An Employer's Guide to Skin Protection

-

Guide to Skin Protection

The following are links to all of the items in this collection:

Summary Statement

An in-depth discussion of skin protection, including recognition of skin problems, causes, the science behind them and methods to protect against them, focused on the employer. Part of a collection. Click on the 'collection' button to access the other items.

2000

This material is supported in part with funds from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) through CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training to a consortium of CPWR, the Operative Plasterers & Cement Masons International Association, and FOF Communications. Researched, developed, and produced by FOF Communications.

The material does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of NIOSH. Mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations does not imply endorsement by NIOSH, the U.S. Government, CPWR, OPCMIA, or FOF Communications.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 makes the employer responsible for providing a safe and healthful workplace that is free of recognized hazards.

© 1999, 2000 FOF Communications

Table of Contents

1.

Recognizing Skin Problems

2.

Worksite Exposures

3.

Neutralizing pH

4.

Modify Cement at the Plant?

5.

Best Practices at Home and Work

6.

Put Protection into Action

7. Evaluating Your Success

8.

Medical Approaches

Glossary

Best

Practices Checklist

Symptoms

Checklist

Selected

References

If your

employees work with wet cement products—concrete, mortar, plaster,

grout, stucco, or terrazzo, this handbook is for you. It will help you

prevent employee skin problems from cement.

Development of this handbook was supported by the National Institute for

Occupational Safety and Health/CPWR Consortium on Preventing Contact Dermatitis.

Consortium partners are CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training, the

Operative Plasterers & Cement Masons International Association, and

FOF Communications. The handbook was researched, developed, and produced

by FOF Communications.

The consortium steering committee includes: Boris Lushniak, MD, of NIOSH;

David Hinkamp, MD; Jon Mullarky and Greg Vickers , National Ready Mixed

Concrete Association; William Schell, Operative Plasterers & Cement

Masons International Association; John Sullivan, Jr., P.E., American Portland

Cement Alliance; Azita Mashayekhi, International Brotherhood of Teamsters,

and Eileen Betit, International Union of Bricklayers & Allied Craftsworkers.

The consortium has been instrumental in focusing the cement industry on

skin problems and in disseminating innovative protective measures such

as the use of neutralizing agents.

The consortium supported a Physician Alert brochure to help cement

products workers talk with their doctors; the Save Your Skin booklet

on glove wear; a Safety & Health Practitioner’s Guide;

a Tool Box Pamphlet; a worker classroom training program; a training

evaluation study; jobsite visits for pH testing of surface skin and rinse

water; a stakeholder symposium, and a professional advisory group meeting

on the development of this handbook. To learn more, visit NIOSH at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/skin/occderm-slides/ocderm.html

or CPWR at www.cpwr.com

or call the NIOSH Technical Information Branch (800-356-4674) or CPWR

(301-578-8500).

Recognizing Skin Problems

Ted Jason’s

eight-year old daughter got a painful rash that would not go away. The

Jasons took her to several doctors. They applied ointments. They washed

her sore skin with prescribed soaps. Nothing they did made a difference.

Then Ted took a course on preventing dermatitis from cement. He learned

to measure the pH of the surfaces of his boots and his car interior.

Ted found out that

alkaline cement dust from his work had contaminated his life in a way

he had never before appreciated. He realized his daughter had been exposed.

So Ted began following the tips given in the course. He cleaned his car interior and began removing his work clothes before getting into it. He switched to pH-neutral soap for his daughter. Within a few weeks, her skin problem was gone—and so was his.

WHY WORRY ABOUT

CEMENT?

Ted Jason’s

problems are not uncommon. Maybe you have a skin problem from cement or

know someone who does. Portland cement is estimated to account for 25%

or more of all work-related skin problems worldwide.

11

Reported lost work days for skin problems in US masonry trades are 2.5 times the national average. Concrete workers lose time at 7 times the average. Concrete workers report 4 times more lost work days for skin problems than do all construction workers. 24

Most experts agree that reported lost time is just the small tip of a very large iceberg of disease. So a statistically reliable survey 15 of apprentice cement masons was especially alarming. |

71% of apprentices hadone or more skin problems. Only 29% reported no skin problems. |

A surprising 71% of apprentices reported one or more skin problems. Only 29% reported no skin problems. The apprentices averaged only 3.3 years of experience in the trade.

|

Only 7% reported lost time or doctor visits for skin problems. |

Only 7% of those with skin problems reported lost time or doctor visits for their problems. 93% of the apprentices with skin problems continued to work without seeking medical treatment—setting themselves up for lifelong health problems.

Four types of

skin problems happen most often among cement products workers:

- Irritation

or dry skin (mild ICD)

- Irritant contact

dermatitis (ICD)

- Allergic contact

dermatitis (ACD)

- Caustic burns (cement burns or chemical burns)

There are different ways to get a long-lasting skin problem. There is no single pattern. You cannot predict who will get skin problems based on experience or on medical tests.

- Dry skin (mild ICD) may include scaling, itchiness, burning, redness. Dry skin may be called xerosis. An employee’s cement exposure can lead directly to dry skin or irritation.

- Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) can be acute or chronic. It can include stinging, pain, itching, blisters, dead skin, scabs, scaling, fissures, redness, swelling, bumps, and watery discharge. Sometimes irritation leads to infection. Cement exposure can lead directly to ICD or skin damage without first causing dry skin.

- Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an immune response. It is like other allergies but it involves the skin. ACD includes many symptoms of ICD. ACD is difficult to cure. The allergy may last a lifetime. Cement exposure can lead directly to ACD. This can happen without any warnings, such as local irritation.

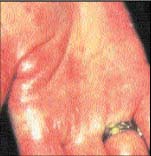

- Caustic burns (cement burns) are alkali burns. They should be referred to a medical specialist without delay. By the time an employee becomes aware of a burn, much damage has been done and further damage is difficult to stop. Cement burns look like other burns. They produce blisters, dead or hardened skin, or black or green skin. Cement burns also can lead to allergic dermatitis.

WHAT DO SKIN PROBLEMS

COST?

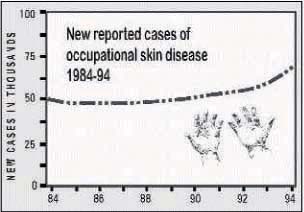

Each year occupationally-related skin problems affect one American worker

in a thousand. No one knows how many family members are affected by contaminants

brought home from the job. Skin problems are the second most common work-related

disorder in the US, surpassed only by ergonomic problems. Reported skin

diseases are about 15 to 20% of all work-related disease.

25

What

do occupational skin problems cost the US economy each year?

Estimated costs for medical care, lost production, and disability payments for reported skin disorders total up to $1 billion a year, according to NIOSH.

The costs to employers include worker compensation disability claims, lower productivity, and poor morale. The costs to workers include reduced earnings, medical bills, loss of a trade, social disability, embarrassment, and lower quality of life.

The rates of most other occupational injuries and disease have fallen. But skin disease rates have increased. Little progress is made, even though the causes are better understood and more methods of control exist now than ever before.

‘DERMATITIS WON’T KILL YOU’

A nameless industry leader said this not long ago before a training class on preventing contact dermatitis.

It may be true—although some workers with disfiguring cement burns or rampant chrome allergy dermatitis might wish it would.

Skin problems from cement are widespread and, unfortunately, they are too often tolerated as part of the price of work in some trades.

Our tolerance permits the high rates of occupational skin problems in the United States to continue.

But put yourself in the place of a worker with a persistent skin problem. If your hands or other skin are covered with rashes, irritation, or sores, it can make you less socially acceptable as well.

Many male cement products workers have said their wives or girlfriends do not appreciate their skin problems. Young single men and women with occupational skin problems often feel at a disadvantage when socializing. Whether the cement products worker goes to a school conference and shakes the teacher’s hand, goes to a bank and shakes the loan officer’s hand, or goes to a broker to make an investment—in every aspect of American life, an occupational skin problem can make the individual feel less than comfortable.

Social disadvantages do not take into account physical pain and suffering, the loss of morale, the loss of income, or the loss of personal leisure time devoted to grappling with an ongoing health problem.

As a conscientious employer, you have many motives for caring about your employees’ skin. Some of them are financial. Some of them involve productivity.

Some

of every employer’s motivation

should come from concern

for employee quality of life.

WHAT CAUSES SKIN PROBLEMS?

Skin

may be affected by one or more of the following factors:

- worksite materials,

- worksite conditions,

- environmental factors, and

- individual factors.

The skin is the single largest organ. It covers 20 square feet of surface. The skin's purpose is to protect the body from outside substances, chemicals, and bacteria.

Skin has two layers.

Together both are less than 1/8-inch thick.

- The epidermis (outer layer) is only 1/250th of an inch thick.

- The dermis is only 1/50th to 3/25ths of an inch thick.

The skin contains oil glands, hair follicles, and sweat glands—all are like tiny holes. So the skin can be like a leaky roof or a sponge when it contacts chemicals. Skin also contains blood vessels. Some chemicals can penetrate the skin and enter the bloodstream.

Normal surface skin

is moderately acidic. Recent research has shown that this ‘acid mantle’is

necessary to allow the skin to repair itself after an external ‘insult.’An

alkaline pH impedes repair.

Worksite materials can cause skin problems. Some materials ‘insult’ and injure skin. Some pass through it into the bloodstream.

-

Portland cement

is very alkaline (caustic) when wet so it affects skin surface

pH. Cement is hygroscopic so it draws moisture from skin.

Cement products

are abrasive and physically damage the skin surface, making it

a less effective barrier against chemicals. The moisture in eyes, mucous,

and sweaty or damp skin can activate dry cement, making it caustic.

These factors allow cement to cause dry skin and irritant contact dermatitis.

Sensitizers

in workplace materials may cause an allergic response. The reaction

may be local or widespread. Sensitization is an immune response. The

immune system fights a foreign substance. Usually, the material causes

no change on first contact. Once a person is sensitized, small amounts

can trigger a strong reaction. Many people cannot tolerate further exposure.

Possible sensitizers

used by cement products workers include: hexavalent chromium (Cr6+

) in cement, chemical admixtures in concrete, epoxies, additives in

rubber gloves, and other trace metals in cement products.

Hexavalent chromium

(Cr6+) is a sensitizer. It is an important cause of

allergic contact dermatitis. Cement’s alkalinity increases skin

absorption of this soluble chromate. Some studies show that Cr6+

penetrates the skin and enters the bloodstream.

Worksite cleaners too often are caustic and abrasive. They also may contain sensitizers like lanolin, limonene, or perfume and irritants like alcohol.

Worksite conditions

can determine whether a worksite material will cause skin problems.

- How long does

the material contact the skin?

- How often does

a worker use the material?

- Is there mechanical

trauma or abrasion of the skin (a break in the barrier)?

- Is the material

trapped or occluded to the skin with gloves, creams, lotions, petroleum

jelly, or barrier creams?

- Are there adequate hygiene facilities?

Environmental factors can cause skin problems directly or they can

work with other factors to increase skin problems:

- Heat causes sweating. Sweat dissolves chemicals and brings them into closer contact with the skin. Heat increases blood flow at the skin surface and increases absorption of materials into and through the skin.

- Cold dries the skin and causes microscopic cracks. Cold changes blood flow at the skin surface and leads to loss of feeling.

- Humidity increases sweating. High humidity keeps sweat from evaporating. Extremely low humidity can dry skin as sweat evaporates.

- Sun burns and damages skin. Sun can increase absorption of chemicals. Sun reacts with some chemicals to cause photosensitization.

Individual factors

can affect work-related skin problems. These include:

- pre-existing

dermatitis

- genetic predisposition

- knowledge

- attitude

- personal behavior/workpractices

Worksite Exposures

More than 92.7 million

metric tons of cement were consumed in US construction in one recent year, according to the Portland Cement Association . Cement consumption

has increased every year since 1991.

21

year, according to the Portland Cement Association . Cement consumption

has increased every year since 1991.

21

Cement is a mixture

of lime, silicates, aluminum, iron, magnesium, and other additives such

as gypsum, fly ash, and blast furnaceslag.

1

Cement is a component in:

- concrete—a

mixture of portland cement, water, fine and course aggregate, and chemical

admixtures,

- mortar—a

mixture of Portland cement and fine aggregate,

- plaster—a

mixture of lime, water, and sand, and may contain gypsum or Portland

cement as a binder (Slaked lime or calcium hydroxide is extremely caustic.),

- stucco—an

exterior finish material composed of Portland cement, lime, sand, and

water,

- terrazzo—an underlayer of Portland cement containing marble chips and tinted concrete,

- tile grout—a fluid mortar mixture consisting of Portland cement and water with or without aggregate, and

- other products.

Portland Cement

Products Workers

More than 1,300,000

American workers in 30 occupations are regularly exposed to wet cement.

The families of these workers may be exposed to cement dust on their work

clothes.

Following is a partial list of the construction trades workers who may be regularly exposed to cement:

- bricklayer,

- carpenter,

- cement mason

or concrete finisher,

- concrete truck

driver,

- construction

craft laborer,

- hod carrier,

- plasterer,

- terrazzo worker,

- tile setter,

and

- others.

Portland Cement

Work Tasks

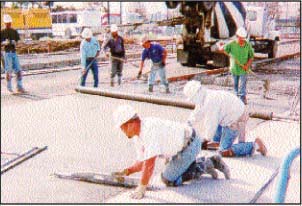

Below are some of the work tasks that expose construction workers to Portland cement:

tending concrete pour,

tending concrete pour,

- mixing and spreading

grout,

- preparing cement

underlayer for terrazzo,

- hosing out ready

mixed concrete truck, mixer, and chute,

- using mortar

to set brick, block, and other masonry,

- dismantling formwork

contaminated by Portland cement,

- pouring, leveling,

smoothing, and finishing concrete,

- attaching tiles

to walls, floors, and ceilings,

- mixing mortar

and providing it to other craftsworkers,

- mixing and applying

plaster, stucco, and EIFS, and

- spraying Portland cement products such as fireproofing, gunite, or shotcrete.

The Nature of

Cement

Cement has many properties which are damaging to skin. Cement is alkaline, or caustic. The pH of wet cement ranges from 12 to 13. Cement is hygroscopic, pulling moisture from the skin. Cement is abrasive. Cement may contain sensitizing chemicals and metals, such as hexavalent chromium (Cr6+).

The composition of cement varies somewhat from region to region. However, the alkaline, abrasive, and hygroscopic properties of cement in concrete, mortar, grout, plaster, stucco, and other products are universal.

Perhaps most frequently damaging of all these properties is the alkaline pH.

Normalizing pH

Wet cement is an alkali, or caustic. A caustic is any strongly alkaline material with a corrosive or irritating effect on living tissue. Alkalinity is essential in the development of irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) from cement. 4

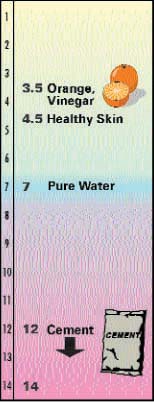

pH is a measure of

the alkalinity or acidity of a material. Pure water has a pH of 7 and

pH 7 is considered pH-neutral.

Strong alkalies are

pH 12 to 14. Cement is extremely alkaline, or caustic, with a pH value

of 12 to 13. Strong acids are pH 1 to 3.

pH represents the acidity or alkalinity of a watery solution on a scale. The pH scale is like the Richter scale for earthquakes. Both are logarithmic. On a logarithmic scale, the intervals between numbers are not equal. Rather, each number may be many times greater or smaller than the previous number.

|

pH 13 is one million times more alkaline than pure water at pH 7. pH 1 is one million times more acidic than pure water. What is the pH of an orange? An organe has a 3.5 pH level. |

|

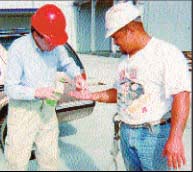

One of the authors tests surface skin pH of a cement products worker. Even though this worker and others wore gloves, their skin surfaces tested at pH 9 to 12, the same range as those workers who wore no gloves. |

|

Wearing gloves without good hygiene practices appears to be no more protective than no gloves at all.4 Neutralizing alkaline cement requires clean running water and pH-neutral or acidic soap.19 It may be helpful to use a buffering solution to normalize surface skin pH.9 |

pH Values

Like the earthquake

scale, the pH scale is logarithmic. So the intervals between numbers are

not equal.

Every whole number is a 10-fold change in alkalinity or acidity.

| An

orange is pH 3.5, like vinegar.

Healthy skin is 4.5. Acidic pH is <7 to <1. Pure water is pH 7. Alkaline or

caustic pH is >7 to 14. Cement is

up to 1,000,000,000 times more alkaline than human skin. |

|

Acids ionize in water to give H + (hydrogen) ions. Alkalies (bases) produce OH - (hydroxyl group) ions in water. You can learn more about the technical chemistry of pH by looking in a chemical dictionary or a chemistry textbook.

The pH Of Healthy Skin

Normal skin is pH 4.5 to 5.5, meaning it is moderately acidic. The acidic pH of skin has been recognized for a century. However, the purpose of the ‘acid mantle’ of skin is not completely understood. Scientists believe it has to do with processing of lipids (fats) required for skin barrier function. Contact with wet cement changes skin pH to alkaline. At alkaline pH, skin barrier repair is slowed, damage is prolonged, and skin problems are worsened.

The slightly acidic pH of normal skin also helps it to resist bacterial infection. Bacteria don’t like acidic environments. In fact, meat inspectors test pH as a measure of freshness. When the pH of meat becomes slightly alkaline, bacteria are more likely to multiply.

Further, alkalinity contributes greatly to skin absorption of the hexavalent chromium (Cr6+) in cement.3 So a cement worker’s absorption of Cr6+ can be greatly increased when it contacts skin in cement.

Acids

Acids are a large class of chemicals with pH values ranging from less

than 7 to less than 1. Acids with pH 1 are one million times more acidic

than pure water.

Examples of strong acids are hydrochloric acid (HCl), nitric acid (HNO3), and sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Strong acids burn skin immediately.

Strong alkalies can be more dangerous because they damage skin slowly without immediate pain. An alkali can remain on skin for hours before a burn is felt.

Weaker acids include vinegar and citric acid (oranges).

When an acid is added to an alkali, it tends to neutralize the pH. For example, if you add vinegar to cement water, it can reduce the pH from 12 to 8. You can do this experiment with small amounts of cement water and vinegar using the pH indicator papers pictured below. (The reaction of acids and alkalies together can release heat.)

Buffers

A buffer is a substance that can neutralize either an acid or an alkali. A buffer may be a mixture of a weak acid and a salt of that acid that is intended to maintain a desired pH. Phosphates are often used as buffering agents.

In addition to eliminating

the caustic effect of cement, neutralizing pH may convert hexavalent chromium

(Cr6+) to trivalent (Cr3+), reducing the risk of

ACD.

pH Indicators

pH indicator papers, like those below, make it easy to get reasonably

accurate measurement of pH on skin surfaces, car interior surfaces, and

other places. To test skin or dry surfaces, moisten the indicator in distilled

water. Then apply it to the test surface. To test a liquid, dip the indicator

in the liquid. Full range indicator papers (pH 1 to 14) work best for

cement.

A pH test meter, shown below, can be used to test rinse bucket pH. However,

cement particles in the water can clog this instrument. Paper test indicators

are probably more reliable for that reason.

pH-Neutral and Acidic Soaps

Caustics like wet cement can dry and irritate the skin. But did you know the soaps your employees use for cleanup at work and at home could make the problem worse? Many well-known soaps and cleaners are caustic. These soaps or cleaners can add to the dryness and irritation caused by the caustics used at work.

Your employees may be better off with a soap that is pH-neutral or slightly acidic. These soaps are closer to the pH of healthy skin. They also help “neutralize” the effect of worksite caustics.

For best results in selecting the right soap, the worker should consult a doctor.

To help select appropriate soaps, we tested the pH of some popular brands. We also checked the ingredients listed on the MSDSs.

The chart lists pH values for 39 soaps and cleaners.

pH-neutral and slightly acidic soaps and cleaners are good bets.

| Bar Soaps | pH Value |

| Basis | 9 |

| Caress | 7 |

| Clearly Natural | 9 |

| Coast | 9 |

| Dial | 10 |

| Dove | 6 |

| Grandma's Oatmeal | 10 |

| Irish Spring | 10 |

| Ivory | 10 |

| Jergens | 10 |

| Kiss My Face | 11 |

| Lava | 9 |

| Lever 2000 | 9 |

| Neutrogena | 9 |

| Oil of Olay | 7 |

| Palmolive | 10 |

| Safeguard | 9 |

| Shield | 9 |

| Tom's of Maine | 10 |

| Tone | 10 |

| Vermont Country | 9 |

| Yardley | 10 |

| Zest | 10 |

| Liquid Soaps | pH Value |

| Aloe Vera 40 | 6 |

| Cetaphil | 6 |

| Dial | 6 |

| Dove | 6 |

| Gillette Wash | 6 |

| Gojo Orange | 5 |

| Gojo Cream | 8 |

| Ivory | 6 |

| Jergens | 6 |

| Joy | 6 |

| Lever 2000 | 6 |

| Neutrogena Rainbath | 6 |

| Noxema | 7 |

| Palmolive | 7 |

| pHisoderm | 5 |

| Softsoap | 6 |

| In addition to these factors, consider possible allergies and other potential problems. Watch the skin’s reaction to a new soap. Read the label. Call the manufacturer and get an MSDS. Discuss all skin conditions with your physician. | |

| Don’t be fooled by advertising. Many soaps may promote themselves as ‘gentle,’ ‘natural,’ or ‘pure.’ But they are actually caustic. This may be fine for people who do not work daily with alkalies or caustics. But it may be irritating to the skin of workers who use cement. |  |

pH-neutral is 7. Soaps with pH below 7 are more acidic—like citrus or vinegar. Soaps above pH 7 are more caustic—like cement.

Regardless of pH, any soap containing lanolin, limonene, or perfume probably should be avoided if you are sensitive to those ingredients.

The chart is advisory only. To obtain reliable information, ask your pharmacist or ask the soap manufacturer for an MSDS. The authors do not endorse any products or claim the list to be accurate or complete.

Modify Cement at the Plant?

As industry leaders learn about skin problems, they often ask whether cement can be modified to reduce the hazards. Different modifications are proposed depending on the specific skin problem. Remember, cement causes two main problems: irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Cement causes ICD because it is alkaline, hygroscopic, and abrasive. Cement causes ACD because it contains sensitizers, mainly hexavalent chromium (Cr6+).

Neutralize pH?

Some in the industry have asked that manufacturers reduce the alkalinity of cement. By nature, wet cement is pH 12 to 13. It will always be alkaline. Attempts to neutralize the pH of cement would chemically alter it and possibly invalidate its specified integrity. Upholding the structural integrity of cement and concrete is paramount. Rather than attempt to neutralize the pH of an entire batch of cement at the plant, it seems more practical to neutralize the pH of the small amount of cement that may contact the surface skin of cement products workers at the jobsite. This can be done with a neutralizing solution.

Reduce Hexavalent Chromium?

When ferrous (iron) sulfate is combined with hexavalent chromium in cement, it forms an insoluble trivalent compound when water is added.

Trivalent chromium (Cr 3+ ) is not easily absorbed by skin. Finnish, Danish, and Swedish scientists have published studies showing that this way of modifying cement at the plant—as required by legislation in those countries—greatly reduced ACD in cement products workers. 20 ACD from cement is a common occupational dermatitis among construction workers and a reduction in the chromate content of cement would be a reasonable preventive measure. 2,3

American cement makers experimented with iron sulfate but could not duplicate the Scandinavian results for several reasons.

First, more than 120 plants make US cement and the product ships long distances in this country. If iron sulfate is added, the time it takes to transport the cement may result in spontaneous oxidation of the ferrous ion to the ferric form, rendering the iron sulfate inactive.

Second, the addition of iron sulfate during grinding is a patented process. Royalties and the cost of iron sulfate as an additive (variously estimated at $.05 to $1.00 per ton) would increase the cost of cement products. Added costs may be incurred in reconfiguring manufacturing processes to allow for the addition of iron sulfate.

As an alternative, some researchers have recommended that iron sulfate be added during mixing of concrete or when delivering premixed cement products to the worksite. 8,12

Finally, cement products may be modified in another way to reduce Cr6+ levels. Slag can be substituted for clinker at the plant. 11

American manufacturers express concern about possible effects of such methods on the structural integrity of finished concrete. For example, some argue that addition of substantial amounts of iron sulfate to concrete might cause durability problems or necessitate adjustment of the amount of gypsum added. (Concrete in Scandinavia and Singapore appears unaffected by modifications to cement in those countries.) Manufacturers point out that American specifications for concrete are rigid, that any changes must be well researched, and that research is ongoing. So change may be possible some day.

Best Protective Practices

Protecting skin is not simply a matter of wearing gloves. Alarge percentage of cement products workers already wear gloves. But, to be effective, glove wear must go hand-in-hand with proper hygiene. Hygienic practices and use of the correct gloves will prevent contact with cement. Glove wear without hygiene practices is no more protective than no gloves at all. 4 In fact, it can make problems worse.

This chapter presents

the best protective practices for preventing skin problems from

cement.

- Best practices

at home.

- Best practices

at work.

- Best practices

in emergencies.

- The Best Practices Checklist.

Not everyone can

do all these practices. But your employees should do as many as possible,

beginning with the easiest ones. There is no guarantee that any or all

of these practices will prevent skin problems from cement. But these practices

are recommended by experts and they represent the best protections known.

What are your company’s best practices for preventing dermatitis? Before you read this chapter, take a few minutes to list them on a separate piece of paper.

BEST PROTECTIVE

PRACTICES AT HOME

Tell Employees About pH-Neutral Soaps

Recommend to your

employees that they wash with pH-neutral or acidic soaps. A pharmacy can identify one.

can identify one.

Remember the discussion

about neutralizing caustics?

Cement products workers

who wash with alkaline soaps unknowingly continue to ‘insult’

their skin with alkalies. During the day they are exposed to caustic cement.

At home they are exposed to caustic soap.

If cement products

workers wash with pH-neutral or acidic soaps at home, it may help restore

the desired pH balance of the skin surface. This allows skin barrier repair

to proceed. If skin remains at an alkaline pH, skin barrier repair is

impeded.

Recommend Separate Laundering Of Work Clothes

Employees should change out of work clothes at work. Work clothes can be brought home in a separate container. A trash bag works great. This practice keeps cement out of the car or truck interior.

Launder work clothes

separately to protect family or roommates. For extra safety, run washer

empty after laundering work clothes.

(Remember Ted Jason’s daughter?)

|

Dry Skin or Irritation (Mild ICD). When cement becomes wet, liberated calcium hydroxide increases the pH in the alkaline direction. Wet cement has a pH value 12 to 13. This is one billion times more alkaline than skin. The result may be dry skin or mild irritant contact dermatitis. |

| Irritant Contact Dermatitis. Alkalinity is essential in the development of irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) from cement. At alkaline pH, human skin is more permeable to many hazards. As the skin's barrier layer becomes more permeable, repeated contact with abrasive materials also may contribute to ICD. |  |

|

Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Most cement contains metals or other chemicals which are sensitizers, or allergens. Foremost among them is hexavalent chromium (Cr6+). Others may be present in admixtures: accelerators, water reducers, superplasticizers, retardants, air entraining agents, or polymer-modified systems. |

| ‘Cement burns.' The occurrence of alkali burns from cement is well documented. No official data exist on the annual number of cases. A statistically valid survey 15 found cement burns among 35% of apprentice cement masons. In severe cases, these burns can cause scarring, even disability. |  |

|

ICD due to alkaline soap. Alkaline soaps can cause dermatitis even in the absence of other exposures. Alkaline soaps can worsen skin problems caused by cement and are not recommended for cement products workers.

|

| Allergic Dermatitis Due to Lanolin. Some individuals may develop a sensitivity to lanolin. Cement products workers should avoid lanolin-containing products at the worksite because lanolin can occlude cement residue to the skin. Lanolin-containing products should be applied only to clean, dry skin in a clean environment. |  |

BEST PROTECTIVE

PRACTICES AT WORK

Each Employee

Needs At Least 5 To 7 Gallons of Clean Running Water Per Day

Bring clean running

water to the jobsite. Employees need clean water for washing before work,

whenever they break, and at the end of the shift. Prohibit cleaning with

abrasive solvent  containing

products. These include waterless hand cleaners like the alcohol-based

gels or citrus cleaners. Such cleaners are not suitable for cement

exposure.

containing

products. These include waterless hand cleaners like the alcohol-based

gels or citrus cleaners. Such cleaners are not suitable for cement

exposure.

Consider providing buffering spray to reduce the pH of any cement residue

on the skin.

Require Employees

To Wash Hands Before Putting On Gloves

Employees should

wash with pH-neutral soap and clean running water, as recommended by the Portland Cement Association’s sample MSDS.

Portland Cement Association’s sample MSDS.

Dry Hands

Workers should dry hands thoroughly with a clean cloth or paper towel before putting on gloves.

Wash Hands Again

If Gloves Are Removed

If employees remove

gloves during work,  they

must wash again with clean water and pH-neutral or acidic soap. If not,

cement residue will enter the gloves. Don’t allow employees to rinse

their hands in tool rinse buckets.

they

must wash again with clean water and pH-neutral or acidic soap. If not,

cement residue will enter the gloves. Don’t allow employees to rinse

their hands in tool rinse buckets.

Long Sleeves Buttoned

Or Taped Inside Gloves

Many experts recommend

wearing long sleeves and taping them inside gauntlet gloves. But if the

sleeves become saturated with wet cement, they must be removed immediately.

Rubber Boots With

Pants Taped Inside

Rubber boots

prevent contact with cement. When pants are taped inside, cement will

not enter the boots. Wet cement inside boots is a common event leading

to severe and possibly disabling cement burns. Cement masons or concrete

finishers should use kneepads and knee boards if they kneel on wet concrete.

Rubber boots

prevent contact with cement. When pants are taped inside, cement will

not enter the boots. Wet cement inside boots is a common event leading

to severe and possibly disabling cement burns. Cement masons or concrete

finishers should use kneepads and knee boards if they kneel on wet concrete.

Never Let Cement

Remain On Skin Or Clothes

When wet cement gets on permeable clothing, it must be removed immediately. When wet cement gets on skin, it must be washed with clean water and pH-neutral or acidic soap. At the least, consider providing a buffering solution to neutralize the pH of cement residue.

Provide Or Require

Proper Gloves

Prohibit Barrier

Creams

Barrier creams or

‘invisible gloves’ are not recommended for cement work.

19

The abrasive cement probably breaks the seal of the barrier cream. Also,

reapplying the cream in the work area may occlude or seal cement to the

skin.

Provide Glove

Liners

Glove liners of thin cotton help make gloves more comfortable. They can help keep hands clean and dry. But they must not be contaminated with cement inside the gloves. The goal is to keep the insides of the gloves clean.

Throw Out Grossly Contaminated Gloves

Gloves should be cleaned every day before and after removal. Sometimes gloves get so contaminated they cannot be cleaned. Throw them out.

Require Employees

To Clean Gloves Daily

Clean reusable gloves daily. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

Place clean gloves in a baggie.

Store gloves away from tools and materials in a cool, dark, dry place

Consider Providing

Disposable Gloves

Disposable gloves

can make it easier for employees to keep their hands clean. Disposable

gloves can be less expensive than reusable gloves.

The only

drawback to disposable gloves is that workers sometimes wear them day

after day.

The only

drawback to disposable gloves is that workers sometimes wear them day

after day.

To remove disposable gloves, peel back from the top, turning them inside

out.

Discard disposable gloves at the jobsite each day.

Teach Employees

How To Remove Gloves

|

Before removing

gloves, always clean off the outsides. Follow the manufacture's instructions. Watch for pinholes which can let in contaminated rinse water. |

|

To remove gloves, loosen them on both hands. Hold hands down so contaminated water will not drip onto skin or clothing. |

|

|

Remove

the first glove only to the fingers.

The cuff of the glove will remain over the palm. |

|

Now, grabbing

the second glove with the first glove, remove the second glove. The first glove should slip off. |

|

|

Try to handle gloves by the insides only. Don’t touch the outsides. |

No Jewelry at

Work

|

Cement

can collect under rings, watches, or necklaces. Wet cement trapped

against skin for long periods is hazardous. |

Encourage Employees

To Change Work Clothes At Work

Removing work clothes at work cuts cement exposure for employees and their family members. It keeps cement out of the car or truck interior. If work clothes cannot be left at the job, they should be taken home in a separate container. A trash bag works great.

| Instruct

Employees to Avoid Lanolin, Petroleum Jelly, and Other Skin Softening

Products at Work |

|

Skin-softening products

can occlude or seal cement to skin, can increase the skin’s

ability to absorb contaminants, or can irritate the skin.

Never use petroleum jelly or other emollients to treat cement burns. Applying such products can intensify burns by trapping the cement against the skin.

Skin-softening products

should be applied only to clean skin in clean environments. A cement products

worker may use these products, if desired, at home after showering or

bathing with pH-neutral or slightly acidic soap.

But be careful. Some skin-softening products may contain fragrances, lanolin, or other chemicals that can cause ACD in susceptible workers.

Urge Employees

To See A Physician

Any employee with

a persistent skin problem, even a minor one, should see a doctor. A statistically

valid survey of apprentice cement masons showed only 7% of those with

skin problems saw doctors even though 71% had had problems in the last

year.15 Some did not think the problems were serious. Others were afraid

of losing employment.

To get effective

treatment, the cement products worker must inform the doctor about products

used at work. The goal is to provide medical treatment for a health problem.

To get effective

treatment, the cement products worker must inform the doctor about products

used at work. The goal is to provide medical treatment for a health problem.

The question of covering the treatment under worker compensation or a health & welfare plan is not a topic of this handbook.

A Physician Alert

brochure is available from CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training

(301-578-8500). The brochure can be given by a worker to a doctor. The

brochure helps explain the skin hazards of cement work.

Ideally, employers and unions can work together to find a way for employees

to see doctors about skin problems before they become chronic and untreatable.

The “Physician Alert” tips can help employees and physicians

talk. So can a product Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS).

Encourage employees

to follow the doctor’s prescriptions and recommendations. That action,

combined with other best practices, can lead to the successful control

of most cement-related skin problems.

Follow A Model

MSDS

Find the best Material

Safety Data Sheet in the industry and follow its recommendations. The

best MSDS is the one that is most complete and provides the most protective

recommendations.

The Portland Cement

Association (PCA) has published a sample MSDS report.19 It

includes a few of the best practices recommended by experts.

Remember, this MSDS is only the minimum guideline. With a little creative

thought and not too much effort, you can do a lot more for your employees.

Dusty clothing

or clothing wet with cement fluids should be removed promptly and laundered

separately before reuse.

Dusty clothing

or clothing wet with cement fluids should be removed promptly and laundered

separately before reuse.Employees must wash wet cement from the skin with clean water and pH-neutral or slightly acidic soap.

Employees cannot rely on pain or discomfort to alert them to a hazardous skin exposure.

Cement Burns

An acid will burn

skin immediately. Cement is sneakier. An employee can work with wet cement

on the skin for hours without feeling any discomfort. But the alkaline

burn of the cement is damaging the skin microscopically. That damage may

be just a cement burn or it also may be the cumulative injury that leads

to irritant or allergic dermatitis.

Cement burns (caustic

burns) are alkali burns. Cement burns progress. This means they get worse

even without more exposure. Anyone who feels a cement burn starting should

go immediately for emergency treatment in an ER or by a burn specialist.

Don’t assume the burn will not get worse. By the time an employee

becomes aware of a burn, much damage has already been done and further

damage is difficult to stop.

Medical experts recommend flushing the skin with lots of clean water. Some suggest adding vinegar, citrus, or a buffer to the water to help neutralize the caustic effect. 6,9,14,23

Put Protection into Action

Your workers deserve

training and protective gear. As an employer, you expect workers to follow

through by using to the fullest the training and protective gear you provide.

The construction industry has made many strides in protecting its workers from many safety hazards. Almost everyone agrees it must do more to protect workers from skin problems. But how can you achieve more protection for your employees?

As an employer, you’ve

shown your interest in progress by looking at this handbook. What more

can you do to protect your workers and to help them protect themselves?

This chapter presents some additional pointers and resources you can use to help put your concerns into action.

Choosing And Wearing

Gloves

The main goals for

successful glove wear are:

- keep materials

from penetrating or saturating gloves

- keep glove insides

clean and dry

To meet these goals,

you must make sure that:

- gloves fit

- gloves are cleaned

daily

- gloves are discarded

when worn out or grossly contaminated

- gloves are correct

for the worksite materials

Three types of gloves

are often used for work with wet cement:

- impermeable rubber

or butyl

- cotton or other

fabric

- leather

Some

gloves combine rubber or butyl with cotton, other fabrics, or leather.

Glove thickness and the length of the cuffs vary by task or worker preference.

Fabric or leather gloves are not recommended because they may become saturated

with wet cement.

Some

gloves combine rubber or butyl with cotton, other fabrics, or leather.

Glove thickness and the length of the cuffs vary by task or worker preference.

Fabric or leather gloves are not recommended because they may become saturated

with wet cement.

Without good hygiene, gloves are no better than no protection at all. If employees can’t wash with clean water and pH-neutral soap whenever they remove their gloves, the insides become contaminated. Don’t fool yourself. Gloves on employees are no proof of protection. 4

Below are the websites of two well-known glove manufacturers. You can purchase from these and others through your local safety supply store listed in the business section of the telephone directory.

http://www.bestglove.com

http://www.ansell-edmont.com

Training Video

|

A video for worker training “Skin Safety with Cement and Concrete” is available for sale from the Portland Cement Association. The video presents good safety tips and is reasonably candid about the hazard. It focuses more on cement burns than on preventing dermatitis. Portland |

Video Sales: 1-800-868-6733 |

Sample Material

Safety Data Sheet

The Portland Cement Association has published a sample material safety

data sheet for cement.

19

Among other recommendations is washing at the jobsite with running water

and pH-neutral soap.

http://www.cement.org

|

The “Cement Burn Awareness Kit” is available from the National Ready Mixed Concrete Association. The kit contains

color photographs, warning tools, and a sample MSDS to help prevent

cement exposure. |

Commercial products are marketed for neutralizing the pH of cement. Mason’s Hand Rinse is an acidic rinse. Neutralite is a buffering solution. In theory, either product or other similar products could be helpful if they neutralize cement on the skin surface.

|

Mason's

Hand Rinsetm

|

Neutralite

Solutiontm

|

| Libby Laboratories,

Inc. 1700 Sixth Street Berkeley, CA 94710 510-527-5400 FAX 527-8687 |

Force Field

Technologies P.O. Box 5381 Granbury, TX 76049 800-850-3908 FAX 817-326-5304 |

pH indicator papers

(pH test strips) can be ordered through your local safety supply company

or from Markson LabSales, Inc., at 1-800-528-5114 or Lab Safety Supply

at 1-800-356-0783.

Evaluating Your Success

Let’s say your

company wants to invest time and effort in improving conditions with the

aim of preventing skin problems from cement.

How will you know

if your efforts pay off?

You might say it’s

easy. I’ll see it with my own eyes. It will be plain to everyone.

But that’s probably not true.

Whether your company

employs five cement workers or 500, you can set up a system for measuring

the success of your prevention efforts. This chapter gives some simple

ideas about how to do it.

Compared To What?

When you evaluate

anything, you need a basis for comparison. Two classic methods

are ‘criteria-based’ and ‘norm-based’

comparison.

In school, did your

teacher grade your test by an objective standard and give ‘As’

only for 100%, for example? That’s ‘criteria-based’ evaluation.

Criteria-based means comparing something to an objective standard that’s

set up ahead of time.

If your teacher “graded

on a curve” by comparing you with other students in your class, that’s

‘norm-based’ evaluation. Norm-based means comparing something

with other things in the same category.

To measure your success in reducing skin problems from cement, first choose

your own basis for comparison. Do you want to compare your results with

an objective standard of 100% healthy skin and perfect protective practices?

Or should you measure progress by comparing results with existing conditions?

Measuring Tools

Whichever comparison method you choose, here are some tools you can use

to measure your results. You might also think of other tools.

- Observations

and reports of work/personal practices

- Symptoms checklist

- pH tests of surface skin

Norm-Based Evaluation

Consider comparing

your workers with themselves before and after beginning your efforts.

Before starting your

efforts, take some baseline measurements. Use written checklists.

Watch your employees work and take reports from them of what they do.

You don’t have to record the employees’ names. You are not comparing

individuals. You are comparing your employees as a group

before and after your efforts.

Which best practices are your employees currently doing? Which are they failing to do? Keep a written record of your observations. Have your employees complete the symptoms checklist of the skin problems they currently have. Assure them their names are not recorded and their answers have no effect on employment. Ask them to do a pH test of surface skin. Again, this is not a test of the individual employee. Instead, it is a measure of the success of the protective practices you implement.

Once you have a baseline

record, then begin your effort to reduce skin problems. Instruct employees

in best practices and beegin enforcing these practices on the job.

When you think your efforts may be starting to pay off, go around and

take your measurements again. Now count up the results and compare the

‘BEFORE’ and the ‘AFTER.’ If you or

someone in your company knows how to use a statistical computer program,

you can use it to help your evaluation. Or you can count by hand calculator

and see where there is progress. Keep a record of the outcome.

Take the same measurements periodically to assess progress. The results can help you adjust your efforts.

What If Employees

Are Transient?

In construction,

workers come and go. Turnover varies from company to company. Some larger

companies have a steady cadre of core workers and hire or layoff more

as projects demand. Other companies have no steady workers, only transient

ones. This makes evaluation more difficult. But not impossible.

Always keep in mind

that you are not evaluating individual workers. You are evaluating the

success of your efforts by looking at your employees as a group.

If all your workers are transient and other employers have poor hygiene conditions, you may not see immediate improvements in the symptoms checklist. But you should see improvements in the pH tests of surface skin and in compliance with best protective practices. This should help prevent future dermatitis.

Work With Others

If you work with

other employers and with employees’ unions, you can bring about a

reduction in skin problems in your labor pool.

Working together

and involving your health & welfare plan, you can implement a plan-wide

evaluation. It can look at the reduction in medical costs and worker compensation

disability settlements.

One expert recommendation is to identify one or more health care providers

who are willing to educate themselves about cement dermatitis. Taking

advantage of their expertise can make your efforts more effective.

It is vital that employees believe physicians have their health foremost

in mind. Workers must feel free to seek treatment without fear of impacting

future employment.

One attribute of

a good health care provider is a willingness to learn about a new group

of patients. As you begin working with health care providers who will

focus on treating and preventing skin problems among your employees, you

will want to give them appropriate background information. This will be

true whether they are dermatologists, occupational medicine physicians,

or other specialists.

The Physician Alert Brochure is available from CPWR (301-578-8500)

for this purpose. This handbook, including this chapter, also includes

information that may be helpful.

Health care providers

should be aware that cement products workers are exposed to materials

that cause dry skin, irritation, irritant dermatitis, allergic dermatitis,

and alkali burns.

Occupational skin disorders may develop not only at the hands but at any of several body sites including arms, neck, ankles, feet, and other locations. 1

Portland cement is alkaline (pH 13). Alkalinity is associated with development of ICD and ACD.4 Further, the human skin is more permeable at alkaline pH.

Cement contains trace amounts of hexavalent chromium (Cr 6+ ), a sensitizing agent responsible for allergic dermatitis (ACD) i cement products workers worldwide. Other sensitizing agents include epoxy adhesives, sealants, and admixtures in cement.

Some cement products workers use lanolin creams or petroleum-based emollients to soften their skin. If these products are applied to skin that is not thoroughly clean, they can intensify exposure.

Other skin disorders among cement workers include disorders caused by mechanical trauma; disorders caused by solar radiation, climate, or temperature, and contact urticaria (hives).

Development of skin

disorders from cement cannot be predicted based on experience. Exposure

may cause irritation or dry skin, ICD, ACD, or burns.

- Irritation or dry skin may include scaling, itchiness, burning, redness. It may be called xerosis. An employee can move directly from exposure to irritation or dry skin.

- Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) can be acute or chronic. It can include stinging, pain, itching, blisters, dead skin, scabs, scaling, fissures, redness, swelling, bumps, and dry or watery discharge. Sometimes irritation leads to infection which leads to ICD. An employee can move straight from exposure to ICD.

- Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) includes many symptoms of ICD. ACD is difficult to cure. It requires continued care and may require change in work. Reintroduction to exposure poses serious problems. An employee can move straight from exposure to ACD. This can happen without any warnings, such as local irritation.

- Cement burns are alkali burns. They can progress and should be referred to the ER or a burn specialist without delay. By the time an employee becomes aware of a burn, much damage has already been done and further damage is difficult to arrest.

PHYSICIAN ALERT

The next three sections

present etiologic agents, surveillance, and intervention/treatment options

which may be helpful to a physician evaluating the skin of a cement products

worker.

Etiologic Agents

Xerosis (dry skin).

Alkalies; abrasive cleaners; solvents; alkaline soaps; water; sun; heat;

cold; low humidity.

|

ICD. Portland

cement; plaster; lime; epoxies; solvents; abrasive cleaners; alkaline

soaps; hand/barrier creams; skin care products.

ACD. Portland cement; hexavalent chromium (Cr6+); trace metals in cement or concrete; plaster; stucco; mortar; grout; lime; epoxy resins, hardeners, reactive diluents; some admixtures; lanolin; rubber; perfumes. Cobalt sensitivity is reported from cements in Europe but not from American cement. 1

Burns. Portland

cement; lime; other alkalies; epoxy components.

Trauma. Friction; pressure; pounding.

The Elements.

Sun; heat; cold; sweat; low or high humidity.

Contact Urticaria

(Hives). Latex; rubber; epoxy resins; leather; clothing; cold; heat;

sun; water.

Workers exposed to cement include concrete masons, bricklayers, hod carriers, laborers, plasterers, drywall finishers, terrazzo masons, tile setters, sidewalk pavers, construction laborers, carpenters, ready mixed concrete truck drivers, and many others.

Surveillance

Dry Skin (xerosis,

mild ICD). Scaling; itchiness; burning; redness.

ICD. Exam;

stinging; burning; pain; itching; blisters; dead skin; scabs; scaling;

fissures; redness; swelling; bumps, dry or with watery discharge. Diagnostic

aids: open application tests; do not patch test to known irritants;

do not patch test to unknown chemicals.

ACD. Exam;

stinging; burning; pain; itching; blisters; dead skin; scabs; scaling;

fissures; redness; swelling; bumps, dry or with watery discharge; usually

concentrated where exposure occurs, but also occurs on other body parts;

onset 2 to 7 days or more after exposure. Diagnostic aids: open

application tests; commercially available skin patch tests (e.g., to some

rubber, epoxy, and cement compounds); do not patch test to known irritants;

do not patch test to unknown chemicals.

Burns. Blisters,

dead or hardened skin, black or green skin.

Trauma. Redness;

blisters; abrasions; thickening; discoloration; fissures; corns/callosities,

hives.

The Elements.

Burns; dry skin; scaling; itchiness; burning; blisters; sweat pore blockage

(miliaria); maceration; frostbite; immersion foot; discoloration; waxy

skin; redness; swelling; tenderness; numbness; hives; gangrene.

Contact Urticaria (Hives). Exam; hives; swelling; redness; itchiness; pain.

Intervention/Treatment

Xerosis (dry skin).

Exam and treatment: skin lubrication; change work practices; protective

clothing; gloves; mild soaps; temperature/humidity control.

ICD. Exam;

prevent exposure; proper gloves; long sleeves; remove work clothes if

soaked with wet cement; skin lubrication, antibiotics for infections;

astringent soaks; topical or systemic corticosteroids; antihistamines;

UV; wash hands at least before eating or leaving work with pH-neutral

soap; possibly add vinegar or buffering agent to neutralize alkaline wash/rinse

water.

ACD. Exam;

identify offending agent and prevent exposure; may require change in work

as reintroduction to exposure poses serious problems; proper gloves; long

sleeves inside gloves; remove work clothes if soaked with wet cement;

skin lubrication; antibiotics for infections; astringent soaks; topical

or systemic corticosteroids; antihistamines; UV; wash hands with pH-neutral

soap at least before eating or leaving work.

Cement Burns.

Flush with copious amounts of water; buffered solution to neutralize alkalies;

burn wound care; surgery; skin grafting; physical therapy. Cement burns

are alkali burns. They can progress and should be referred to a specialist

without delay.

Trauma. Exam

and specific treatment; change work practices; use of proper tools and

protective clothing.

The Elements.

Exam and specific treatment; sunscreens; change work practices; protective

clothing; temperature/humidity control.

Contact Urticaria (Hives). Identify and avoid offending agent; skin exam and treatment; antihistamines; systemic corticosteroids.

Visiting the worker’s worksite or reviewing the Material Safety Data Sheets of products used there may help to determine what substances the worker is exposed to, the degree and duration of the exposure, the methods and agents used to clean the skin, and the type of protective clothing used.

Outlook

Irritant Contact

Dermatitis (ICD). The prognosis of occupational irritant contact

dermatitis is poor.

7

Prevention is imperative. One study showed that 75% of patients with occupational

contact dermatitis developed chronic skin disease.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD). Chrome allergy is persistent. Trace amounts of chrome (Cr) are found in many articles of daily life, including food, water, and cigarettes. Cr may persist in tissues for a long time. A change of work does not always assure healing of the dermatitis and workers with mild to moderate dermatitis may be encouraged to remain at work. There is some evidence that the skin has the ability to reduce Cr6+ to Cr3+ enzymatically. 1,12 It also may be that neutralizing the pH of cement at the skin surface may convert Cr6+ to Cr3+ . (See reduction of Cr6+ in Scandinavian cement.) For some years, iron sulfate has been added to cement manufactured in Scandinavia. In one in vivo study, cements with and without iron sulfate were compared concerning their capacity to elicit allergic patch-test reactions in eight chromate-hypersensitive individuals. No patch-test reactions were obtained from a water extract of cement with iron sulfate when appropriately buffered. 5

Cement Burn. Following is a typical case history. A young male construction worker accidentally poured cement over the top of his boots. He was careful to rinse off all the cement from his boots immediately as advised. Three hours later, he experienced excruciating pain over the dorsum of his toes and on removing his boots and wet socks, discovered to his horror that the dorsum of all his toes had turned a ‘deadly green.' Clinically, he had full skin thickness burns of the dorsum of all his toes over the proximal phalanx which subsequently became infected and required hospitalization and daily dressing for three weeks. 6,9,14,23

The damage from cement burns may be worsened when a worker applies an emollient such as petroleum jelly in an attempt to soothe the pain. The emollient occludes the cement to the skin which increases the burn.

acids

A large class of chemicals with pH values ranging from <7 to <1. Acids with pH 1 are one million times stronger than acids with pH 6.

admixture

Any substance—other than cement, aggregate, or water—that is mixed with concrete; usually a chemical solution added to enhance a specific property of the concrete.

alkali

(al-kah-lie) Any substance which is bitter, irritating, or caustic to the skin, and has a pH value greater than 7. Strong alkalies are corrosive to skin and mucous membranes. Portland cement's ingredients make it extremely alkaline.

buffer

A substance that

can neutralize either an acid or an alkali. A buffer is often a weak acid

and so it releases less heat than a strong acid would when neutralizing

an alkali.

caustic

Any strongly alkaline material which has a corrosive or irritating effect on living tissue.

hexavalent chromium (Cr6+)

Chromium (Cr) is a metallic element with three valences: 2, 3, and 6. Elemental and trivalent (Cr3+) chromium are relatively non-toxic. But hexavalent (Cr6+) compounds are irritating and corrosive. Cr6+ is more readily absorbed by skin than is Cr3+. Cr6+ is a sensitizing agent. Trace amounts of Cr6+ are in most American cements as a production contaminant.

hygroscopic

(hi-jrah-skop-ik) Having a strong tendency to absorb water, which results in swelling. Cement is hygroscopic. It absorbs moisture from skin, drying it.

logarithmic scale

On a logarithmic scale, the intervals between numbers are not equal or linear. Instead, each number represents a value that is many times greater or smaller than the previous number. The pH scale and the Richter scale for earthquakes are logarithmic.

neutralize

To make chemically neutral or balanced. An alkali can be neutralized by adding an acid, and vice versa. Also see: buffer.

occlude/occlusion

(a-klood/a-kloo-zhun) To seal a material in contact with the skin surface. To take in and retain a substance on the interior rather than the exterior surface.

pH

pH is a value representing

the acidity or alkalinity of a watery solution on a logarithmic scale.

Pure water is the standard used in arriving at this value. Pure water

is pH 7. pH 1 is extremely acidic. pH 13 is extremely alkaline. pH 13

is one million times more alkaline than pure water. pH 1 is one million

times more acidic than pure water.

sensitizer

A material which

can produce a pathological immune response. An allergen. Hexavalent chromium

(Cr 6+ ) is a sensitizer or sensitizing agent. Once sensitized, further

contact must be avoided.

xerosis

Dry, scaling, itching

skin.

| BEST PROTECTIVE PRACTICES AT HOME |

| ___ 1. Use pH-neutral soap at home |

| ___ 2. Launder work clothes separately |

| BEST PROTECTIVE PRACTICES AT WORK |

| ___ 1. Wash with clean running water and pH-neutral soap. |

| ___ 2. Wear correct gloves. |

| ___ 3. Wash before putting on gloves. |

| ___ 4. Wash again whenever gloves are removed. |

| ___ 5. Use disposable gloves or clean reusable gloves daily. |

| ___ 6. Remove gloves properly. |

| ___ 7. Wear glove liners. |

| ___ 8. No jewelry at work. |

| ___ 9. Long sleeves buttoned or taped inside gloves. |

| ___ 10. Rubber boots with pants taped inside for concrete work. |

| ___ 11. Never let cement remain on skin or clothes. |

| ___ 12. Avoid barrier creams |

| ___ 13. Avoid skin softening products at work. |

| ___ 14. Change out of work clothes before leaving jobsite. |

| ___ 15. See a doctor for any persistent skin problem. |

| ___ 1. | Check if you had at least one skin problem during the last 12 months | |||||||||||||

| ___ 2. | Check if you currently have the skin problem. | |||||||||||||

| ___ 3. | If you have a skin problem, check all the words that apply | |||||||||||||

|

SURFACE SKIN pH TESTING

| Palm | pH ___ | Palm | pH ___ |

| Between Fingers | pH ___ | Between Fingers | pH ___ |

| Back of Hand | pH ___ | Back of Hand | pH ___ |

| Date | ______ | Date | _____ |

1. Adams, RM, Occupational

Skin Disease, Grune & Stratton, New York, 1983.

2. Avnstorp, C, Follow-up

of workers from the prefabricated concrete industry after the addition

of ferrous sulphate to Danish cement, Contact Dermatitis, 20(5):365-71,

May 1989.

3. Avnstorp, C, Prevalence

of cement eczema in Denmark before and since addition of ferrous sulfate

to Danish cement, Acta Derm Venereol, 69(2):151-5, 1989.

4. Avnstorp, C, Risk

factors for cement eczema, Contact Dermatitis, 25:81-88, 1991.

5. Bruze, M, et al.,

Patch testing with cement containing iron sulfate, Dermatol Clin,

Vol 8, No 1:173-6, January 1990.

6. Buckley, DB, Skin

burns due to wet cement, Contact Dermatitis, 8:407-409, 1982.

7. Cooley, J and

JR Nethercott, Prognosis of occupational skin disease, Occupational

Medicine: State of the Art Reviews, Vol 9, No 1:19-25, January-March

1994.

8. Cronin, E, Contact

Dermatitis, Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingston, 1980.

9. Feldberg, L, et

al., Cement burns and their treatment, Burns, 18, (1) 51-53, 1992.

10. Fregert, S, et

al., Reduction of chromate in cement by iron sulfate, Contact Dermatitis,

5:39-42, 1979.

11. Goh, CL and SL Gan, Change in cement manufacturing process, a cause for decline in chromate allergy? Contact Dermatitis, Vol 34, No 1:51-54, January 1996.

12. Halbert, AR,

et al., Prognosis of occupational chromate dermatitis, Contact Dermatitis,

27: 214-219, 1992.

13. International

Labour Organization, Geneva.

14. Koo, CC, et al.,

Letter to the Editor, Regional Burns Unit, Mount Vernon Hospital, Burns,

18, (6) 513-514, 1992.

15. Larson, M, and

Wolford, R, Survey of Apprentice Cement Masons, FOF Communications,

1997. (442 apprentices were surveyed using a questionnaire designed in

consultation with BD Lushniak, MD. Response rate was 100%. Mean years

in trade: 3.3; mean age: 27; most frequent age: 20.)

16. Lushniak, BD,

Epidemiology of occupational contact dermatitis. Dermatologic Clinics,

Vol 13, No. 3:671-680, July 1995.

17. Lushniak, BD,

The public health Impact of irritant contact dermatitis, Immunology

and Allergy Clinics of North America, Vol 17, No. 3:345-358, August

1997.

18. OSHA, Interpretation

of Standard 1926.51(f), RF Gurnham, Director, Office of Construction and

Maritime Compliance Assistance, February 2, 1994.

19. Portland Cement

Association, Report of Sample Material Safety Data Sheet for Portland

Cement, Skokie, IL, 1997.

20. Roto, P, et al.,

Addition of ferrous sulfate to cement and risk of chromium dermatitis

among construction workers, Contact Dermatitis, 34(1):43-50, January

1996.

21. Toal, W, chief

economist, Portland Cement Association, Skokie, IL, personal communication

with K Sweney of FOF Communications, June 1998.

22. van der Valk

PGM. and Maibach, H, The Irritant Contact Dermatitis Syndrome,

CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1996.

23. Vickers, HR,

and Edward, DH, Cement burns, Contact Dermatitis, 2:73-78, 1976.

24. US DOL Bureau

of Labor Statistics, 1995, reported in The Construction Chart Book,

CPWR, 1998.

25. US DOL Bureau

of Labor Statistics, 1997.