHA for approval, OSHA reviews the state’s proposed budget to ensure it is reasonable and complete. The budget forms the baseline funding level for that state, according to OSHA officials. Subsequently, each state-run program applies annually to OSHA for federal grant funds of up to 50 percent of this baseline amount, which is subject to the availability of appropriated funds. The state must match the federal grant funds received.13

Approval of State-Run Programs

OSHA approves the state plans and reviews the operations of state-run safety and health programs. The first step in the process, initial approval, begins by obtaining OSHA approval for a developmental plan whereby a state must assure OSHA that, within 3 years, it will have in place the necessary elements for an effective occupational safety and health program. Once a state has completed and documented all of its developmental steps, it is eligible for certification whereby OSHA attests to the structural completeness of the plan. At least 1 year following certification, during which OSHA monitors the program’s operations, the state may become eligible for final approval. For at least the first 3 years after initial approval, OSHA retains discretionary enforcement authority and may enforce federal standards to the extent necessary to assure occupational safety and health. OSHA may grant a state-run program final approval if it determines, on the basis of actual operations, that the program meets the criteria specified in the OSH Act and OSHA’s regulations. By granting a state plan final approval, OSHA relinquishes exclusive enforcement authority to the state in areas covered by the plan.14 Currently, 15 of the 22 states’ programs have been granted final approval by OSHA, while the agency has granted the remaining 7 states’ programs initial approval.

OSHA may withdraw approval of a state-run program entirely and resume sole enforcement responsibility if the state fails to comply substantially with the provisions of its plan.15 In state-run programs with initial approval status, OSHA retains concurrent enforcement authority and may directly enforce federal safety and health standards in those states.16 However, before OSHA can reassume concurrent enforcement authority in a state- run program with final approval status, the program must be returned to initial approval status, either by the state voluntarily giving up its final approval status, or by OSHA revoking final approval of the state’s plan.17

Monitoring of State-Run Programs

State-run occupational safety and health programs are monitored by OSHA’s national office, its 10 regional offices and the regions’ area offices. In the national office, the Directorate of Cooperative and State Programs oversees the grants provided to state-run programs. OSHA regional and area offices work directly with states to set inspection goals, taking into account staffing and funding levels in each state. The regional and area officials review state-run program performance reports and meet with state officials to monitor their progress toward meeting their inspection goals. OSHA’s regions also conduct reviews of each state-run program called Federal Annual Monitoring Evaluation (FAME) reviews. These reviews cover several areas related to state performance, such as inspections and staffing, and can also include on-site case file reviews of the state program.18 OSHA’s Directorate of Cooperative and State Programs examines the results of the FAME reviews and other reports on mandated state activities, according to OSHA officials.

Regional and area officials also meet quarterly with state managers to review states’ performance. During these quarterly meetings, OSHA regional and area officials review several types of reports that compare a state’s progress across multiple performance measures with federal and national data for the same period. OSHA officials told us that the national office stays in contact with the regions through regularly scheduled meetings and other contacts, as needed, to discuss any state program issues. Regions generally elevate any issues to the national level, as needed. For example, regional officials will contact the national office about early warning signs of a challenged state program, such as decreases in staffing levels or not meeting performance goals.

The Primary Challenges Affecting States’ Ability to Administer Their Occupational Safety and Health Programs Relate to Staffing

States face several challenges that affect their ability to adequately staff their state-run occupational safety and health programs, including finding staff to fill vacant inspector positions, retaining qualified inspectors, and obtaining necessary training for their inspectors. The budget shortfalls that many of the states face and their human resource policies can contribute to these staffing challenges, which have also limited some states’ ability to meet their inspection goals.

Difficulty Filling Vacant Inspector Positions

According to officials from OSHA’s national office, four regional offices, and several state-run programs, filling vacant inspector positions is a key challenge for states due, in part, to the shortage of job candidates with the necessary qualifications such as a bachelor’s degree, technical expertise, and a sufficient level of experience to independently carry out inspections. OSHA officials in Region 4 said state-run program officials in their region prefer to hire health inspectors with a health-related bachelor’s degree, preferably in chemistry or biology, although such a degree is not required. Officials with California’s state-run program said it can be difficult to recruit candidates with expertise in fast growing industries such as biotechnology—a specialty that would be particularly helpful for a growing number of worksites—or candidates with fluency in more than one language. In addition, the director of Hawaii’s state-run program said that, when the program needed to hire 13 inspectors in 2012, too few applicants with the desired level of experience applied; consequently, the job announcement was modified to consider applicants with no prior experience.

Filling vacant inspector positions is also difficult due to relatively low state salaries and limited opportunity for salary increases. Officials from state- run programs told us that state salaries for inspectors are generally lower compared to those offered by the private sector or federal government, even though a 1980 OSHA report on state-run program requirements stated that salary levels for state inspectors should be competitive enough to attract and maintain a fully qualified inspection staff.19 (See app. III for salary ranges for federal and state safety and health inspectors.) The starting point of the salary scale for entry level staff averaged $39,413 in 2012 for safety inspectors in all state-run programs.20 OSHA officials said that, in contrast, federal inspectors are typically hired at the midpoint of the salary scale, which ranged from $38,511 to $47,103 in 2012. Officials from Nevada’s state-run program said that some applicants turned down employment interviews with the state after learning the starting salary. In addition, 6 of the 22 states we reviewed (Arizona, Indiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Vermont, and Wyoming) have a general salary system that does not allow staff to progress to higher salary levels, which further contributes to their difficulty in attracting applicants, according to OSHA officials.

Some state-run programs have attempted to address the issue of inspector pay by revising their compensation policies to allow for higher salaries, but they have had mixed success with their policies. For example, officials from South Carolina’s state-run program said that they raised their salaries to try and reduce staff turnover. In contrast, according to OSHA officials in Region 8, Utah tried to raise inspector salaries for its state-run program, but the state government did not approve the state officials’ request. While OSHA officials said that they cannot directly address the issue of low salaries for state personnel, they told us OSHA surveyed state-run programs on their 2012 salary levels to help identify disparities in salaries between state and federal inspectors, so that state- run programs could provide this information to their respective legislatures when requesting salary increases.

States’ constrained budgets and human resource policies can also contribute to challenges in recruiting qualified inspectors.21 OSHA officials in Region 4 told us that constrained state budgets had previously resulted in furloughs in two of the states with state-run programs in their region: Kentucky and Tennessee. OSHA officials in Region 10 also told us that state-wide pay cuts and furloughs have contributed to staffing challenges in the state-run programs in their region: Alaska, Oregon, and Washington. Further, in an effort to decrease costs to the state, Nevada’s governor issued a directive in 2010 imposing a hiring freeze and reducing or eliminating certain pay increases for state employees. In addition, OSHA’s 2011 FAME report on Nevada’s state-run program noted that the state legislature imposed a 2.5 percent wage reduction for all state employees in July 2011.22 OSHA officials from several regions and one state-run program said that state-wide hiring freezes have prevented some state-run programs from filling vacant positions, including California, Michigan, and New Mexico. Such state-wide policies are outside the control of state-run programs because they affect personnel across all state programs.

Difficulty Retaining Inspectors

Officials in 7 OSHA regions and the 4 states we contacted identified staff turnover as a challenge to administering state-run programs. According to agency officials, once a state provides its inspectors with training, they become more marketable and often leave for higher paying positions in the private sector and with federal OSHA. For example, according to OSHA officials in Region 10, staffing levels in Alaska’s state-run program declined by 54 percent from fiscal years 2009 to 2011 as state inspectors left to work for oil companies.

In addition, our survey of the 22 state-run programs that cover both public and private sector workplaces showed that, as of the end of calendar year 2011, turnover was more prevalent among safety inspectors than health inspectors. Specifically, almost half of the states (10 of 22) we surveyed reported that 40 percent or more of their safety inspectors had fewer than 5 years of service in their roles. In contrast, half (11 of 22) of the states we surveyed reported that 40 percent or more of their health inspectors had more than 10 years of service. While turnover was less prevalent among health inspectors, state-run programs are comprised mostly of safety inspectors: there were close to twice as many safety inspectors (667) than health inspectors (369), based on OSHA data for fiscal year 2012. (See responses to survey question 2 in app. I for information on the average years of service for state safety and health inspectors.)

According to OSHA and state officials, one result of high turnover is that states regularly invest money and time training new staff on introductory courses—the higher the turnover, the greater the resource investment. In addition, officials from Nevada’s state-run program noted that, in the absence of high turnover, the state program’s resources could have been spent on other high priority needs, such as providing advanced courses for experienced inspectors. Finally, OSHA officials from Region 9 said that the three state-run programs in their region that face difficulty recruiting and retaining staff (Arizona, Hawaii, and Nevada) may end up having to return to OSHA any unspent federal funds that had been associated with salaries for these positions.

Difficulty Obtaining Training for Inspectors

Some states’ inspection staff have difficulty obtaining the training needed to conduct effective inspections and enforce compliance with safety and health standards because of challenges OTI faces in delivering training and because of state restrictions on travel. The challenges OTI faces include:

- Difficulty recruiting and retaining instructors. OTI uses multiple instructors in each course, including contractor staff, to provide training to state inspectors. Over the past 5 years, OTI contract instructor expenditures have been reduced by about two-thirds, according to an OTI official. The official also noted difficulty with recruiting enough instructors with adequate experience and that there was high turnover due to retirements and transfers to other positions within the agency.

- Difficulty accommodating demand. In fiscal years 2009 and 2010, OSHA hired about 150 additional federal inspectors, according to an OTI official, who also noted that the number of inspectors from state- run programs registering for OTI courses increased. As a result of the rise in newly hired federal and state inspectors, training demand greatly increased at a time when OTI’s resources were reduced, according to an OTI official. As a result, some OTI courses are in high demand and short supply and fill up quickly. For example, an OSHA official said Nevada has had difficulty enrolling staff for OTI’s whistleblower course given that the waiting list is a year long.23 According to OTI, additional courses cannot be scheduled quickly given that its training schedules are developed 6 to 18 months in advance.

- Limited capacity for webinars. Although OSHA inquired whether OTI could double the frequency of its webinars from once a month to twice per month, OTI officials told us they could not because of staff capacity and the number of technology licenses they currently hold. Furthermore, OTI officials said that there will be limited development of new online courses because they have started a 5-year process of revising their online courses.

- Limits on offering certain courses in the field. OTI has a limited number of courses it can bring to states with state-run programs. According to OSHA, the courses increasingly use site visits and workshops that are more difficult to set up in the field. Much of the training OTI provides to state inspectors is hands-on training given on- site in the five laboratories contained in its building: (1) construction, (2) hazardous materials, (3) small equipment (such as woodworking machinery), (4) heavy equipment (such as power presses), and (5) industrial hygiene. According to OSHA officials, few states have the equipment and laboratories needed to support providing training off- site.

In addition to the challenges OTI faces, states also face challenges in sending staff to OTI for training. According to regional and state officials, some state inspectors have difficulty travelling to OTI, especially in recent years, because states have had limited travel funds, including freezes on out-of-state travel as part of state-wide austerity measures.

In response to the difficulties states have faced in funding travel, OTI has taken steps to make its courses more accessible, such as:

- Taking courses to the field when feasible. State-run programs may request that OTI courses be brought to them, provided the states can pay for OTI staff’s travel expenses. OTI officials told us that they will take a course to a state if instructors are available, scheduling is feasible, and hands-on components and workshops can be transported. OTI also considers whether required training facilities and equipment are available in the field. However, they also said they will not take a course to a state unless a minimum number of participants are scheduled to attend. When OTI agrees to take a course to a state, it takes 6 to 12 months from the date of the state’s request to schedule a course, according to OTI. In fiscal year 2012, OTI held five courses for state inspectors on-site in four states.24 In fiscal year 2013, OTI plans to conduct six courses for state inspectors in six states.25

- Accommodating urgent training needs. An OTI official acknowledged that required courses for newly hired inspectors typically have waiting lists, and in response they have accommodated state-run programs that demonstrated an urgent training need by allowing staff in these states to enroll before staff in other states.26 For example, OTI gave priority enrollment to new state inspectors in Hawaii following a hiring surge in 2012.

- Sharing electronic training materials. OTI also periodically sends electronic materials for mandatory courses to all state-run programs and for other courses to states upon request, according to an OTI official.

- Surveying state training needs. Every year, OTI surveys state-run programs to gauge their training needs based on actual and planned numbers of safety and health staff. The survey also solicits the level of interest in certain training topics and courses. OTI uses this information to plan and schedule its training courses for the coming year.

Despite OTI’s efforts to make training more accessible to state-run programs, officials and experts told us that high staff turnover, combined with constrained state budgets, has hurt states’ ability to ensure they have adequately trained inspectors. Consequently, states have leveraged the expertise of other states and OSHA regions to meet their own training needs in a more cost-efficient manner. An OTI official told us that when OTI could not bring a refinery course to Washington at the state’s request, a trainer from the state-run program in California traveled to Washington to help the state of Washington conduct the course and was reimbursed by the Washington state program for travel. In addition, according to the administrator of Hawaii’s state-run program, two of the state’s newly hired health inspectors were sent to California to accompany experienced state inspectors on inspections. Similarly, when Hawaii’s new hires travelled to OTI for training, they received in-person mentoring by accompanying inspectors from OSHA’s Region 5 area offices on inspections, according to an OSHA official. Some states located near OTI’s Education Centers have sent their inspectors to these centers to obtain needed training. Unlike training provided by OTI, courses completed at these centers do not count toward OSHA’s mandatory inspector training requirements described in its training directive; however, some states have sent inspectors to a nearby center to save travel costs and obtain training. An OTI official noted that, although Education Center courses place less emphasis on OSHA standards and enforcement, they provide training on hazard recognition and abatement. OTI Education Centers are not authorized to deliver courses on conducting inspections.

Another resource available to states to facilitate information sharing and obtain training in lieu of traveling to OTI is the library of state training materials posted on OSHA’s website. The website also allows state inspectors to access other states’ online training resources.

Staffing Challenges Affect Some States’ Ability to Meet Their Inspection Goals

OSHA’s annual reviews of state-run programs show that staffing challenges have limited the capacity of some state-run programs to meet their inspection goals. For example, in its 2011 FAME review of Arizona’s state-run program, OSHA found that the state conducted 913 inspections—65 percent of its inspection goal of 1,400 inspections for that year. OSHA noted that one of the reasons the state did not meet its goal was the number of staff who were capable of performing inspections on their own.27 Similarly, in its 2011 FAME review of Nevada’s state-run program, OSHA found that the state conducted 1,254 inspections in fiscal year 2011—59 percent of its goal of 2,132 inspections. An OSHA official noted that the state completed 1,203 inspections in fiscal year 2012—63 percent of its goal of 1,900 inspections. Nevada’s challenges have persisted, even though the state matched its federal OSHA grant of $1,505,900 and provided an additional $3,450,003 and $3,886,951 in 100 percent state funding in fiscal years 2011 and 2012, respectively. State officials attributed the state’s inability to meet its inspection goals to high staff turnover, which necessitated diverting experienced inspectors from conducting inspections to training and mentoring new staff. The state officials added that having fewer experienced staff meant that they could not conduct as many programmed (scheduled) inspections as they would have liked because they were required to respond to higher priorities, such as situations that involved imminent danger, fatalities, and complaints. As a result, according to an OSHA official, the number of programmed inspections the state completed comprised about 17 percent of the total inspections (199 of 1,203) completed in fiscal year 2012.28 According to Nevada officials, they are aware of the challenges in completing inspections, but they told us they are limited in their ability to address high inspector turnover. Nonetheless, OSHA urged Nevada in its 2011 FAME report to work with the state legislature to increase inspector salaries and explore other available options that may affect staff retention.

OSHA Has Responded in Various Ways to States with Performance Issues, but It Lacks an Established Time Frame for Resuming Federal Enforcement When Needed

OSHA Has Responded in a Variety of Ways to States Having Difficulty Meeting Their Performance Goals

When OSHA identifies issues in state-run programs, such as when they are having difficulty meeting their inspection goals, OSHA has responded in a variety of ways. OSHA’s responses may include recommending corrective action by states to address performance issues; increasing its monitoring activities; providing extra training and technical assistance to state program staff; communicating with the governor or other high-level state officials about poor performance; sharing joint enforcement responsibility with the state; and, as a last resort, withdrawing OSHA’s approval of the program and resuming sole federal enforcement. OSHA officials told us they prefer to work collaboratively with states using a graduated approach—providing guidance and support before taking any higher level actions.

OSHA must be prepared to step in quickly to resume responsibility for enforcement if a state voluntarily withdraws its program. OSHA officials told us that they rely on their contact with states to obtain advance notice and status updates about any potential voluntary withdrawals of state programs.29 Officials in all 10 OSHA regions told us that, as of June 2012, no state other than Hawaii was at high risk of voluntarily withdrawing its state program within the next 3 years. Nevertheless, in states facing budget constraints, the state may consider budget cuts that could result in discontinuing the state’s occupational safety and health program, requiring OSHA to resume safety and health enforcement in the state. For example, in 1987, when the governor of California discontinued funding for the state’s occupational safety and health program covering private sector employers, OSHA had to quickly resume this enforcement responsibility. OSHA provided this enforcement coverage until 1989, when the state resumed private sector enforcement activities.30 We previously reported on both of these situations.31 (See responses to survey question 3 in app. I for information on legislative or administrative actions affecting state-run programs.)

The following examples illustrate the various methods OSHA has used to respond to state-run programs with issues.

Nevada - OSHA recommended corrective action

OSHA has been closely monitoring Nevada’s state-run program since 2009, when a number of fatalities in the construction industry in the state raised concerns about the adequacy of the state’s safety and health program. OSHA recommended that Nevada address issues in meeting its state performance goals, including re-evaluating the state’s inspection goals and modifying them, if appropriate, to reflect changes in policy and declining industries in the state, pursuing all available options to increase the salaries of state inspectors, and providing clear guidance for organizing the state’s case files. In addition, OSHA asked the state to specify in its fiscal year 2014 grant application a goal for the number of programmed inspections it plans to conduct. An official from OSHA’s Region 9 told us they continue to monitor the state closely. The official said the office is also considering accompanying state staff during inspections to get a first-hand account of how the state conducts and documents inspections.

Vermont - OSHA recommended corrective action and increased monitoring, provided extra training, and communicated with high-level state officials

In the 2011 FAME report, OSHA identified persistent issues in Vermont’s program due to the failure of program management and staff to understand or follow OSHA’s policies, procedures, and basic inspection and investigatory techniques. The report also cited a lack of training and supervision provided by state officials. In response, OSHA’s Region 1 officials said they plan to enhance their monitoring of the state’s program to ensure compliance with OSHA policies and procedures, including reviewing randomly selected inspection files and all investigations of whistleblower complaints. Also, the Region will review all cases involving worker fatalities before they are closed. In addition, regional officials told us they have been closely monitoring the state’s performance through regular phone calls and visits, and that they also provided additional training to state inspectors, such as training on how to document inspections and investigate whistleblower complaints. OSHA’s regional staff also arranged for on-site training of state inspectors by OTI because of the state’s restrictions on out-of-state travel, according to OSHA officials. For example, OTI conducted the safety and health management class, which is required by the state plan for all new inspectors, in Burlington, Vermont. In addition, OSHA Region 1 officials met with the Vermont state labor commissioner to discuss their concerns about the state-run program’s performance.

Hawaii - OSHA recommended corrective action, increased monitoring, provided extra training, communicated with high-level state officials, and shared enforcement with the state

OSHA’s response to the challenges Hawaii has faced in running its state- run program illustrates the graduated approach OSHA can take to help a state address its challenges, beginning with recommending corrective action to address issues identified through its monitoring of the state-run program, notifying the governor about the state’s continued poor performance, and developing an agreement to share enforcement with the state. Due to a lack of political support in Hawaii in 2009, funding and staffing for the state’s safety and health program were cut roughly in half, resulting in the state’s failure to complete required inspections and meet other key performance goals. One official from OSHA’s Region 9 said he has had frequent contact with the state and involved OSHA’s national office when problems persisted. Because the state had not adequately addressed its performance problems, in September 2010, OSHA elevated the issue by sending a letter to the governor expressing concerns about poor program performance. Over the next year and a half, OSHA exchanged letters with two successive Hawaii governors and the director of the state-run program, offering enforcement assistance if the state voluntarily suspended its final approval status. According to OSHA officials, the state was reluctant to give up its final approval status because Hawaii was the first state to obtain this status and it was a source of state pride.32 Hawaii state officials said that they preferred the autonomy provided under final approval status. An OSHA official noted that the business and labor communities were also concerned about the state having to relinquish final approval status, in part because of confusion over who would have jurisdiction over which workplace. An official from the Hawaii state-run program said that the state would have preferred obtaining OSHA’s assistance without giving up its final approval status. Nevertheless, Hawaii notified OSHA of its decision to do so in February 2012 in order to obtain OSHA’s assistance with enforcement. In September 2012, after several months of negotiations, OSHA and Hawaii finalized an agreement that specified the division of enforcement responsibilities between OSHA and the state; stipulated that OSHA would assist with recruiting, retaining, and training of state inspectors; and established time frames for the state to resume sole enforcement authority.33

North Carolina - OSHA recommended corrective action, increased monitoring, and shared enforcement with the state

In September 1991, a fire at a chicken processing plant in Hamlet, North Carolina, killed 25 workers. OSHA responded by quickly reasserting concurrent enforcement jurisdiction with the state the following month.34 Because the state’s occupational safety and health plan had not been granted final approval, OSHA was able to reassume federal enforcement activity without first following the procedural requirements for revoking final approval or asking the state to voluntarily give up its final approval status. In addition, OSHA issued a special evaluation report on North Carolina’s state-run program in January 1992, finding significant issues and giving the state 90 days to take corrective action. OSHA maintained an enforcement presence until it determined that North Carolina had taken sufficient corrective action, such as increasing funding and staffing for its program. Because the state plan had not yet been granted final approval status at the time of the incident, OSHA was able to expediently intervene and conduct certain enforcement activities while the state rebuilt its program. OSHA suspended concurrent jurisdiction in 1995, following a series of evaluations that documented the state’s substantial progress in improving safety and health enforcement.35

South Carolina - OSHA recommended corrective action, increased monitoring, and shared enforcement with the state

In June 2011, South Carolina enacted a law to require that all whistleblower complaints received by the state-run program from employees in the private sector be referred to the federal Department of Labor, eliminating any remedy under state law for such complaints.36 OSHA informed the state of its responsibility under the OSH Act to continue its whistleblower program. OSHA’s 2011 FAME report stated that South Carolina no longer met federal requirements for approval of its state-run program because it did not provide these workers with whistleblower coverage. Officials from OSHA’s national office and Region 4 told us that they worked with South Carolina program staff to have the legislature restore the state’s whistleblower program. In June 2012, South Carolina amended the law, authorizing the state agency to investigate private sector whistleblower complaints and pursue legal remedies for violations in state court. Regional officials told us that they plan to closely monitor the state’s whistleblower program as it is restored to ensure that the state is adequately screening and responding to complaints.

OSHA Lacks a Time Frame for Resuming Federal Enforcement in States with Performance Issues

OSHA regional officials consult with the national office when responding to state-run programs with performance issues, according to OSHA officials, and the agency may withdraw approval of a state-run program and resume federal enforcement if a state fails to comply substantially with any provision of its state plan. However, officials told us there is no specific point at which OSHA would consider withdrawing approval of a state-run program, or changing a state’s status from final to initial approval so that OSHA can resume concurrent enforcement responsibility.37 Officials in OSHA’s national office and some of its regions said there is usually a pattern of problems with a state’s performance over time that alerts them to issues with the state-run program. OSHA’s national office told us the regions will notify them far in advance about poor performance that could signal consideration of withdrawing a state- run program’s approval.

While OSHA evaluates state-run programs as part of its annual reviews, it does not hold states accountable for developing and implementing plans to address issues within a prescribed period. In accordance with the OSH Act, state-run programs must provide for the development and enforcement of safety and health standards that are at least as effective in providing safe and healthful employment as the federal standards.38 In March 2011, the Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General reported that OSHA lacks a definition of effectiveness and measures to evaluate the effectiveness of state-run programs.39 In particular, the report stated that OSHA lacks measures to quantify the effect of state-run programs on occupational safety and health. The report added that OSHA needs to define when state-run programs would be deemed performance failures, to serve as a basis for using its ultimate authority to withdraw approval of a state program. In addition, for states with final approval status, OSHA cannot step in and conduct enforcement activities because it lacks the statutory authority to do so unless the state voluntarily withdraws its plan entirely, OSHA withdraws approval of the state’s plan, or the state is returned to initial approval status, either voluntarily or by OSHA, consistent with the procedures in its regulations. However, revoking final approval can be a time-consuming process that could entail certain notice and hearing procedures if a state does not immediately agree to give up its final approval status. Under these circumstances, staffing challenges and other issues can affect states’ performance for years. OSHA officials acknowledged the need for a mechanism to more quickly intervene in state-run programs with final approval status and performance issues.

Furthermore, while OSHA has had experience in resuming enforcement in states with state-run programs, the agency does not compile lessons learned from these experiences to inform its future responses. OSHA national officials told us they would meet with the regions to discuss lessons learned when it steps in to resume enforcement in a state, but they do not find it useful to document these conversations, including capturing details such as questions raised, problems faced, options available to respond to the state’s challenges, or the type and amount of federal resources required to resume federal enforcement in the state.

Organizations can benefit by learning from past experience and adapting their practices based on what is learned. In OSHA’s case, although every situation involves different circumstances in each state, knowledge of prior OSHA responses to challenges faced by state-run programs provides guideposts for the agency to consider as it designs strategies to respond to future situations. More specifically, knowledge of the results, challenges, and unintended consequences of past federal responses can inform its deliberations as agency officials determine whether and how to intervene in response to states facing challenges in the future.

According to government standards for internal controls, agencies should assess and manage the risks they face.40 This includes having mechanisms in place to anticipate, identify, and react to risks that can affect the achievement of goals and objectives. Internal control standards also state that agencies should record information related to external and internal events and communicate it to management. However, OSHA’s lack of documentation of its experiences in resuming enforcement in states with challenged state-run programs and sharing these documents across the agency leaves the agency vulnerable to gaps in institutional knowledge, particularly with turnover of OSHA staff due to retirements, office transfers, or other attrition. During our discussions about OSHA’s recent response to the challenges faced by Hawaii’s state-run program, an OSHA regional official said that capturing the details of Hawaii’s situation and OSHA’s response would be beneficial in providing OSHA with concrete steps to follow if faced with a situation with another state in the future.

Resuming OSHA Enforcement Can Reduce State-Run Programs’ Scope and Strain Federal Resources

When resuming enforcement in a state, OSHA may not be able to devote the same level of staff resources and conduct as many inspections as the state would have conducted, according to OSHA officials. Also, when OSHA takes over enforcement, state and local public sector workers may lose the safety and health enforcement coverage that only state-run programs can provide. Furthermore, OSHA has authority to enforce only federal standards, not state-specific standards, which can be more stringent than federal standards or provide protections for hazards not covered by federal standards.

The level of resources required from OSHA to provide enforcement depends on various factors such as the number of employers and workers in a state, the number and type of industries, the location and staffing of existing OSHA offices, the scope of enforcement coverage to be provided by OSHA, and the current performance of the state-run program, according to OSHA officials. For example, OSHA officials in Region 4 told us that Kentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee have more heavy industry than South Carolina, so those states would require a larger number of OSHA staff to provide adequate enforcement. When California—the largest state-run program—ceased private sector enforcement in 1987, OSHA temporarily sent about one-third of its federal inspectors and supervisory staff to California and reassigned staff from other activities to ensure continued coverage nationwide. More recently, an OSHA official told us that in assisting Hawaii in rebuilding its state-run program, the agency plans to pay travel expenses for federal inspectors who will be assigned to work with state inspectors on a 60-day rotational basis over a 3-year period from fiscal years 2013 through 2015.41 The costs to OSHA of staff travel, renting office space, acquiring supplies, and providing equipment are projected to be about $1.5 million over a 4-year period from fiscal years 2012 through 2015. Some of the federal funds not matched by Hawaii will be redirected to support OSHA assistance to the state-run program.

To provide needed staffing for a state-run program considering withdrawal, OSHA might be able to use federal staff already in a nearby regional or area office, reassign staff from another region on a temporary basis, or hire new staff. According to OSHA officials, the agency would use a short-term response immediately after a state withdraws to respond quickly to cases such as worker fatalities, and would then arrange for more permanent staffing in the long term. According to its regional officials, OSHA has experience in adjusting its resources temporarily to respond to emergencies and changes. For example, in 2011, after the Midwest was hit by a devastating tornado, OSHA’s Region 7 had staff in place to oversee occupational safety and health during recovery work the next day. However, when OSHA resumes enforcement in a state, the reallocation of resources could affect the agency’s ability to maintain enforcement and other activities in the states for which OSHA has primary enforcement responsibility. When OSHA provided enforcement in California, OSHA’s inspection volume nationwide was generally maintained, but some other activities were disrupted, including its monitoring of other state-run programs.

Conclusions

OSHA has noted that state-run occupational safety and health programs can be beneficial to workers because of the additional types of workers covered, the familiarity states have with local working conditions and industries, and the innovative approaches states can provide in addressing safety and health hazards. In addition, these programs can be cost- effective for the federal government because of the resources states provide that supplement federal resources. However, when states face challenges in administering their programs, it can lead to performance issues which, if not addressed in a timely manner, may persist and result in inadequate safety and health protection for workers.

OSHA cannot resolve many of the root causes of states’ staffing challenges because it does not control how states set their compensation policies, but the agency ultimately remains responsible for protecting the safety and health of workers in those states and can take steps to support them in addressing their challenges. When these steps are not adequate to address states’ performance issues, it is imperative that OSHA hold states accountable for developing concrete plans that address their specific challenges and performance issues, and if necessary, step in quickly to shore up the state-run programs so that they are at least as effective as the federal program. OSHA’s ability to intervene quickly, however, depends on whether states have obtained final approval for their state-run programs because it does not have the authority to conduct enforcement in states with final approval without having the state agree to voluntarily relinquish its final approval status, revoking the state’s final approval status, or withdrawing approval of the state plan entirely, all of which can be very time-consuming processes, some of which could also entail certain notice and hearing procedures. Moreover, OSHA is cautious about reassuming concurrent enforcement authority in states with final approval status given the resources required for OSHA to do so, including devoting the time of its inspectors and setting up operations in the state. Equipping OSHA with additional tools for intervening more quickly in such situations could expedite its ability to provide assistance to challenged states without jeopardizing the safety and health of workers. In addition, OSHA has had experience in resuming federal enforcement of state-run programs and, while circumstances may differ from one state to the next, not documenting lessons learned could leave the agency without the critical institutional knowledge needed to respond to situations in the future.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

Congress should consider amending the Occupational Safety and Health Act to provide a mechanism for OSHA to more quickly intervene in state- run occupational safety and health programs with final approval status, as appropriate, to expedite federal OSHA assistance when necessary to ensure adequate enforcement of those programs that are experiencing challenges.

Recommendations for Executive Action

To better assist states in ensuring they have sound occupational safety and health programs, we recommend that the Secretary of Labor direct the Assistant Secretary for Occupational Safety and Health to take steps to help address challenges that have posed long-standing risks to states with state-run occupational safety and health programs in training staff to administer their programs. These steps could include leveraging existing federal and state resources to develop more effective and efficient ways to access and deliver training, such as partnering with OTI’s Education Centers and systematically coordinating opportunities for newly hired state inspectors to obtain on-the-job training, such as by shadowing experienced inspectors from OSHA or other state-run programs.

We also recommend that the Secretary of Labor direct the Assistant Secretary for Occupational Safety and Health to identify states with challenges that need to be addressed and require those states to develop timely plans for addressing their challenges, and if such plans are not developed, to establish time frames for when OSHA would resume sole or concurrent federal enforcement responsibility for the state-run program. This process should be tailored to the state’s unique circumstances.

Finally, to better position the agency to respond to states facing challenges, we also recommend that OSHA document lessons learned from its experiences in assisting states with their enforcement responsibilities and resuming federal enforcement of state-run programs.

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to the Secretary of Labor for review and comment. We received written comments from OSHA, which are reproduced in their entirety in appendix IV. OSHA acknowledged the major staffing challenges that state-run programs face and agreed with our recommendations. In particular, OSHA noted it has taken steps to help address states’ training challenges and will explore more effective and efficient ways to access and deliver training. Furthermore, OSHA pointed out that it will continue to use a variety of strategies to ensure that the states successfully and quickly address their challenges. However, the agency cited resource limitations, legal obstacles, and states’ unique circumstances as factors that limit its ability to move quickly to resume federal enforcement responsibility. In addition, OSHA welcomed the recommendation to document lessons learned and cited it as instrumental in providing insight for future instruction and guidance to regions and states. Finally, OSHA provided technical comments which we incorporated into the report, as appropriate.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Labor, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staffs have any questions concerning this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7215 or moranr@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Key contributors to this report are listed in appendix V.

Revae Moran, Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

1 Pub. L. No. 91-596, 84 Stat. 1590, codified as amended at 29 U.S.C. §§ 553, 651-78.

2 Although OSHA refers to states with approved state plans as “state-plan states,” in this report we refer to them as “state-run programs.” Under the OSH Act, “state” is defined to include the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. See 29 U.S.C. § 652(7).

3 Although the OSH Act does not apply to state and local public sector employers, states that operate a state-run program are required to cover state and local public sector workers. Five additional states (Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, and the Virgin Islands) have OSHA-approved programs that cover state and local public sector workers only; OSHA provides enforcement for the private sector in these states. Our report does not include these states because their programs are not comparable to those of the other state-run programs.

4 29 U.S.C. § 667(f).

5 We selected organizations, academic experts, and stakeholders for interviews based on the recommendations of OSHA officials and other experts versed in OSHA and labor issues.

6 To receive initial approval, state plans must meet certain criteria specified in the OSH Act and OSHA’s regulations. Once OSHA has determined that the operations of a state-run program meet the requirements of the OSH Act, including the development and enforcement of state standards that are at least as effective as the federal standards, it may grant the state final approval and exclusive enforcement authority. See generally 29 U.S.C. § 667, 29 C.F.R. pts. 1902, 1952, and 1956.

7 As noted previously, the OSH Act defines “state” to include Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, so the 22 state-run state programs we reviewed include those in 21 states and Puerto Rico.

8 29 U.S.C. § 667(c)(2). OSHA’s regulations further specify various “indices of effectiveness” that OSHA will use in making this determination. 29 C.F.R. § 1902.4.

9 29 U.S.C. § 667(c)(4), 29 C.F.R. §§ 1902.3(h), 1956.10(g).

10 OSHA, “Initial Training Program for OSHA Personnel”, Directive number 01-00-018 (August 6, 2008).

11 OSHA officials stated that training for state-run program staff is provided at no charge at OTI.

12 29 U.S.C. § 667(c)(5).

13 Section 23(g) of the OSH Act authorizes grants to states to assist them in administering and enforcing their state-run programs. The federal share may not exceed 50 percent of the costs of the state-run program. 29 U.S.C. § 672(g). Some states may choose to provide additional state funding beyond the amount they provide to match the federal grant.

14 29 U.S.C. § 667(e).

15 In addition to determining that a state has failed to comply substantially with its plan, OSHA must also follow certain notice and hearing procedures in order to entirely withdraw approval of a state-run program. 29 U.S.C. § 667(f), 29 C.F.R. pt. 1955.

16 OSHA may enter into an operational status agreement with states that have initial approval, in which OSHA agrees to suspend the exercise of some or all of its concurrent enforcement authority. Such an agreement may need to be modified before OSHA resumes enforcement.

17 When a state-run program is granted final approval status, OSHA’s enforcement authority is statutorily suspended and OSHA has no authority to conduct enforcement in areas covered by the state plan. Withdrawing final approval and returning the state to initial approval status reinstates concurrent federal enforcement authority. OSHA’s regulations require certain notice and hearing procedures to withdraw a state’s final approval status. 29 C.F.R. §§ 1902.47-1902.53.

18 For more information on OSHA’s monitoring activities, see GAO, Workplace Safety and Health: Further Steps by OSHA Would Enhance Monitoring of Enforcement and Effectiveness, GAO-13-61 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 24, 2013).

19 Report to the Court, AFL-CIO v. Marshall, No. 74-406, 1980 WL 29284 (D.D.C. Dec. 17, 1980). OSHA prepared this report in response to a federal court order directing OSHA to define staffing and funding levels necessary for a fully effective state-run program. See AFL-CIO v. Marshall, 570 F.2d 1030 (D.C. Cir. 1978).

20 Based on OSHA’s 2012 survey of salaries in state-run programs.

21 For more information on the effect of the most recent recession on state budgets, see GAO, State and Local Governments: Knowledge of Past Recessions Can Inform Future Federal Fiscal Assistance, GAO-11-401 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 31, 2011).

22 During an October 2009 oversight hearing before the U.S. House Committee on Education and Labor, the administrator of the Nevada state-run program said that the state would have to dedicate resources toward improving the pay structure and noted that the state legislature had created a subcommittee to pursue this issue. In its 2011 FAME review of Nevada, OSHA noted that its recommendation to increase staff salaries was the only open recommendation remaining from its 2009 special study of Nevada. Subsequently, the governor acknowledged the difficulty in recruiting and retaining experienced and qualified inspectors by including a 10 percent pay increase for safety inspectors in the state’s budget request for fiscal years 2013-2015.

23 OSHA is responsible for enforcing the “whistleblower protection” provisions of a variety of federal laws, including the OSH Act. These provisions generally prohibit employers from discriminating against employees for taking certain actions protected by these laws. In January 2009, GAO reported that OSHA faces two key challenges in administering its whistleblower program—it lacks a mechanism to adequately ensure the quality and consistency of investigations, and many investigators lack certain resources they need to do their jobs, including training. See GAO, Whistleblower Protection Program: Better Data and Improved Oversight Would Help Ensure Program Quality and Consistency, GAO-09-106 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 27, 2009). Similarly, in August 2010, GAO reported that OSHA has struggled to provide its whistleblower investigators with the skills and resources they need to effectively do their jobs. See GAO, Whistleblower Protection: Sustained Management Attention Needed to Address Long-standing Program Weaknesses, GAO-10-722 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 17, 2010).

24 In fiscal year 2012, the five courses were (1) demolition (Washington); (2) Environmental Protection Agency’s health and safety course (Utah); (3) evaluation of safety and health management systems (Vermont); (4) maritime and longshoring (Virginia); and (5) OSHA’s technical assistance for emergencies (Utah).

25 In fiscal year 2013, the six courses are (1) applied welding principles (Washington); (2) concrete, forms, and shoring (Iowa, Nevada, and Washington); (3) permit-required confined space entry (Arizona, California, and Iowa); (4) cranes and rigging safety for construction (South Carolina); (5) fall arrest systems (Arizona and Nevada); and (6) cranes and materials handling for general industry (Iowa).

26 According to OTI, courses with consistent waiting lists include initial compliance, legal aspects and inspection techniques, and investigative interviewing.

27 Arizona exceeded its inspection goal in fiscal year 2012. According to officials from OSHA Region 9, the state-run program completed 1,138 inspections—103 percent—of its goal of 1,103 inspections after adding staff and improving training.

28 An OSHA official said that programmed inspections are considered to be more effective and efficient in reaching high hazard industries and establishments than just focusing on complaint inspections. Complaint inspections will not always lead to the high hazard areas.

29 OSHA’s regulations provide that a state may voluntarily withdraw its plan by notifying OSHA in writing, setting forth the reasons for the withdrawal, and providing a letter terminating the state’s grant application. 29 C.F.R. § 1955.3(b).

30 See California State Plan; Resumption of Concurrent Federal Enforcement, 52 Fed. Reg. 21,952 (June 10, 1987) and California State Plan, 55 Fed. Reg. 28,610 (July 12, 1990).

31 GAO, OSHA’s Resumption of Private Sector Enforcement Activities in California, GAO/T-HRD-88-19 (Washington, D.C.: June 20, 1988) and Occupational Safety and Health: California’s Resumption of Enforcement Responsibility in the Private Sector, GAO/HRD-89-82 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 17, 1989).

32 Hawaii obtained final approval status in 1984.

33 See Hawaii State Plan for Occupational Safety and Health, 77 Fed. Reg. 58,488 (Sept. 21, 2012).

34 Termination of Operational Status Agreement for North Carolina State Plan, 56 Fed. Reg. 55,192 (Oct. 24, 1991). OSHA terminated its existing operational status agreement with North Carolina and reinstituted federal enforcement in certain areas, such as responding to safety and health and whistleblower complaints.

35 North Carolina State Plan; Suspension of Limited Concurrent Federal Enforcement, 60 Fed. Reg. 12,416 (Mar. 7, 1995). North Carolina subsequently received final approval status in 1996. North Carolina State Plan; Final Approval Determination, 61 Fed. Reg. 66,593 (Dec. 18, 1996).

36 The OSH Act prohibits employers from discriminating against employees for taking certain actions protected under the act, and requires OSHA to investigate whistleblower complaints and pursue legal remedies for violations in court. 29 U.S.C. § 660(c). OSHA regulations require states with state-run programs to enact state whistleblower laws that are at least as effective as the federal law to protect employees from discrimination. 29 C.F.R. § 1977.23. Although, by law, OSHA retains jurisdiction over whistleblower complaints in state-run programs, in practice it refers complaints it receives to the appropriate state-run program.

37 OSHA’s regulations describe the general circumstances that are cause for initiating withdrawal proceedings. For example, “Where a State over a period of time consistently fails to provide effective enforcement of standards,” or “Where a State fails to comply with the required assurances on a sufficient number of qualified personnel and/or adequate resources for administration and enforcement of the program.” 29 C.F.R. § 1955.3(a).

38 29 U.S.C. § 667(c)(2).

39 U.S. Department of Labor Office of Inspector General-Office of Audit, OSHA Has Not Determined If State OSH Programs Are at Least as Effective in Improving Workplace Safety and Health as Federal OSHA’s Programs, 02-11-201-10-105 (Washington, D.C.: March 2011).

40 See GAO, Internal Control Standards: Internal Control Management and Evaluation Tool, GAO-01-1008G (Washington, D.C.: August 2001).

41 Federal inspectors assigned to Hawaii include both safety and health inspectors. According to an OSHA regional official, in the first year, OSHA will provide three safety inspectors and one health inspector; in the second year, OSHA will provide two safety inspectors and one health inspector; and, in the third year, OSHA will provide one safety and one health inspector.

Appendix I: GAO Survey of the State-Run Programs

To learn about sources of state funding, state staff experience levels, state legislation or administrative actions affecting state-run programs, and state occupational safety and health standards, we surveyed the 22 state-run programs that cover both private sector and state and local public sector workers, and obtained a 100 percent response rate.1

We conducted this survey via e-mail from May 2012 to June 2012. GAO staff designed the questionnaire in collaboration with a GAO survey specialist and a GAO attorney. To ensure the questions were relevant and clearly stated, we pretested the questionnaire with two officials from the Occupational Safety and Health State Plan Association, who also serve as administrators of the state-run programs in New Mexico and North Carolina. In addition, during a site visit to one state-run program (California), we discussed the survey questions and the state’s responses to ensure the questions were correctly interpreted.

Survey Question (1)

Which of the following sources of funds did your state use in federal fiscal year 2011 to meet the funding requirements to obtain a federal grant under section 23(g) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act?

| State | State general fund | Workers’ compensation fund | Other sources | Description of other sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | X | X | X | Small portion from general fund program receipts from asbestos certification fees |

| Arizonaa | X | |||

| Californiaa | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | |||

| Indiana | X | |||

| Iowa | X | |||

| Kentucky | X | |||

| Maryland | X | |||

| Michigana | X | X | Corporation fees and security fees | |

| Minnesota | X | |||

| Nevada | X | X | OSHA penalties and fees | |

| New Mexico | X | |||

| North Carolina | X | |||

| Oregon | X | |||

| Puerto Rico | X | |||

| South Carolina | X | X | Earmarked and restricted accounts within the agency | |

| Tennessee | X | |||

| Utah | X | |||

| Vermont | X | |||

| Virginiab | X | |||

| Washington | X | |||

| Wyoming | X |

Source: Responses to GAO's survey.

a Arizona, California, Michigan, and Tennessee specified a tax on workers’ compensation premiums as the state funding source.

b Virginia state-run program officials reported that they are in discussions with the Virginia Workers’ Compensation Commission on a proposal in which they would provide matching funds to the state for one full-time equivalent staff member as a pilot project to assist industries and employers identified by the commission.

Survey Question (2)

Approximately what percentage of safety and health inspectors, that were employed by your state occupational safety and health program as of December 31, 2011, had the following years of service?

| Safety inspectors | Health inspectors | |||||